Outline of the Chapter

- Congress vs. Parliament

- Representation and Elections

- Elections in the House and Senate– The Decision to Run, Primaries, and General Elections

- How Congress is Organized

- The Legislative Process

- The Historical Development of Congress in the 20th and 21st Century: From the “Textbook Congress” to the “Hyper-Partisan Congress.”

- Congress in the 21st Century: Polarization, the Legislative Process, Public Relations Wars, and Legislative Entrepreneurs

Learning Objectives

- Explain the significance of the differences between the American Congress and parliamentary systems of government.

- Explain how federal law and Supreme Court decisions shape voting and representation in Congress.

- Explain the factors that contribute to “the incumbency advantage” in Congressional elections.

- Explain the factors that, in addition to the incumbency advantage, shape Congressional elections.

- Explain the role of party leaders and Congressional committees.

- Explain “agenda setting” in Congress using the Wilson “grid.”

- Explain the significance of “pivotal legislators” in Congress.

- Explain the major differences between the “textbook Congress” and the “hyper-partisan” Congress.

I. Congress vs. Parliament↑

Congress, the American bi-cameral legislature consisting of the House and Senate, has had a public relations problem for quite some time. In 2017, President Trump’s approval rating has hovered around 40%; during much of the past decade, the public approval of Congress has hovered around 20%. This is reflected in much scholarly commentary on Congress as well. Congressional scholars Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein published a book entitled The Broken Branch in 2006, when Congress was controlled by Democrats; their subsequent book, written when the House had returned to Republican control, was entitled It is Even Worse than it Looks.1 In these works, Congress was portrayed as a dysfunctional institution in which the individual representatives and Senators were more concerned with their own electoral fate than with public policy, rational deliberation was subordinated to extreme partisanship, and Congressional responsibility within the system of separated powers had been diminished. Not all of these criticisms and observations were particularly new.2 This may suggest that Congress has always been uniquely dysfunctional. Yet there are different ways of interpreting the supposedly dysfunctional character of Congress. It may be the case that Congress, despite its apparent dysfunction and inefficiency, is well-suited to a deeply-divided society, one in which there are fundamental disagreements over what government should do, and how it should go about doing it.

Many criticisms of of the American Congress are based on the assumption that parliamentary forms of government are preferable to the American system, characterized by the separation of powers between the executive and the legislative branch, and a bi-cameral legislative system. The consequences of these institutional differences shape nearly all aspects of politics. One way to think about the differences is to compare them to different forms fighting: parliamentary systems of government are like boxing matches (or, perhaps, mixed martial arts contests), while the American separation of powers system is like a bar fight. In a boxing match, there are clear sides, clear rules, and a clear winner– this is usually, though not always, the pattern reflected in parliamentary politics. The election is the main “fight,” and it produces a government that is clearly in charge, in the sense of being responsible for law and policy.3 In a bar fight, however, no one is quite sure how or when the conflict begins, the sides are often amorphous and possibly changing, it is difficult to tell when or if a victory has been achieved, there is a great deal of screaming and anger, and in the end someone is likely to get sued. That captures the spirit of the American system. It may be well suited for the American people.

That parliamentary governments are in some ways like a boxing match does not mean that the powers of the “victors” in parliamentary governments are unconstrained. Even majority governments must look ahead to the next election; the opposition party provides a constant running commentary and critique that the government must take into account; in what is increasingly a common situation in parliamentary government, different parties must cooperate to form coalition governments. The notion of “responsibility” helps to convey the underlying purposes of parliamentary practice. The phrase “responsible government” has a simple meaning: the executive branch, controlled by the Prime Minister and Cabinet, is responsible to the House of Commons; ministers are selected from the House of Commons, and maintain their position by virtue of the continued support of the House, as shown in their support for major pieces of legislation sponsored by the government. Just as importantly, in a parliamentary system of government, “we the people” know who is responsible for government policy. Federal government spending in Canada is, as of January 4th 2018, the responsibility of the Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Parliamentary systems of government let us know, with admirable clarity, who is responsible for the creation of law, and who is responsible and therefore accountable for implementing public policy. There are some disadvantages to concentrating power in this way, but without a doubt, it makes the lines of responsibility perfectly apparent.

The lines of responsibility are not so clear in American politics. It would not be correct to say, for instance, that President Obama was responsible for the details of the “Affordable Care Act” in the same way that the Conservative government under Prime Minister Harper was responsible for Bill C-51.4 In practice, the roles of Presidents and Prime Ministers are very different. Laws in the United States– any complex or controversial law— are only passed after an extended and often chaotic campaign to mobilize and maintain support. This is because, in the American system, political parties have not developed the power of party discipline, the power to compel individual members of party to support legislative proposals, regardless of their own beliefs or the interests of their constituents. Achieving major policy reforms in the absence of party discipline really is like trying to win a bar fight. There are occasions in which the American system can mimic the cohesiveness and decisiveness of parliamentary regimes. There are instances when parties achieve sweeping electoral victories, establish clear mandates for political change, and enact political change because the party is not divided by serious internal ideological divisions. Those periods are relatively rare. The Constitutional system was designed to make it difficult for any one party to achieve or maintain complete control over national government power, and this institutional bias has been reinforced by the size, diversity, and fractiousness of the American people. We might conclude that this form of government encourages deliberation and cooperation, while inhibiting the power of tyrannical majorities. Yet we might also conclude that the system produces stalemate and gridlock. Both viewpoints are worth considering, as both are partially correct.

The most important difference between Parliament and Congress is that individual legislators in Congress have a considerable degree of power and influence. This distinguishes the American Congress from almost every other legislature in the world, not merely the Canadian House of Commons. Legislators are powerful in the American political system because parties are weak, as American parties have only a limited ability to insure the loyalty of individual legislators. A disciplined party votes as a team, because the party as a whole has the ability to punish defectors by removing them from the party. This weapon does not exist in American politics. Party discipline exists within Congress, to some extent, but it is not the only factor which determines how legislators vote. For instance, there are many reasons why Democratic legislators might wish to follow the lead of their President or of party leaders in Congress.5 There are many reasons why GOP legislators will wish to support Speaker of the House Paul Ryan or Majority Leader of the Senate Mitch McConnell. Should they decide otherwise, however, it is difficult for their leaders to control them.

Why is this the case? Why is the American legislature more chaotic, more individualistic, but also more influential than legislatures in most Parliamentary systems?American parties are often “weak” in the legislative process because the Constitution separates the executive (the President) from the legislature, and establishes specific election dates. The executive does not require the support of the legislature to remain in power, and therefore the incentive for maintaining party discipline in the American political system was never as strong as in Parliamentary system. The separation of the legislative and executive branch is thus the primary institutional cause of the limited party discipline in the American political order. It is true that, during some periods of time, parties exercise significant influence over their members.6 However, the rise of direct primaries, the development of fund-raising and communication tools that enable candidate centered campaigning, and the decline in the power of party leaders in the House and Senate all reduced the ability of parties to control their members. Primaries allow members of Congress to take their political fate into their own hands—and members of Congress spend a great deal of time developing formidable campaign organizations that enable them to do just that. Possessing these resources, individual legislators need not heed the dictates of party leadership—they can consult the wishes and interests of their constituents, or the dictates of their own conscience. As a consequence, party leaders cannot simply present legislative proposals to the legislature and expect perfect agreement and complete support from their party’s members; individual members of Congress insist on playing a major role in developing legislative proposals, in contrast with most parliamentary systems where law- making is dominated by the executive and executive-branch bureaucracies.7

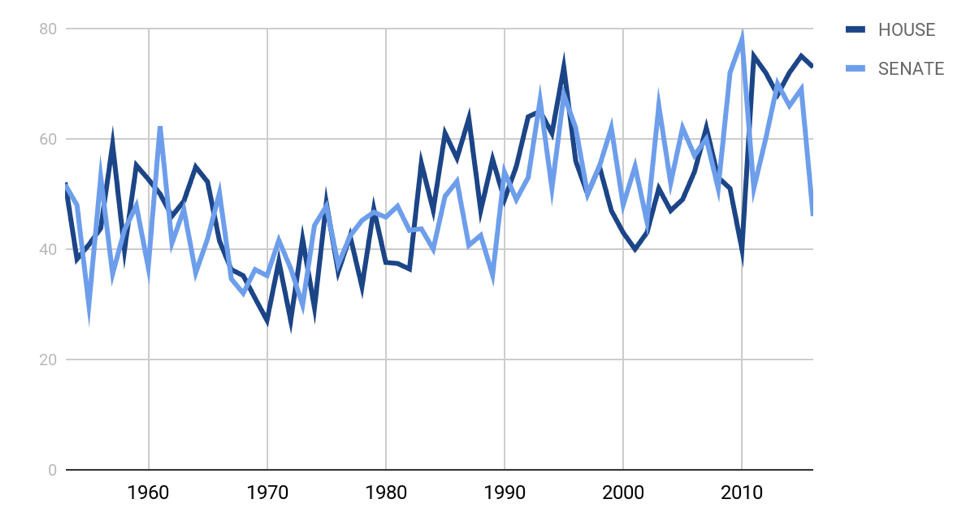

We should note, however, that the degree of party unity in Congress varies over time. This can be seen by looking at “party unity votes” over time (a party unity vote is a vote in which a majority of Democrats vote against a majority of Republicans.)

Figure 5.1: Party Unity Scores in Congress, 1953-20178

Under some circumstances, Congress will behave in a more “parliamentary” fashion, even though party leaders do not have the same ability to influence Senators and House members as do parliamentary leaders Understanding the changing role of parties and party leaders is one of the most important things to consider when trying to understand how Congress operates, and it is one of the most important distinguishing features of the American legislative process. There are other major recurring features of Congress that are just as important– some of which are closely connected to the institutional structure created by the Constitution, some of which have developed as a kind of organic outgrowth of the Constitution.

II. Representation, Voting, and Elections↑

The American Congress and the Canadian Parliament are both representative institutions. But what does it mean for an institution to be “representative”? Representative government is simply a form of government in which one part of society “stands in for” or “re-presents” the public. In the United States and Canada, representation takes place through a democratic process– citizens play a role in selecting individuals who will represent them in Congress or the House of Commons. Though there is some agreement over what it means for a system of representation to be democratic, there is considerable disagreement over what should occur in the process of representation. Some political thinkers have argued that, as far as possible, a legislature should be like a miniature version of society– the demographic characteristics of the individuals who make up the legislature should reflect, in a general way, the demographic characteristics of society as a whole.9 Though some of the founding fathers of the American political system expressed support for the idea of descriptive representation, the American constitution does not attempt to establish it directly. Indirectly, the Constitution creates a certain degree of “descriptive representation” in the House and Senate, for the simple reason that representation is based upon geography. Though there is no way to insure that all groups are represented equally, Congress has always been made up of a geographically diverse group of individuals. Indeed, James Madison thought that this was a crucial benefit of the “extended sphere” of the American republic, as he assumed that economic interests were closely tied to geography. In a society of sufficient geographic size, with a system of representation based upon place (that is, states or congressional districts), there would be no dominant economic interest within Congress. Unsurprisingly, however, Senators and Representatives have tended to come from the relatively well-off segment of society; lawyers are vastly overrepresented amongst the political class as well. In terms of its general make-up, the American Congress does not reflect the full demographic diversity of the nation. Yet over time Congress has become closer to being a “miniature” reflection of society. For instance, in the 115th Congress (the current Congress), there are 45 African members of the House, slightly more than 10% of the total number of seats; African Americans constitute approximately 13% of the populations of the United States as a whole.

It is not clear whether descriptive representation is an essential element of democracy, in that a group can still influence politics even its own members do not hold political office. If a group is part of a political coalition, and if its political power is acknowledged and respected by elected officials and its political preferences taken into account, it may not matter if the group is not represented by one of its own members.10 Effective representation may simply require that the elected official act as an effective delegate for those they represent. Others suggest that effective representation does not even require officials to follow the opinions and preferences of their constituents in all circumstances. According to this trusteeship theory of representation, elected officials can and should exercise their own independent judgment when exercising their public duties, at least under some conditions. Effective representation requires not slavish devotion to public opinion (or the opinion of some sub-set of the public) but rather a certain degree of autonomy for political decision-makers.

The electoral system of the United States reflects the descriptive, delegate, and trusteeship dimensions of representation. One obvious obstacle to descriptive representation in the USA is that, for much of American history, individuals could be denied the vote on the basis of their class, race, ethnicity or gender.11 The original Constitution allowed states to set voting requirements as they saw fit12, and some states restricted the right to vote (or “the franchise”) to property-owning white males. Property restrictions on voting for white males gradually died out in the early part of the nineteenth century, while voting rights for white women were enshrined at the national level in 1920 through the adoption of the nineteenth amendment.13 Voting rights for African Americans took much longer to establish.

Voting rights for African Americans, particularly but not only in the South, would not receive adequate protections from the federal government until the 1960s. It is for this reason that some scholars claim that the United States did not really become a democracy until the final third of the twentieth century. Though the fifteenth amendment had guaranteed African Americans the right to vote, by the end of the nineteenth century the Republican party had more or less abandoned the attempt to insure that the formal right to vote could be exercised in practice. The most important step towards universalizing the right to vote came with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The main purpose of the Voting Rights Act was to insure that African Americans were not prevented from exercising their voting rights. Prior to the 1960s, many Southern states had used various devices to prevent blacks from voting. For instance, fraudulent “literacy tests” were applied to African Americans, but not to whites. As late as the 1960s, in some Southern counties, blacks were given questions about the number of bubbles in a soap bar as part of these tests. The voting rights act empowered the national government to prevent these forms of discrimination.

Supreme Court decisions shaped voting rights in other instances, most notably in relation to the reapportionment revolution initiated in the case of Baker v. Carr (1962). “Apportionment” refers to the ways in which states draw up or “apportion” legislative districts; reapportionment (also called redistricting) usually occurs after the decennial American census, and in theory the redrawing of district lines is meant to take into account changes in population distribution alone. In practice, redistricting can often be used for political purposes– to support a political party, or to reduce to power of particular racial and ethnic groups. In the case of Baker v. Carr, the court ruled that state legislative districts had to have roughly equal numbers of voters– districts could not be “malapportioned” in the legislative branch– and this ruling was extended, through other cases, to Congressional districts as well. This is a good example of how a principle– the principle of equal voting power, summarized inaccurately through the catchphrase “one person, one vote”– became incorporated into Constitutional law even though it has little to do with the Constitution. How do we know that equal voting power is not one of the fundamental principles of the American constitution? The Senate and the Electoral College do not distribute “voting power” in an equal manner. Nevertheless, some judicial innovations become accepted over time, and this is one of those cases.

While courts could equalize Congressional districts, they could not supervise the more subterranean forms of voter discrimination that had emerged in American politics– thus the need for the Voting Rights Act, which allowed the federal government to supervise electoral practices at the state level.14 While the general purpose of the Act was undoubtedly constitutional, the means chosen to implement the policy were somewhat unusual. The most obvious way to implement the policy would be to create the rule– no discrimination in voting– and then allow the Justice Department to prosecute suspected violators. This was done, but more was done as well. The law imposed a “pre-clearance” requirement on many states, which meant that changes in voting regulations had to be “pre-cleared” or approved by the Justice Department. Thus the law seemed to create a new legislative procedure, in which the federal government had a veto over the law-making power of some states. It was definitely cheaper and easier than relying on investigations and prosecutions alone. The Supreme Court shrugged its shoulders, on the grounds that it is acceptable to unofficially amend the Constitution if it is convenient. The argument is bad from a legal perspective, though understandable and maybe even justified from a political perspective.

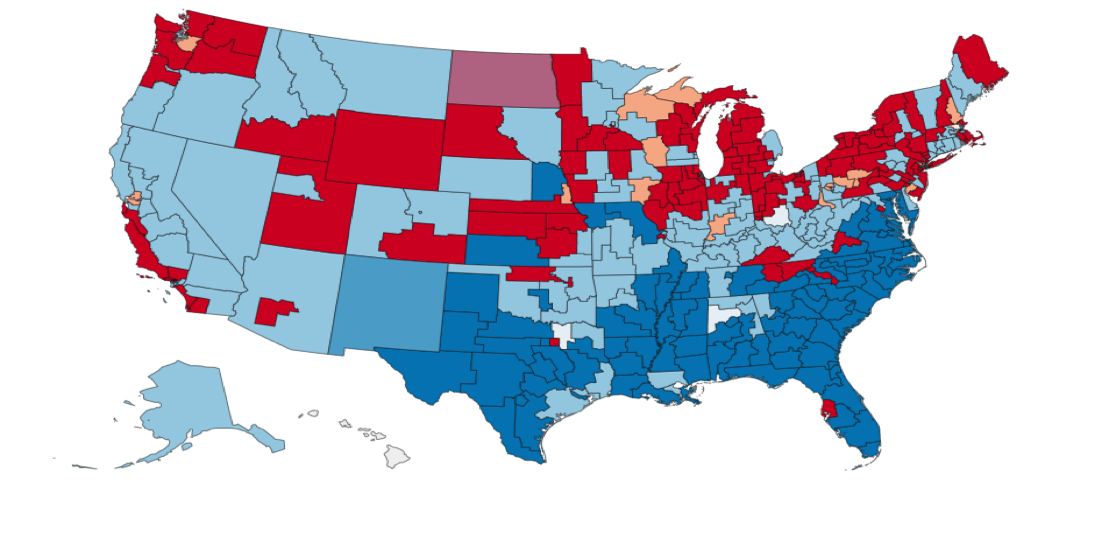

Voter registration for African Americans went up dramatically as a consequence of these changes. (E.g. from 7% voter registration for African Americans in Miss. in 1960 to over 60% by the end of the decade.) The right to vote is not the same thing as the right to elect the candidate of your choice, of course. Over time, the Justice Department became more concerned with the question of voting effectiveness, usually understood in terms of descriptive representation. Through a variety of means, the federal government required states to create “majority-minority” districts in order to prevent the “dilution” of African American votes. The assumption here was that states– at least some states, typically in the south– should be forced to draw district lines so as to group black voters together, so as to increase the likelihood of representation of African American voters by African American officials. The Voting Rights Act, as interpreted by the federal Justice department, interpreted effective representation as descriptive representation.15

From a political perspective, the creation of majority-minority districts raises some interesting issues. Consider this: the Republican party was gaining strength in the South during this period; given this fact, why did it often support the use of “race-based” districting? The answer is that the Republican Party often benefited from having African American voters concentrated in a smaller number of districts, as this made it easier for the Republican party to win in white-majority districts. Majority-minority districting has weakened the Democrats at all political levels in the South, even though it has obviously increased the number of African American legislators.

From a constitutional perspective, the use of race to create majority-minority districts has led to some baffling Supreme Court decisions. The case of Shaw v. Reno from 1994, for instance, did not exactly prohibit race-based districting, but in invalidating a district that was specifically designed to be have a majority of African Americans, the ruling seemed to conclude that race shouldn’t be used “too much.” This case dealt with a district which had a “strange shape;” some parts of the district were no wider than a highway. The problem is that there is no constitutional right to geometrically pleasing congressional districts. Compact and contiguous districts might be important for all kinds of reasons, but they are not required by anything actually written in the Constitution.

Voting rights remain a highly contested issue, as recent Supreme Court decisions such as Shelby County v. Holder demonstrate. This case dealt with the power of “pre-clearance”– the power of the federal Justice Department to approve all changes in voting requirements made by state that had previously engaged in widespread disenfranchisement of racial minorities. The court ruled, in a 5-4 decision, that the practice of pre-clearance could not be applied to only some states, based upon discriminatory practices that had occurred forty years in the past. As a consequence, a larger number of states have been able to change voting rules– abandoning same-day voter registration, for instance, or by tightening voter identification requirements- in ways that could have an impact on the voting rates of blacks and other minorities.

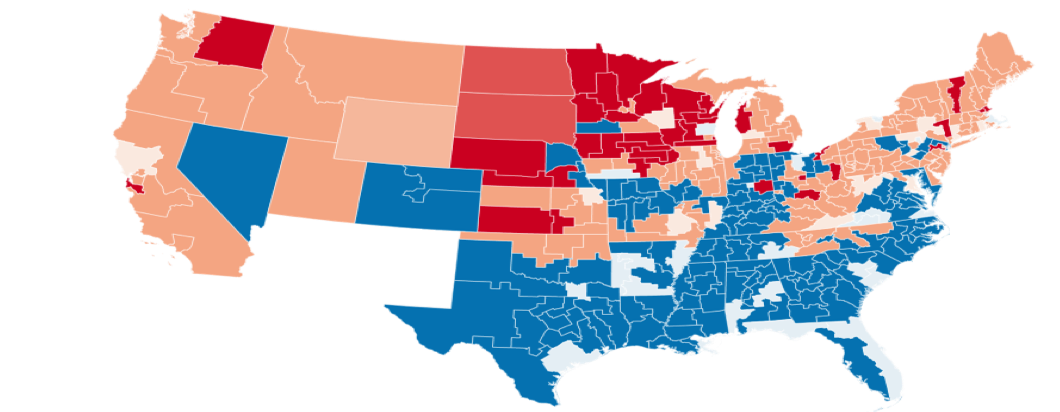

In addition to state-level regulation of the right to vote, state governments are also responsible for drawing legislative districts for the House– the process of “reapportionment.” As discussed above, re-apportionment normally takes place after every official census of the American population (which takes place every ten years.) The 435 congressional districts of the United States then have to be adjusted to take into account shifts in population; states with declining population may have the size of their Congressional delegation reduced, and the district lines may have to be adjusted to make sure that all districts have equal populations. However, as the process of reapportionment is controlled by state legislators, it is not surprising that districts are often drawn with political considerations in mind– this is known as “gerrymandering.” Gerrymandering is simply the process of drawing district lines so as to maximize your own party’s number of seats. This can be done by “cracking” your opponents’ supporters into multiple districts, thereby diluting their impact on elections. It can also be done by “packing” the supporters of the opposing party into as few districts as possible; in those districts, your opponents are likely to win, but many of the votes they receive will have been unnecessary to achieve victory.

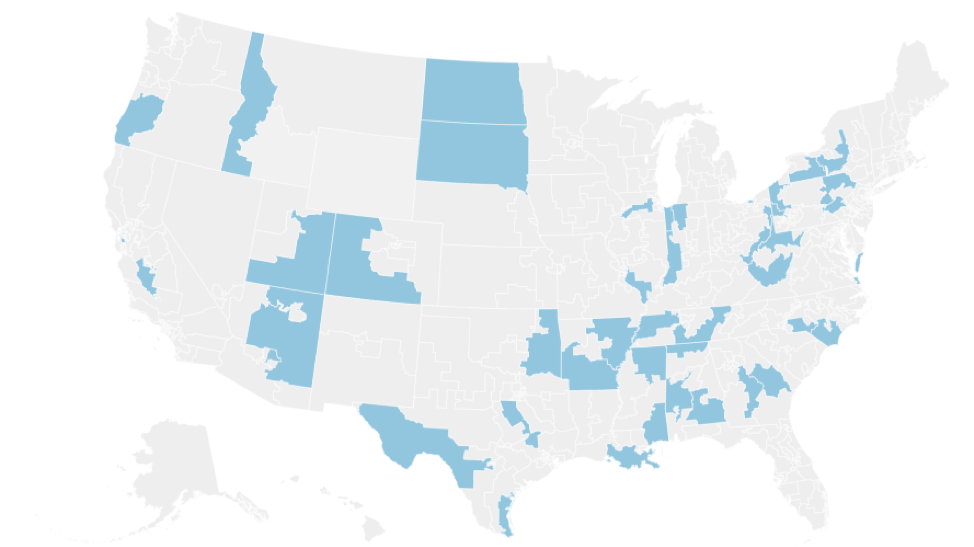

Under current conditions, Republicans benefit from gerrymandering because of their power in state legislatures– in the 2016 election, this means that the GOP received 55% of the seats in the House of Representatives despite receiving only 49% of the vote. The Supreme Court has never ruled that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, yet it has suggested that some kinds of partisan gerrymandering may be unacceptable. Some scholars have suggested that court can use the concept of “the efficiency gap” as a standard to evaluate congressional districting.16 The efficiency gap is determined by calculating the relationship between a party’s “wasted votes” (the number of votes above 50% in districts where it has achieved electoral victories) and the total number of votes. To use this measure as a standard for evaluating the constitutionality of legislative districting, the Supreme Court will have to determine an efficiency gap threshold– perhaps the long-term average, which is around 6%. Almost two dozen states have tried to address the problem of Congressional districting by allowing non-partisan or bi-partisan commissions to manage redistricting.

III. Elections in the House and Senate– The Decision to Run, Primaries, and General Elections↑

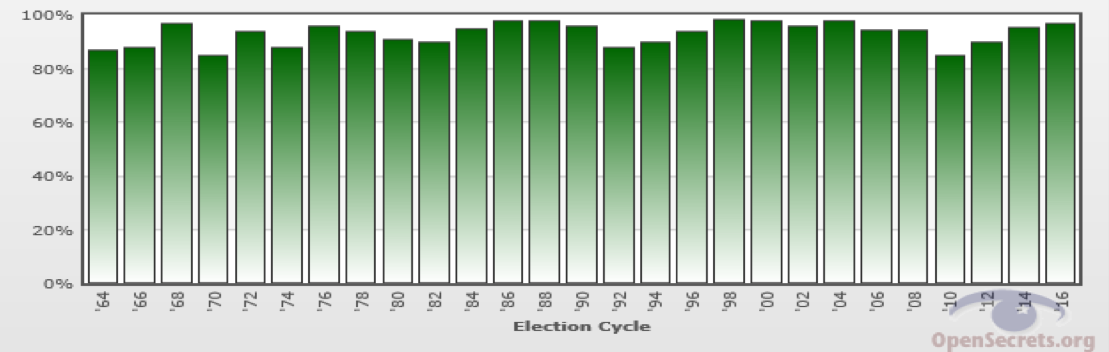

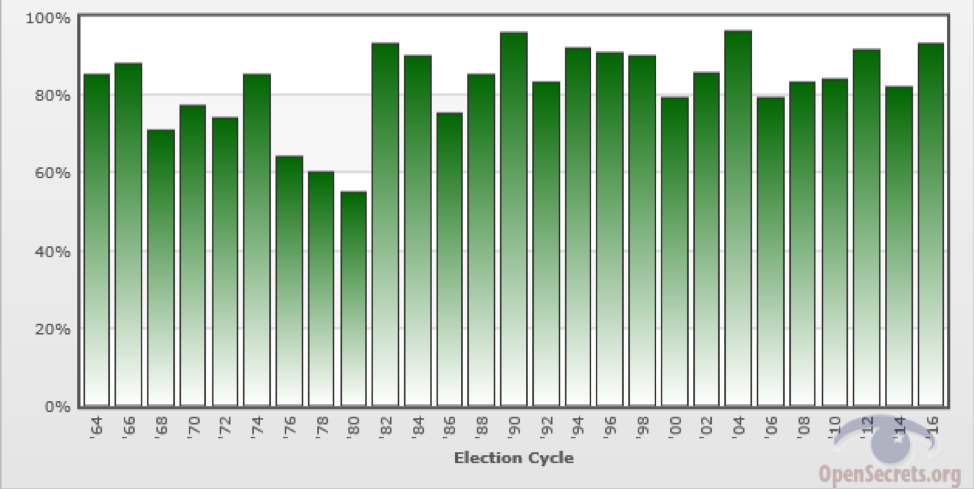

Running for election in the House and Senate is a daunting process. It is costly, time-consuming, and likely to end in failure. The reason for this is rather simple: particularly in regards to the House of Representatives, incumbents (those who already hold office) tend to win re-election. This is known as the incumbency advantage. It is reflected in the high re-election rates for incumbents in House and Senate elections.

Figure 5.2: US House Reelection Rates, 1964-2016

Figure 5.3: US Senate Reelection Rates, 1964-2016

Re-election rates for the Senate are high, though they are not as high as in the House.

The possible causes of the incumbency are easy enough to identify, though it is difficult to determine precisely whether the incumbency advantage results from the advantages of incumbents or the disadvantages of challengers. Perhaps the greatest advantage for those who already hold elected office is that many Congressional districts are not very politically competitive. In the 2016 House election, only 10 races out of 435 had a margin of victory of less than 5%.17 In terms of political beliefs, Americans are more “sorted” by geography than at almost any time in the past. In the 2016 Presidential election, 60% of Americans lived in counties where the margin of victory for either Trump or Clinton was more than 20%.18 In 1976, only 26 percent of the population lived in a “landslide county”.19 Yet even though the results of many House elections are determined well before election, there are years in which major shifts can occur. The most prominent recent example is the mid-term elections of 2010, in which the Democrats lost 63 seats in the House and 53 Democratic incumbents were defeated. Though the country may be more politically sorted than in the past, this does not mean that “battleground” districts have disappeared. In fact, the struggle for control of the House and Senate is much more uncertain in the 21st century than it was for most of the 20th century, even though many incumbents reside in relatively safe districts.

In addition to advantages derived from political geography, incumbents also have personal characteristics that make them difficult to challenge. Incumbents almost always have an advantage in terms of name recognition and fundraising, two very valuable resources in elections.20 Incumbents also have access to the perquisites that come from holding office– resources that they can use to mail material to their constituents, travel budgets that allow them to spend time amongst their constituents, and congressional staff budgets that can further facilitate electoral activities. The ability to communicate and establish familiarity with constituents, famously called the “home-style” of Congressional representatives by the great student of Congress Richard Fenno, has been identified by many scholars as one of the most important sources of the incumbency advantage.21 Technological changes may have contributed to the incumbency advantage as well– according to some scholars, the rise of local television stations in the 1960s and 1970s may have helped Congressional incumbents, as these new media outlets provided additional media coverage to elected representatives.22 These advantages– name recognition, access to media coverage, fundraising, institutional resources of Congressional office– increase the incumbent’s advantages in two main ways. Incumbents are simply able to perform better in the electoral arena, and their resources (particularly their ability to raise vast amounts of money) tend to scare away or intimidate high-quality challengers. Thus even though most Congressional elections are contested, many challengers are political amateurs with little chance of victory.

Given the difficulty and cost of running for election, candidates for House and Senate seats have to be strategic when making a decision to run for office. Often, the best opportunity for new candidates comes when a member of Congress chooses to retire, thus creating an “open seat.” If the state or district leans heavily towards either the Democrats or Republicans, winning the primary will often be more difficult than winning the general election, though this is more likely to be true for House races than for the Senate. It is also the case that opportunities can arise if one of the two parties is encountering a significant decline in public support. While control of Congress was relatively stable between 1932 and 1992, in the previous twenty five years control of the House and Senate has shifted in 1994( the GOP took control of the House and Senate) 2000 (Democrats control the Senate) , 2002 (GOP takes control of the Senate), 2006 (Democrats take control of the House and Senate), 2010 (GOP takes control of the House), and 2014 (GOP takes control of the Senate.)

The decision to run for Congress is to a considerable extent an individual decision; particularly during the primaries, candidates have to rely on their own organizational skills and fundraising acumen to get their campaigns off the ground. Challengers that face long-established incumbents in non-competitive districts or states will often have little more than a bare-bones campaign organization. Competitive seats will usually attract `higher quality`candidates, whether individuals who have their own resources to devote to an election campaign, or individuals who have the experience and connections to raise significant amounts of money.

It is increasingly common for congressional elections, and even congressional primaries, to attract a significant amount of outside spending– spending by independent organizations such as Political Action Committees (PACs), as well as spending by national party committees. Consider, for instance, the case of California district 7, which is located in the North-Central part of the state near Sacramento. In 2014, Democrat Ami Bera won an open seat election in the district, but by a margin of less than 1,500 votes (out of more than 180,000 cast.)23 Unsurprisingly, both parties recognized that the seat would be highly contested in 2016. The Republican candidate, Scott Jones, had been elected sheriff in Sacramento county in 2010, and his campaign emphasized the differences in political views between Jones, Donald Trump, and the conservative “mainstream” of the Republican party ( a matter of necessity in northern California.) Jones, in other words, was a high-quality candidate who had political and electoral experience in the region, and he had a reasonable hope of achieving victory. As a consequence, the candidates raised significant amounts of money for their own campaigns: while the average House campaign raises around $500,000, Bera was able to raise $4,078,146 while his opponent raised $1,354,519. The race was also one of nineteen races in which “outside spending` (more than $8,000,000) was greater than spending by the candidates` campaign organizations (around $5,000,000). Thus while candidates do have to rely on their own fundraising abilities and even personal wealth, political organizations such as PACs and national party committees play a crucial role in many races, particularly closely contested seats.24

National party committees also play a role in recruiting and training candidates. The “Hill Committees” are partisan organizations that are focussed on electing members of the House and Senate; the hill committees are the National Republican Senate Committee, the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee, the National Republican Congressional Committee, and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. These committees are distinct from Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee, which are the formal governing bodies of the national parties which try to coordinate strategy across all levels of local, state, and national politics.

While “Hill committees” attempt to recruit, train, and promote viable candidates, it is crucial to remember that parties have limited ability to select, control, or even influence candidates This is because candidate are selected through primary elections– the most unusual aspect of American electoral politics from a comparative perspective. Try as they might, primary elections obviously make it impossible for party elites to determine who will run for office. The problem is that some candidates who are successful in primary elections are not the most likely to succeed in the general election. This occurs for a very simply reason: voter participation in primary elections is often quite low, and voters in primary elections tend to be more ideologically extreme than other voters aligned with the party.25

This dynamic was on display in the `Tea Party` mid-term election of 2010. The “Tea Party” refers to a largely disorganized social movement that developed over the course the 2009-2010 electoral cycle; there was never any formal Tea Party organization at the national level, and there were no specific requirements for being part of the movement. In general, however, members of the movement were motivated by dissatisfaction with the Republican Party, particularly the GOP’s response to the financial crisis of 2008, the support that the Republican establishment had shown for immigration reform, and the failure to control spending during the George W. Bush era.26 The main short-term tactic of the Tea Party movement was to challenge moderate Republicans in primary elections. From the perspective of the Republican Party establishment, this led to some unfortunate consequences: several Tea Party associated candidates, such as Sharron Angle in Nevada, Christine O’Donnell in Delaware, lost Senate elections that probably could have been won by more moderate candidates. The influence of the Tea Party in these key Senatorial primaries may have cost the Republicans control of the Senate.

While American parties lack the formal ability to control who runs for Congress, there are strategies that they can employ to shape primary elections. Consider the case of the 2014 Congressional mid-terms. The Republican Party was still facing challenges from the inchoate Tea Party movement, but incumbents were more adept at responding to the challenges. Lindsay Graham, Republican Senator from South Carolina, responded to the spectre of a Tea Party challenge in the primary by making highly visible criticisms of the Obama administration, particularly in regards to the Benghazi scandal. Other incumbents were able to fend off primary challenges in a similar manner, though many also benefited from divided opposition. Even so, these were some serious casualties amongst the mainstream Republican party during the primary season. The most startling case was the defeat of House Majority leader Eric Cantor by upstart immigration restrictionist Dave Brat– a result that was anticipated by very few. This is probably the best example of how parties are unable to control their membership; even incumbents who are firmly ensconced in the party’s government hierarchy can suddenly find themselves thrown out of office by the “party in the electorate.”

There are three general categories of factors that shape the outcome of Congressional elections: money and resources, organization and strategy, and background conditions (such as the state of the economy). We begin, as congressional candidate must, with the question of raising money. Congressional elections are not necessarily determined through money alone, but it is nevertheless the case that the ability to raise money is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for electoral victory. Though federal laws (most importantly, the 2002 Bi-Partisan Campaign Finance Act) place many limits on donations to political campaigns, individual candidates can spend an unlimited amount of their own money in pursuit of electoral office. This can often be a futile exercise– in the 2016 electoral cycle, David Trone of Maryland lost the primary for House seat, even though he spent more than $13 million dollars of his own money. In the 2016 general election, some self-financing candidate lost a huge amount of money. Randy Perkins, running In Florida’s 18th district, spent 10 million dollars of his own money in a losing bid to win an open seat, an amount of money that was three times the amount spent by the victor Brian Mast.27 This provides yet another example of the complex relationship between campaign spending and electoral outcomes; just as promotional campaigns cannot always rescue a horrible movie, dumping huge amounts of money into a political campaign cannot rescue a flawed candidate, or overcome the underlying political dynamics of a Congressional district.

While candidates can spend (or waste) as much of their own money as they like on their campaigns, donations by individuals to political campaigns are regulated by campaign finance laws. These donations are often called “hard money” donations (though donations from individuals are not the only type of “hard money.”) Currently, individuals can donate $2500 per election to a candidate. Another major source of hard-money donations are “Political Action Committees” or PACs; these are organizations that raise and spend money in elections. The top spending PACs are dominated by business associations and unions, and they can donate up to $5000 to a candidate per election. Another source of “hard money” direct donations comes from the above-mentioned political party “Hill committees,” as well as from state and local committees.

Table 5.1: “Hard Money” Donations to House Elections, 2016 electoral Cycle (Primaries and General Election)

| Party | # candidates | Individual Donations | PAC Donations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democrats | 908 | $275,105,347 | $151,287,745 |

| Republicans | 1074 | $276,463,148 | $211,319,899 |

Table 5.2: “Hard Money” Donations to House Elections, 2016 electoral Cycle (Primaries and General Election)

| Party | #candidates | Individual Donations | PAC Donations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democrats | 170 | $286,750,451 | $45,139,886 |

| Republicans | 230 | $193,036,593 | $70,597,456 |

Source: https://www.opensecrets.org/overview/index.php?display=T&type=A&cycle=2016

Not all money spent in election campaigns will be spent by the candidates themselves. “Super-PACs” or “independent expenditure only” are organizations that can raise unlimited amounts of money and spend unlimited amounts of money advocating for particular candidates, criticizing particular candidates, or addressing particular causes. In contrast with ordinary PACs, the “super” versions cannot actually donate to particular candidates, and in addition, they cannot coordinate their campaign-related activities with candidate committees. Famously, or infamously, the Supreme Court has played a major role in lifting restrictions on Super -PAC fundraising and spending. In the case of Citizens’ United v. United States, the court ruled in a narrow decision that the primary justification for campaign finance laws was to prevent corruption; therefore, while this would justify limits on direct donations to candidates, it does not justify limits on other types of political communication. If the independent expenditure related provisions of the BCRA had been allowed to stand, the government would have had the power to regulate any film, book, newspaper, or advertisement created by any corporation. Some claimed that this conferred rights on corporations, rights which they do not possess because they are not individual persons; this is correct, however, it isn’t clear why groups of people should be denied rights merely because because they choose to take advantage of the corporate form of organization.

There are two other general kinds of organizations that are also engaged in Congressional election spending spree, both named after the relevant sections of the U.S. Tax Code: Section 527 organizations and Section 501(c)4 organizations. Section 527 organizations, unlike Super-PACs, cannot advocate on behalf or against particular parties or candidates. Section 501(c)4s are tax-exempt “social welfare” organizations that can spend money on political causes such as issue advocacy, as long as political advocacy is not the primary purpose of the organization; these organizations are sometimes referred to as “dark money” organizations, because they are not required to reveal information about their donors. The National Rifle Association, Planned Parenthood, and the Sierra Club are examples of well-known 501(c)4 organizations.

What is the ultimate impact of all of this money– whether the highly regulated “hard money” that goes directly to candidate campaign committees, or the largely unregulated “soft money” spent in the electoral cycle by Super-PACs, 527s, and 501(c)4 organizations? If we restrict ourselves to the electoral process, it is difficult to know the exact impact of campaign spending, whether in the hard or soft form. As noted above, and as demonstrated by the Presidential election of 2016, a candidate’s campaign can have a massive fundraising advantage and yet still lose the election. Beyond that, it is difficult to give a precise answer to the effect of money in the electoral process. It is, however, rather easy to explain why it is so difficult to assess the impact of money in Congressional elections. Incumbents tend to win re-election, and they also tend to raise more money than challengers; does the advantage in campaign spending allow the incumbents to win, or does the fact that they are likely win reelection allow them to raise additional money? Incumbents have many advantages that have little to with campaign spending– they may come a district or state that favours their party, they may have proven themselves to be effective advocates for the interests of their constituents, they may have established name-recognition through years or even decades of political service. When challengers achieve victory, it is similarly to difficult to isolate the independent effects of money on electoral outcomes, because the quality of the challenge is not independent of the amount of money raised by the challenger. The effect of money on elections, in other words, depends upon a host of factors. 28 Even if we continue to think that money determines electoral outcomes, we should be consoled by the fact that, in general, the main political parties and their interest groups allies. are roughly equal in their ability to raise money. This is not to suggest that money does not influence American politics, but it is to suggest that the electoral process is not completely distorted by campaign spending.

IV. How Congress is Organized↑

Congress consists of 535 legislators– 435 members of the House, and 100 Senators. While these legislators are largely responsible for their own electoral fortunes, and even though they have far more independence than legislators in parliamentary forms of government, it is still necessary for Congress to organize itself if it wishes to accomplish anything. There are three major dimensions of Congressional organization– the constitutional dimension (the separation of the House and the Senate as separate legislative chambers), partisan organization (which is primarily about organizing parties within the House and Senate in order to set a legislative agenda and pass bills), committee organization (which is primarily about dividing up policy authority into specialized sub-units, thereby allowing the legislative branch to benefit from the division of labour, and allowing individual legislators to develop policy expertise. )

a) Bi-Cameralism: The House vs. The Senate

The most striking feature of Congress is that it is a bi-cameral legislature, with an “upper house” that in no way sees itself as being less legitimate than the lower house (in contrast with the Canadian Senate, of course.)29 The purpose of the Senate, as James Madison elaborates in Federalist Paper #62, is to make it difficult to create law. If you have two legislative bodies who must come to agreement before a law is passed, and if those legislative bodies are selected based upon different principles (representation by population versus representation by state), and if the time-frame of elections differs (every two years versus staggered six year terms) then there are likely to be important differences between the interests and perspective of the two bodies. It will be difficult for them to come to agreement, particularly in regards to contentious issues. In this way the Constitution places obstacles in the path of the majority, though not insuperable obstacles. 30

Consider the shift in public opinion that occurred in 2010. Through a combination of economic stagnation, depressed voter turnout for the Democrats, and the mobilization of the Tea Party which shook up the GOP establishment and energized conservative voters, there was a massive shift in seats in the House of Representatives: the GOP won 63 seats, the largest shift in House elections since 1948. Yet despite this massive shift, there was not even a complete shift of power within Congress; despite winning six additional seats, which presumably reflects at least some change in public opinion, the GOP could not take control of the Senate. The Constitution makes it difficult for short term changes in public opinion to change the balance of power in Washington, and the Senate plays a key role in this dynamic. Taking over the Senate is a long-term process. Only 1/3 of the Senate comes up for election every two years. When only 1/3 of the Senate seats are up for grabs, it is obviously difficult to translate short term shifts in public sentiment to shifts in control of the Senate.

The structure of elections can lead to tension between the House and Senate. What about the differences in constituency? The Senate is apportioned by state; every state, no matter how small and weird, is given two Senators; the House of Representatives is based upon representation by population. To what extent does regional representation affect legislative politics in the USA? On the one hand, the “small state” bias of the Senate works in favour of the Republican Party31; smaller states are typically more rural states, and while this may have helped some Democrats during the days of William Jennings Bryan and prairie populism, today rural voters tend to support the Republican Party. Consider as well that the smallest 25 states have approximately 58 million residents out of a total population of 318 million; theoretically, therefore, Senators representing a small fraction of the nation could thwart the wishes of national majorities (though one should note that the interests and politics of small states are far from uniform—it is very difficult to think of a contemporary issue that would unite small states against large states, other than a proposal to eliminate equal state representation in the Senate.) However, it is common for bills to be voted down by Senate majorities that do not represent popular majorities—for example, the immigration reform bill that was voted down in the Senate in 2007.32

Not surprisingly, political scientists are in some disagreement over the question of whether the Senate gives a decisive political advantage to the Republican Party. Yale political scientist David Mayhew argues that the GOP’s advantage is small, and is offset in the contemporary era by the presence of a not insignificant number of small, Democrat leaning states such as Hawaii.33 However, other scholars suggest that the interests of small states often play a disproportionate role; for instance, some have speculated that the Senate has opposed climate change initiatives because low population rural states often rely on fossil fuels more than urbanized states.34 Just as the differing modes of election can produce tensions between the House and the Senate, the differing constituencies of the House and the Senate can be a source of disagreement and gridlock.

b) Party Organization, Party Leaders, and Caucuses in Congress

Parties play a role in Congress that is in some ways the same as parties in parliamentary regimes– the parties are “teams” of like-minded individuals who ban together in order to select leaders, set the legislative agenda, and manage the legislative process. The most obvious difference between parties in the American Congress and parties in parliamentary regimes like Canada is that Congressional parties do not actually select the executive (except under what have proven to be very unusual circumstances. Congressional parties do select leadership positions within Congress, however. Whether through the Republican conference or the Democratic caucus (the names that the parties give to their collective members in Congress), the majority party in the House and Senate elect candidates for the two most important position in Congress: the Speaker of the House, and the majority leader of the Senate. The House majority also selects a House Majority leader; the minority party selects a Senate Minority Leader and a House Minority; both parties in both chambers also select “party whips” (individuals whose main responsibility is to help party leaders maintain the votes of their own members.) The jobs of legislative leaders in the U.S. Congress is usually much more complicated than that of their parliamentary counterparts. Parties exist to promote cooperation, but the Speaker of the House and the Majority leader of the Senate have no real way to discipline recalcitrant legislators; successful leaders in the American Congress have to be expert bargainers and deal-makers, in order to forge compromise within their own parties and, often enough, with opposing parties or opposing Presidents. In comparison with parliamentary leaders, Congressional party leaders have few tools to discipline their members. The limits of party discipline in Congress, and the limited power of Congressional leaders, is actually the source of Congressional power; party discipline in parliamentary regimes insures that Prime Ministers, cabinet, and the bureaucracy dominate the policy making process.

Party leaders in the U.S. House and Senate includes play a key role in making initial committee assignments (see below) and in setting the legislative agenda. The committee assignment power has changed in significant ways over the years, but the main concern of party leaders is to insure that they have solid majorities on the major committees. A secondary, but still important, concerns is to assign individual legislators to committees where they will be able to make the most significant contribution. This usually means assigning people to committees that are of particular concern to their constituents. Setting the legislative agenda is not something that Congress controls entirely; in a formal sense, however, the leaders of the House and Senate bear responsibility for assigning bills to committees, establishing the legislative calendar (the schedule which establishes which bills will be taken up before the full House and Senate), and, in general, overseeing the law-making process.

In addition to party leaders, Congress is also organized into caucuses– groups, some of which are bi-partisan, which are united based upon shared ideology, shared interests, or shared identity. For instance, the Congressional Black Caucus consists of African American legislators, and has included members from both parties. Other congressional caucuses are organized around ideology– such as the conservative Republican Study Committee, or the Blue Dog Coalition, a caucus which consists of moderate Democrats from conservative leaning regions of the country. While not as crucial as party leaders, caucus organizations can play a role in helping to identify public problems, advance policy ideas, and alert party leaders to the concerns of the party rank and file.

c) Congressional Committees

Many aspects of Congress are established by the Constitutionalism; bi-cameralism and the Presidential veto are two examples of institutional features established by the Constitution that shape the and cannot be easily changed. legislative process. Yet the internal operation of Congress is not determined by the Constitution, at least not directly. The organization of parties, and the process of analyzing and reviewing legislative proposals, are not determined by the Constitution itself. The Constitution sets certain rules in place– for instance, the rule that a bill only becomes a law when it is passed in identical form by the House and Senate. Yet Congress itself determines the structure of the legislative process. The most important institutional feature of this process is the committee system.

Committees are sub-groups within Congress that review and develop legislative proposals. Their primary role in the legislative process is to act as gate-keepers of the legislative process– that is, they decide which proposals will be taken seriously, and which will be thrown under the bus. The basic purpose of congressional committees35 is to prepare bills for consideration in the House and the Senate, something which could not be accomplished without the division of labour. In order to prepare bills for consideration and voting in the House and Senate, committees hold “hearings”36 and “mark-up” bills to craft the specific language used in the bill.. Committees also play an important “gatekeeping” function—they determine what kinds of issues will receive serious attention, and they determine which issues can be ignored (though we should note that committee gatekeepers have to be attentive to the wishes of party leaders and the President.)

Table 5.3: House Committees

| Committee Name | Jurisdiction (examples)a |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | Agriculture (including farm credit, commodity exchanges, rural development), SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) |

| Appropriations | Expenditure bills |

| Budget | |

| Education and the Workforce | |

| Energy and Commerce | |

| Ethics | |

| Financial Services | |

| Foreign Affairs | |

| Homeland Security | |

| Intelligence | |

| Judiciary | |

| Natural Resources | |

| Oversight and Government Reform | |

| Rules | |

| Science, Space and Technology | |

| Small Business | |

| Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| Veterans Affairs | |

| Ways and Means |

There are several committees which are particularly noteworthy. The House Rules Committee determines the parameters of debate within the House; while the Rules Committee was once a major thorn in the side of Congressional majorities37, since the 1960s it has been carefully controlled by party leaders.38 The House Appropriations Committee has jurisdiction over annual appropriation bills—that is, bills that deal with discretionary government spending, as opposed to “entitlement” spending such as Social Security; this committee is responsible for reviewing and considering the budget requests of the President and executive branch agencies, and is thus particularly important.39 The House Committee on Ways and Means has jurisdiction over tax bills, as well as social programs such as Social Security and Medicare.40 The House Budget Committee exists to oversee the budget reconciliation process.41

One of the most important dynamics in Congress is the relative balance of power between committees and parties, particularly party leaders. Committees are not necessarily representative of Congress in an ideological sense, though the balance of votes on committees reflects the official partisan balance of power. Congress as a whole delegates power and responsibility to committees, but it is possible for the interests of the committee to diverge from the interests of Congress as a whole.

There are three basic theories about the role of committees– all of which are true to some extent, though not at the same time and in the same way. The “Committee Autonomy- Distributional Hypothesis” is that committees control outcomes relevant to their constituencies, jurisdiction, and policy interests; in practice, this makes committee politics the locus of institutionalized log-rolling and parochialism. In other words, the decisions made by committees might not reflect the decisions that majorities in the House and Senate would make, if there was no “division of labour” in the legislative process and all members of the House and Senate were able to decide upon all issues. One example of this “principal-agent”42 problem is the House Agriculture Committee and its relationship to the Republican Party. The Republican Party is, in theory, a “neo-liberal” party which opposes government subsidies for business; the members who sit on the House Agricultural committee, however, are motivated not merely by ideology but also by their interest in being re-elected by their rural constituents. Regardless of the neo-liberal ideology of the party as a whole, the Republican members of the House Agricultural committee are usually reluctant to give up on ethanol subsidies, sugar subsidies, and other policies that direct federal money to struggling agri-business conglomerates.43

But committee members are not always captured by the interests that they represent. According to the informational hypothesis, the committees allow members of Congress to divide their labour and develop specialized expertise; according to the “party dominance” theory, committees are organized to advance the interests of the majority party, and thus the votes and decisions of committee members usually reflect what party majorities prefer, and not just the short term interests of the committee’s constituents. As we will see, however, committees have various tools that allow them to frustrate the will of the majority—though these tools become less significant during periods when the parties are united by shared beliefs or ideologies.

The role of committees is a good example of a “centrifugal forces” in American Congressional politics. Committees can limit the power of “the center” (in this case, party leaders in Congress, backed by partisan majorities) , in contrast with parliamentary politics, where power lies at the centre, in the cabinet and the Prime Minister. To understand Congress, we must understand the following things: bi-cameralism and the institutional differences between the House and Senate; the potential tensions between Congressional majorities and committees; the inter-relationship between Parties, Party Leaders, and Individual legislators; and the relationship between Congress and the Presidency in the legislative process. Encompassing all of these relationships is the interaction between public opinion and the legislative process, a relationship which is much more dynamic in the American system as opposed to parliamentary systems. The American legislative process, under contemporary conditions, has a tendency to spill over into the public arena. We must understand the interests and ideas that motivate legislators, and the institutions that structure how they pursue their interests and implement their ideas.

V. The Legislative Process↑

a) Agenda Setting

Now that we have considered the basic institutional structure of the legislative process, we can consider what the process looks like in practice. The first stage in the legislative process is the “proposal” or “agenda setting” stage, leading to the “introduction” of a bill. While a member of the House has to formally introduce a bill, there are no specific rules about where policy proposals can come from.44 There are standard norms for determining what proposals will be taken seriously, however. At any given moment in time, there are an almost inexhaustible number of possible policy issues that Congress might choose to address; to set the agenda, then, is simply to set priorities, to make decisions about what issues will be the focus of Congressional action, and what issues will be ignored. Almost always, the President’s proposals will be the primary influence one the Congressional agenda. In addition, party organizations within Congress– the Republican Conference and the Democratic Caucus– will be the source of legislative proposals; one example of this is Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America,” from 1994. Yet agenda-setting cannot be understood if we only look at actors within the national government.

Agenda-setting in Congress occurs through a combination of disparate social forces and individual action. In some instances, the agenda is set by literally decades of “ideological entrepreneurship”: a process of identifying policy problems, articulating possible solutions, and disseminating those ideas through the broader public sphere.45 The proposals and platforms of Presidents and political parties are thus only the tip of the agenda-setting iceberg. Mass media can play a role in setting the policy agenda by drawing attention to certain kinds of problems, or framing problems in particular ways. Policy entrepreneurs– individuals, interest groups, or even broader social movements– can play a similar role in identifying public policy problems and suggesting policy solutions. Finally crises of various kinds, whether natural, economic, or political, can re-shape the Congressional agenda in unexpected ways.

Mass media, policy entrepreneurs, and crises often work together simultaneously in setting the Congressional legislative agenda. Consider, for in the instance, the response of Congress to the financial crisis of 2008. Much like the Great Depression of the 1930s, the causes of the financial crisis are numerous, complicated, and poorly understood, at least in the sense that highly qualified economic policy experts have come to differing conclusions over the precise causes of the financial crisis. Mass media played a role in shaping public consciousness of the causes of the financial crisis by highlighting a fairly simple and straightforward narrative about the causes of the crisis: the crisis was caused by excessive speculation by financial institutions, and further crises can be prevented by subjecting financial institutions to stricter regulation.46 While the public may have been more amenable to the idea of strict financial regulation after experiencing the effects of the financial crisis and media interpretations of the crisis, this does not mean that “the public” has any particular ideas about what stricter regulation might mean in practice. This is where policy entrepreneurs play a role, in this case, by developing specific ideas about how to frame legislation. For instance, prior to becoming Senator, Elizabeth Warren had developed the idea that financial products should be subjected to government evaluation and regulation, similar to the ways in which new pharmaceuticals are evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Warren’s ideas became basis for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, one of the most significant and most controversial elements of the Dodd-Frank financial reforms. 47

Legislative proposals typically originate in three different ways: from the Presidency and the Executive, from Congressional party leadership, and from individual legislative entrepreneurs within Congress. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 is a good example of a legislative proposal that began within the executive branch. President Obama had raised the issue of financial reform during his Presidential primary campaign, well-before the financial crisis had occurred. In the aftermath of the financial crash, Obama administration officials, along with a variety of academic experts, laid the groundwork for the initial legislative proposal that would become the Dodd-Frank bill.48 In other circumstances, the legislative agenda is set by the majority party, as in the aftermath of the 1994 election when the Newt Gingrich-led Congressional Republicans attempted to implement their “Contract with America.”49 Individual legislators also play a key role in establishing the legislative agenda. Whether as a consequence of their own individual policy ideas, or as a consequence of their relationship with influential interest groups, individual legislators in the American Congress often play a crucial role in developing policy ideas and pushing political issues onto the Congressional agenda.50 One should also note that Presidents, the executive branch, Congressional leaders, and individual legislative entrepreneurs often work together simultaneously to establish a legislative agenda.

Looked at more broadly, setting the legislative agenda is a process that encompasses both government officials as well as interest groups and public opinion. Part of the great difficulty of understanding this process is that “agenda-setting” encompasses both issues that draw Congress’ attention, but also issues that fail to draw Congress– what might be called “negative agenda setting.” While there are many different ways of looking at the agenda setting process, James Q. Wilson’s theory of policy-making, based upon the ways in which different policies impose costs and benefits is a useful starting point. According to Wilson, Congressional policies impose costs that are concentrated on particular set of individuals or groups, or they impose costs that are diffused through society as a whole. Benefits are distributed in a similar way. This yields four theoretically distinct types of policy areas, each of which creates a distinct kind of politics; they are presented in the “Wilson grid” below:

Table 5.4: The Wilson Grid: Public Policy and the Distribution of Costs and Benefits

| BenefitsCosts | Concentrated | Widely Distributed |

|---|---|---|

| Concentrated | Interest Group Politics | Client Politics |

| Widely Distributed | Entrepreneurial Politics | Majoritarian Politics |

Interest Group Politics: This form of politics tends to occur when the benefits and costs of a policy fall upon (relatively) small sectors of society. The usual (and most important) example of this category of policy-making are laws that affect labor rights and labor organization; the agenda in this area of policy-making will be set by the relative power of union and business organizations (which will depend upon the strength of their supporters and allies within Congress.)

Majoritarian Politics: Majoritarian policies impose costs and distribute benefits to society as a whole (or to large swathes of society.) The most important example of this type of policy-making is income tax policy, though as we will see tax policy can also take the form of “client politics.”

Client Politics: Client politics occurs when the benefits of a policy affect a relatively concentrated group, while the cost are imposed on society as a whole. The best example of this kind of policy-making are policies that direct subsidies to particular groups e.g. farmers, weapons manufacturers, etc.

Entrepreneurial Politics: Some of the most contentious forms of policy-making in Congress occurs when legislators attempt to create laws that provide public benefits while imposing costs on relatively concentrated (and thus, easier to organize) constituencies. Safety regulation, drug regulation, and environmental regulation all fall into this category. This type of policy-making is called “entrepreneurial” because overcoming the resistance of entrenched interests usually requires the leadership of “policy entrepreneurs” insides and outside of Congress: highly motivated and skilled individuals who are able to promote policy ideas even in the face of interest group resistance.

Banking and finance reform during the Obama administration illustrate some of the problems and difficulties “entrepreneurial politics” in Congress; it also shows how the same policy domain can, depending upon what Congress is trying to do, fall into different categories. The public, arguably, has an interest in a stable financial system, one in which public money is not spent to save private investment banks and insurers; those same financial institutions want to benefit from limited regulation during good times, and they want governments to provide support for them during financial crises. Imposing major regulations on the financial industry usually requires a precipitating event or series of events, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s or the financial crisis of 2008. In the aftermath of those events, policy entrepreneurs within Congress were able to overcome, at least in part, the power of the “financial-industrial complex” to stymie reform. At the very least, supporters of financial reform (such as Massachusetts politicians Barney Frank and Elizabeth Warren) were able to get the issue on the Congressional agenda.

b)The Legislative Process in the House and Senate: Committees

Once the agenda is established, party leaders in the House and Senate start sending the work out to relevant committees; this is the “referral” process. The role of the Speaker of the House is very significant here; they monitor and guide what is happening within the committees, in order to help insure that the legislation will be acceptable to their party as a whole. Leadership in the House becomes even more significant when you are dealing with large, complex bills– sometimes called “omnibus” bills– that do not even deal with related issues; in regards to these bills, the Speaker plays the role of coordinator between committees. The ultimate goal at the committee stage is to create legislation that will be acceptable to most party members, pass the House, and not undermine the party’s electoral fortunes. This is not always easy.

Parties in the legislature do not necessarily have to rely on committees in order to develop legislative proposals. Between the 1960s and the 1980s, 7% of major pieces of legislation “bypassed” the committee process in the Senate; between 2009 and 2014, an average of 52% of major legislative proposals were not considered in committees.51 This is probably a sign of the increased ideological homogeneity in Congress. In the past, members of Congress were more jealous about the prerogatives of the committees, because they assumed—often correctly—that the perspectives of committee members might well differ from the perspective of their parties as a whole. In the first systematic study of committee politics, conducted in the 1960s, the political scientist Richard Fenno emphasized that congressional committees were to some degree independent of their political parties; the interests of individual members of Congress (in getting re-elected, in achieving personal influence and power, and creating good public policy) were often served by maintaining committee autonomy (the ability of committees to dominate the law-making process.) Yet as political parties have become more polarized, and as electoral outcomes have become more uncertain, partisan identity has become more significant than committee membership; under these circumstances, it is more common for individual members to accept a reduced role for committees, at least under some circumstances.

The House has the ability to bring committee deliberation (or committee stalling) to an end by using a discharge petition, which require signatures from a majority in the House and can be proposed by any member. Discharge petitions attempt to end the committee stage of the legislative process, particularly if the committee is hostile or ambivalent. They are, however, relatively rare: between 1931 and 2010 there were 628 discharge petitions, and only 31 of these petitions actually led to a discharge (this is probably because the threat of discharge is effective in getting committees to get their act together.)52

There are many reasons why leaders and members might want to pressure committees, or might want to bypass them altogether. In some cases, time pressure makes it necessary to move to consideration on the floor as quickly as possible; this was the case regarding TARP legislation in the fall of 2008. In other cases, the legislation may have already been considered in previous sessions of Congress, or the majority may want to pass a law very quickly without attracting public attention.

Party leaders often have to play a role in reconciling complex bills that have been parcelled out to multiple committees—this is the “post-committee adjustment” stage which precedes consideration on the floor. In addition to addressing discrepancies between bills that have been referred to multiple committees, party leaders may wish to change parts of the bill in order to increase support, whether from members of Congress or the President.

Within political science, there are two main theories which attempt to explain how committees conduct their work. According to the “Informational Model,” —committees simply allow members of Congress to specialize, thereby reducing uncertainty and improving the quality of legislative output. By way of contrast, the “gains from trade” model suggests that committees consist of “preference outliers” who pursue policies that depart from the preferences of the majority. Committees engage in a collective “logrolling” process, in which the special deals of one committee are accepted by other members, who have their own special deals and arrangements that they hope will sustained by the legislature. Both theories are partially true.53 Looking at the committee process allows us to understand how, even in an era of partisan polarization, the legislative process requires Congressional leaders to balance the interests of competing “factions,” at least within the committee process.

The “informational model” of Congress suggests that the main purpose of congressional committees is to allow individual members to develop relevant expertise. One of the troubling themes that emerges in detailed investigations of law-making, such as An Act of Congress by Robert Kaiser, is that congressional committees are, in practice, composed of individuals with very limited expertise. Even those who have been longstanding members of standing committees have very imperfect understandings of key policy issues. The usual complaint of representatives and Senators is that the demands of constituency service and fundraising make it difficult for them to acquire knowledge. More troubling is the possibility that no amount of time and effort would enable legislators to fully understand all of the complexities of issues such as financial regulation and health care politics.

Robert Kaiser’s narrative about the passage of the Dodd-Frank bill in 2009-2010 suggests that there was no real “informational advantage” amongst members of the committee as a whole. In practice, only a relatively small group of legislators and Congressional aides have enough expertise to really understand the relevant policy issues. Even though members of Congress played a role in developing the bill, much of the substance of the bill has already been developed by officials from the executive branch (in the case of the Dodd-Frank bill, the executive branch officials were mostly from the Treasury department). In many cases, the substance of the legislation was developed by individuals with unusually close connections to the financial industry itself. Deference to executive branch officials is more prominent in committee work, as opposed to rabid partisan squabbling. There is thus a kind of convergence between the parliamentary-executive dominated model of law-making, and the American Congressional model, especially when we are dealing with highly complex pieces of legislation. This raises all kinds of interesting questions: are (unaccountable officials) acting on the basis of expertise, or on the basis of their interests? To what extent are aides/experts influenced by connections to the world of high finance? Though it is only one example, the role played by the House Financial Services Committee in creating the Dodd-Frank financial regulations suggest some of the limits of the “informational model.” There are clearly individual representatives who develop significant policy-making expertise, but they may be an exception, not the norm. 54