Outline of the Chapter

- Introduction: The American Constitution and American Politics

- What is a Constitution?

- From the Declaration of Independence to the Articles of Confederation

- The Constitutional Convention of 1787: Liberalism. Republicanism, and the Problem of Slavery

- Defending the New Constitution: The Federalist Papers

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the Declaration of Independence attempts to justify the American revolution.

- Explain the meaning of the term “constitution,” with reference to the concepts of policy agency, policy authority, and policy process.

- Explain how the major features of the first American constitution—the Articles of Confederation—led to “constitutional failure” in the 1780s.

- Explain how both ideas and interests influenced the framers of the Constitution of 1787.

- Explain “the great compromise” that was the basis of the Constitution of 1787, and how this created a policy process that was “inefficient by design.”

- Explain the concept of “faction,” and explain how the Constitution of 1787 was meant to solve “the mischiefs of faction.”

I. Introduction↑

The American Constitution is probably the single most important influence on American politics. It establishes the “rules of the game” for government, and like all other games, you cannot understand what is going on – and you certainly cannot play the game—unless you pay some attention to the rules. If you want to understand the game of basketball, for instance, you have to begin by considering the rules regarding dribbling, shooting, the height of the basket, defence, and so on. A different set of rules would create a very different game.

Just how important are political institutions in shaping the political life of nations? Undoubtedly, there are aspects of American politics that would have shaped the nation’s history even if the United States had adopted a parliamentary system of government. The role of the frontier and western expansion, the issues of race and sectionalism1, the prominence of religion, the challenges of technological, industrial, and international change, are some of the most prominent features of the USA that were not created by the Constitution, and these things would have influenced American politics even if they had adopted a radically different constitutional system. Nevertheless, there are common sense reasons to think that the structure of the American constitution has shaped American politics, just as the rules of basketball have made it a game well suited for the abnormally tall.

The Constitution created a form of government which is inefficient at making law. Why would we want anything to be inefficient, particularly a set of political institutions? There is a simple reason for this: in a democracy, a political system is “efficient” if it quickly implements the will of the majority, and that is not self-evidently good. Inefficiencies, understood as constraints upon simple majoritarianism, were built into almost every aspect of the American legislative process (though not every aspect of the American national government) in order to limit the power of the majority. When we hear politicians or journalists grumble about the inefficiency of American politics, and when we hear Americans speak contemptuously about the evils of “gridlock” in Congress, we must remember that these supposed defects of the American political process are not caused by moral failure on the part of politicians and their supporters. “Gridlock,” “legislative inefficiency,” “political hostage taking,” or politicians failing to respond quickly to majority will, are entirely unexceptional elements of the American political order. The inefficiency of American politics exists by design, not by accident.

Consider the conflicts over immigration reform that the United States is currently experiencing. “Immigration reform” in the USA focuses not on the question of “how many immigrants should the USA accept?” but rather on the question of whether or how to enforce current immigration laws. Leaders and activists associated with the Democratic Party tend to support amnesty for illegal immigrants who live and work within the United States. The Republican Party is home to many voters who are opposed to amnesty and illegal immigration. At the same time, many within the GOP leadership, and many key GOP leaning interest groups think that the future of the party and the country depends upon expanding the numbers of immigrants who will accept low wages for unpleasant work. The current policy status quo is not really acceptable to any of these factions, yet reform has proven incredibly elusive and contentious. One could argue that, in circumstances of this kind, the “gridlock” of the American political system is not a “bug,” but rather a “feature.” Major policy changes can occur in parliamentary systems of government, based upon slim legislative majorities and relatively uncertain public opinion. The American constitutional system is designed to make it incredibly difficult for legislative majorities to form, particularly when public opinion is divided. This might be the most fundamental difference between the American constitutional order and parliamentary systems: in parliamentary systems, a relatively slim majority amongst voters can translate into authoritative legislative majorities, whereas in the American system, a party can win control of the national legislature without monopolizing power. 2

We have to take a step back, however. The American constitution was not designed in the way that a single architect can design a building. It was designed by a collection of constitutional architects, all of whom had somewhat different ideas about how to design constitutional structures, and all of whom had somewhat different economic interests and political dispositions. The final design had to be ratified in the public sphere by hundreds of thousands of citizens.3 In other words, the Constitution of 1787 was produced through a collective process that was conflict-ridden from beginning to end, and the final product does not reflect the interests or ideas of any single individual.

Consider the political preferences of Alexander Hamilton, Treasury Secretary under George Washington, civil war hero, and, in general, a political genius.4 Alexander Hamilton argued during the constitutional convention5 that both the President and Senators should have life-long tenure in their positions, though some suspect this may have been negotiating ploy. In contrast with many American revolutionaries, however, Hamilton was suspicious of the “republican” or egalitarian tendencies of the American people, and he was willing to entertain the idea that aristocratic orders have peculiar advantages. To use the categories of cultural theory discussed in chapter one, Alexander Hamilton was a “hierarch,” albeit a hierarch with some very significant “individualist” leanings. In many ways, the Constitution reflects the disposition of Hamilton, in that it combines hierarchy and individualism. Yet Hamilton did not get all of what he claimed to want in a Constitution. No one did. Given the scope of the conflicting interests and ideas, it is not surprising that the creation of an “inefficient” form of government was ultimately something that all or most could come to agree on.

This chapter will investigate the origin of the American constitution through a consideration of the specific historical situation out of which it emerged. In particular, it will attempt to explain the various features of the Constitution in terms of the ideas of its framers, the interests of the various states which adopted the new national constitution, and the institutional or constitutional “failures” which motivated the creation and adoption of “The Constitution of 1787.”6 I will argue that the Constitution of 1787 reflects an individualist-hierarchical corrective to the egalitarianism of the post-Revolutionary constitutional arrangement.7 The Articles of Confederation tried to create a constitutional order that would enhance the egalitarian values of democratic participation (for white male citizens,) and decentralized federal government.8 In the 1780s, American elites discovered that this system of government was a threat to both individual rights and the common good; somewhat surprisingly, they concluded that, in order for individual rights to be protected, the national government had to become stronger. Yet despite agreeing on this, the elites who created the Constitution were divided due to differing regional political and economic interests.

What changed in this shift from the first American constitution (the Articles of Confederation) to the Constitution of 1787 (which I will now refer to as “The Constitution.”)? On the one hand, the Constitution created a more powerful national government, in that it had a broader range of “policy authority” (the ability to make and enforce law) in comparison with the national government created by the Articles of Confederation. At the same time, it was impossible to increase the power of the national government without balancing different ideological and regional interests. These differences were reconciled by creating a “policy process” that was inefficient by design. Subsequent chapters will investigate the ways in which the political compromise created in 1787 faced the changes and challenges that developed over the subsequent two centuries.

There are many different ways to study American Constitutionalism. According to some scholars, the structure of the Constitution can be understood in terms of the interests of those who created it– and by interests, they often mean the personal economic interests of those who created, promoted, and ultimately supported the Constitution.9 I will not pay attention to that particular interpretation of the Constitution, because it is in my opinion very misleading10. Very few people become revolutionaries in order to become rich; quite simply, there are easier ways to make money, and easier ways to defend your economic interests. This is not to say that the Constitution is the product of political culture alone. The Constitution is based upon ideas about what kind of government is best and appropriate, but it is based upon economic interests as well– not individual interests, but the interests of the various states and regions that the Framers of the constitution represented. So, if we understand “interests” in a narrow sense of “will this aid my investment portfolio?” then this will not help us to explain the structure of the American Constitution. If human beings were motivated solely by economic interests of this kind, the American Revolution would never have occurred.

But there are other kinds of interests– “political interests,” such as the desire to maintain the relative power and status of your home state or region, to advance the prosperity of your fellow citizens, interests that are distinct from ideas because they are rooted in the particularities of geography. We can reject the claim that the Framers’ were pursuing their individual economic interests without rejecting the claim that economic interests, in a broader sense, played a major role in determining the structure of the Constitution. The Constitution was not the product of a philosophy seminar, but rather the result of hard bargaining between professional politicians who were concerned about the fate of their constituents. Of course, it is possible to be a professional politician and a sophisticated political thinker at the same time. This is what makes constitution-making so interesting: it is where philosophy and politics collide.

II. What is a Constitution?↑

There are, broadly speaking, two different ways of understanding the concept of a constitution. A constitution can be understood “holistically,” in the sense of a regime or a way of life, or a constitution can be understood as a set of rules that structures how political power is exercised. A full understanding of American politics—or politics in any society—requires us to bring together these two different meanings of constitution, what we can refer to as the “socio-cultural” and “institutional” aspects of constitutionalism. We will begin, however, by focusing on the institutional meaning of “constitution.” According to the political scientist David Robertson, constitutions shape political power in three major ways: by determining policy agency, allotting policy authority, and structuring the policy process.11 Different decisions about these aspects of constitutionalism reflect different ideas about the goals and purposes of government.

Policy agency refers to the question of who will exercise power and how they will obtain it. In the American context, the Constitution determines policy agency by determining the scope of citizenship, the nature and timing of elections, and the appointment process for non-elected officials. Policy authority refers to the kinds of actions that can be performed by the government and its various branches. The policy process refers to the way in which power is exercised—the way in which laws are made, put into effect, and adjudicated. To understand the logic of the American constitutionalism, you must understand how these three different elements of constitutionalism shape each other.

The Constitution of 1787 was in many ways a response to the failures of American republicanism in the post-revolutionary decade (the 1780s)—though others would say that what appeared as failure to political elites in the post-revolutionary period was, in practice, a successful experiment in radical democracy that was tragically cut short.12 The Revolution expelled the British from the thirteen American colonies– along with a good number of Tories who would help to establish English-speaking Canada. But the Revolution failed in its initial attempts to create stable, self-governing democratic communities. The kind of political order created by the Constitution of 1787 was very different in its emphasis– while the post-Revolutionary State Governments and the first national constitution reflected the tradition of republicanism (a form of egalitarianism), the Constitution of 1787 was closer to the tradition of classical liberalism (a combination of liberalism and hierarchy). There are some– even today– who lament the failure of participatory democracy in the early, more radical stages of the American revolution. Yet even a very brief analysis of American politics in the immediate post-Revolutionary period can illustrate why the first constitution of the United States proved to be a failure in practice.

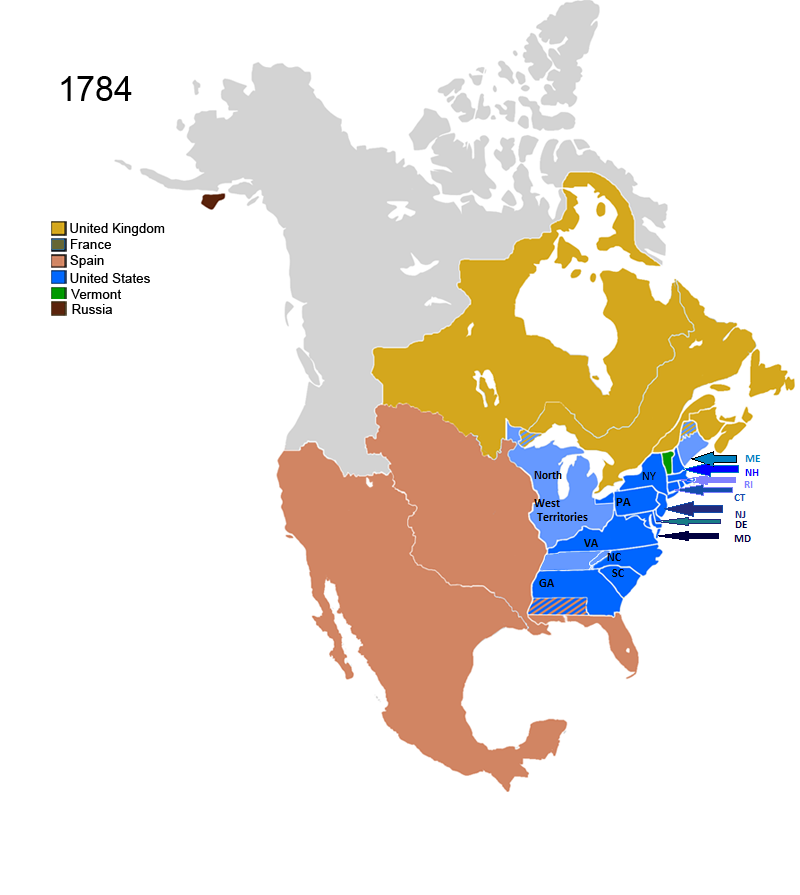

Figure 2.1: European Powers and the American Colonies in North America, 178413

Why did the post-revolutionary governments of the American states under the first American constitution (the Articles of Confederation) experience a crisis of political legitimacy, or a “constitutional failure.”? How was the new constitution shaped by differing ideologies and different interests? What kind of government was created by the new constitution of 1787? By investigating these questions, we will be able to better understand the structure of the American constitution and the way in which it structures American politics today.

III. From the Declaration to the Articles of Confederation↑

We will begin our path from revolution to Constitution by considering the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Continental Congress in 1776, explains the reasons for the revolution against England, and provides a theoretical justification for revolution in general. In doing so, it provides a concise summary of some of the basic principles of “classical liberalism”– it is similar, but shorter and sharper, than John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government. The Declaration summarizes the principles of liberalism as follows. Human beings are created equal, in the sense that no adult human being is by nature the ruler of another. In contrast with bees or ants, there is no natural political hierarchy amongst human beings. The fact that you might be taller than me, smarter than me, stronger or better looking than me, does not entitle you to any degree of political power over me. Human beings require government, but government should be based upon consent– at least in some form. A government not based upon consent– or, a government that fails to fulfill its duty to protect the rights and interests of the people– is not entitled to any respect; it is government by force, and governments based upon force can be removed by force. Revolution is an appropriate response to any form of power which extends beyond its legitimate sphere.

After this succinct summary of the basic principles that all or most American citizens share, the Declaration proceeds to explain why the actions of the Imperial government justify the revolutionary response of the American colonists. These specific complaints reveal the influence of the republican tradition, because in almost every instance they boil down to this: the American Revolution is justified because the imperial authorities are preventing the colonists from governing themselves. The most important right, from the perspective of the American revolutionaries, was the right to control government, the right to select representatives who will have the power to make necessary laws and take necessary actions. So, for instance, the Declaration includes the following specific complaints:

i) The King has refused assent to laws, and he has forbidden his governors to pass laws.

ii) “He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of public records…”

iii) He has dissolved representative assemblies, prevented elections, altered the form of government

The Declaration helps us to understand the mindset of the American colonists– or at least their leaders, and in many ways it is the opinions of the leaders that matters most. The American revolutionaries were concerned with the problem of a distant, authoritarian power that interfered with local self-government. Knowing this, we can practically deduce the kinds of government that they would create in the post-revolutionary period: a largely decentralized confederation, almost an alliance, in which the most important principles were localism and democratic control. The American Revolution was directed against a powerful and absolutist14 state that had failed to respect the rights and interests of its subjects; what Americans discovered in the aftermath of the revolution was that a weak and limited government can also fail to secure the rights and interests of the governed.

The first American constitution, adopted in the midst of the Revolution, was called the “Articles of Confederation,” and it reflected the revolutionaries’ fear of government power and their love of self-government. The Articles of Confederation created a form of government that was more like an alliance than an actual government, because it lacked the central feature of government: the power to enforce its own laws.

In terms of policy agency, the Articles of Confederation was based upon the principle of equal representation of states. The representatives of the national government were selected and paid by state governments; as a consequence, they tended to assess all issues from a state-centered perspective. Given the underlying theory about the kind of association that was created by the Articles, this makes a great deal of sense. The “national government” created by the Articles was simply an international organization, one which was intended to help coordinate the actions of several states, but one which had very limited capacity to coerce the member states. Under this confederacy, according to the terms of the Articles, “every state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence”; the constituent states were not bound into a union, but were like separate sovereign states committed to a treaty.

In terms of policy authority, the national government created by the Articles of Confederation had limited jurisdiction and limited powers. In particular, the national government lacked the power to regulate commerce between the states, and between those states and foreign governments. The powers that the national government did possess—the power to declare war, control a national military, negotiate peace treaties, conduct international diplomacy, and regulate trade with Native Americans—were seriously hampered by lack of any power to directly impose taxes upon individuals.

Furthermore, the policy process created by the Articles of Confederation made it extremely difficult for the national government to exercise the few powers that it did possess. Each state delegation voted as a unit, and thus each state had equal voting power, regardless of the size of their population. Supermajorities of 9/13 were required for many issues–an extremely inefficient way to make decisions. Even more significantly, there was no executive branch in the national government, and therefore national “laws” (such as there were) had to be implemented by state governments.

It is important to note the general character of state governments in the 1780s, because in many ways they were the only real governments in existence at this time in the USA (if we define a “real government” as one that has the power to enforce its own laws and decisions). In the state governments, the powers of the legislative branches were extensive, almost absolute, and the respect of the legislative branches for prerogatives and jurisdiction of the other branches of government– the executive branch, and the courts—was selective at best.15 The state legislatures tended to be very responsive to the desires of their constituents; while attractive to democratic enthusiasts, in practice the experiment with radical democracy was disastrous. The economic crises of the 1780s led to a series of political decisions at the state level that only exacerbated the problems faced by the newly-independent American nation.16

The problems with state governments under the Articles of Confederation fall into three general categories. First, the state legislatures, perhaps motivated by an egalitarian deference to the will of the people, failed to govern in accordance with the rule of law. Secondly, there were problems with coordination amongst the separate states, particularly in relation to trade; even though the states would have benefitted from establishing a free trade zone, the separate state governments were locked in a vicious cycle of trade warfare. Thirdly, the national government was hampered by its structural features, including the absence of a national executive branch and the “supermajoritarian” procedures of the national legislatures; passing laws was too difficult, and the state governments were unable to implement national policies, including policies that were essential to maintain the international standing and security of the various states.

First, let us consider the problems associated with the internal governance of the states under the Articles of Confederation, and in particular, disregard for “the rule of law.” Though they might not have explained it using these exact terms, many political leaders and watchful observers criticized state governments because the policies that they established—particularly debtor relief laws17—infringed upon individual rights and had a tendency to harm the long term economic prospects of the newly independent states. Debtor relief laws were likely to harm the common good as well. The question of whether debt relief is unjust is, in practice, a controversial one, and we need not address every possible argument either for against the notion that debts should be repaid. It is probably impossible to improve upon Cicero’s analysis of the problem, however: “And what is the meaning of an abolition of debts, except that you buy a farm with my money; that you have the farm, and I have not my money?” Many political observers in the post-Revolutionary era continued to sympathize with Cicero’s view that debtor relief laws are unjust because they shatter the legitimate expectation that debts should be repaid, and thereby violate one of the essential elements of the rule of law18—the enforcement of valid promises.

Even those who do not accept that such laws are unjust, or who think that justice should be sacrificed to expediency, should pause to consider whether it would be possible to justify debtor relief on the basis of expediency. A simple thought experiment can clarify the problem—imagine that you have lent a thousand dollars to a friend, and that, prior to being repaid, the government passes a law which annuls all debts over nine hundred and ninety nine dollars. If your friend were to return with another request for a loan, would you be willing to offer it? The answer is obvious. Imagine the consequences of this logic if applied to a society as a whole. In the 18th century, as now, what we call “the economy” depends upon the availability of credit; individuals have always faced some uncertainty when making loans, but if governments showed themselves willing to simply annul debts, or even to make repayment easier by changing the terms of the loan or the value of the currency, then the uncertainty could easily become intolerable.19 Debtor relief laws suggested that state governments were prone to respond all too quickly to short term interests of highly agitated groups of debtors, at the expense of the long term interests of the community.

One could, of course, construct a different narrative about the meaning and significance of debt relief in the early years of the American republic; the narrative I just presented is based upon the general opinions of those who supported political reform, not the opinion of those who wished to have their debts erased. According to some historians, the elites who supported the Constitution wanted to cut off the various experiments of radical democracy that had emerged in the aftermath of the Revolution, particularly those experiments which threatened the rights of property owners.20 From this perspective, the inflationary policies of the state governments under the Articles of Confederation cannot be simply condemned, after the manner of Cicero, as policies that are unjust in themselves; rather, the policies should be evaluated in terms of whom they benefitted and whom they harmed.

There is some truth to this egalitarian perspective on the politics of the Constitution. The Framers of the Constitution were interested in protecting property rights, and many if not most were skeptical about the long-term stability of democratic regimes. Yet the notion that inflationary monetary policies of the revolutionary era were in the interest of the “people” is far too simplistic, for it rests on the unexamined assumption that the debtors who benefitted from currency depreciation were the poor! Both during the revolutionary war and under the Articles of Confederation, many members of the financial elite, particularly in the Northern states such as New York and Pennsylvania, supported inflationary monetary policies, and it isn’t clear that these men were class-traitors, anxious to throw off their unearned privileges in order to help the indebted masses. Rather, those who supported debasing the currency were often land speculators who would benefit from devalued currency and increasing commodity and land prices. The debate over monetary policies during the post-Revolutionary period cannot be understood as a conflict between the many and the few; it was a conflict between people with different kinds of economic interests, not simply a conflict between different classes.

Conflicts over monetary policy were part of the general conflict between “classical liberal individualists” and “egalitarian republicans” during the founding era. From the classical liberal perspective, state legislatures in the post-Revolutionary Era exceeded the bounds of their authority, acting as “legislative tyrants” in a way not dissimilar from the tyrannical acts of the British that precipitated the Revolution. But what does it mean to say legislatures acted tyrannically? In a general sense21, we can think of this by analyzing the three distinct types of power exercised by government—the power to make law (legislative power), the power to enforce law (executive power) and the power to adjudicate disputes over how the law has been enforced (adjudication, or judicial power). A legislature becomes tyrannical when it exercises powers that do not belong to it, just as an executive (for instance, the British administration under King George the Third) becomes tyrannical when it interferes with law-making or legal cases. Most state governments under the Articles of Confederation, influenced by an “individualistic-egalitarian ” suspicion of executive power, adopted constitutional provisions that made state governors (the executive branch) subordinate to the legislative branch. Yet these state constitutions did not have adequate safeguards against what James Madison called “the legislative maelstrom.” State legislatures interfered with judicial proceedings, granted favoured individuals special exemptions from otherwise valid laws, and modified supposedly final judicial decisions. We can see how, from an egalitarian perspective, the supremacy of the legislative branch, the branch of government most closely connected to the people, was distinct from the tyranny of the imperial government. From an individualistic perspective, however, it did not matter whether tyranny had one head or hundreds; interference with the rights of individuals and the rule of law was not made legitimate by being democratic.

In addition to the problems of governance within the states, there were problems related to coordination between the states, particularly in relation to trade. Commercial rivalry was the key source of contention, as states attempted to discriminate against goods exported from their neighbours. Just as importantly, states were unable to co-ordinate as a group to impose protectionist trade measures imposed by other nations—thus, British ships continued to sail into many American ports, even though American ships were barred from trading with English or any of her remaining imperial possessions.

The institutional structure created by the Articles reserved sovereignty for the states, which meant, in practice, that they could refuse to enforce any of the resolutions and recommendations adopted by the national congress. This made the conduct of foreign affairs particularly difficult. The states were reluctant to enforce various treaty agreements, particularly provisions related to the return of “Tory” property and the payment of merchant debts. In response to these provocations, the British refused to uphold their own agreement to vacate a number of forts in what was then the “northwestern” territory of the United States. A similar set of problems emerged in the southwest, as Spain closed the port of New Orleans to American commerce; the national government could not respond to these provocations with retaliatory trade measures or through military action. Some efforts had been made to increase the resources of the national government to collect tax revenues directly, yet these and other amendments were impossible to adopt under the existing amending formula, which required complete state unanimity.

Despite all of the difficulties that Americans experienced governing themselves during the 1780s, it probably would have been difficult to generate enthusiasm for constitutional reform in the absence of the threat of popular violence. The irony of American revolutionary leaders having to crush rebellion was surely not lost on anyone. Shay’s Rebellion, which occurred in Massachusetts during 1786 and 1787, was led by farmers burdened by both private debt and (relatively) high levels of taxation. The rebellion was crushed with relatively little difficulty, but it suggested that the political failures of the Articles were leading to a social crisis. Unwilling to abide by the standards of the rule of law, but fully willing to raise trade barriers against their fellow Americans, the post-revolutionary state governments appeared to illustrate the general defects of democratic government—too much attention paid to particular interests, too little paid to the long-term interest of the political community as a whole. The national “government” created by the Articles was unable to fulfill its own meager responsibilities, as it was hampered by a super-majoritarian decision-making process, lacked any direct executive authority, and relied on the fickle state governments for the resources it required. Economic stagnation appeared a likely consequence, as states raised protectionist barriers against each other, and the Atlantic and Mississippi were closed to American shipping. The institutions of government appeared to be failing.

IV. The Constitutional Convention of 1787: Liberalism, Republicanism, and the Problem of Slavery↑

By 1787– if not earlier– there was general agreement amongst most American elites that the Articles of Confederation were inadequate. States selected delegates to attend a convention in Philadelphia to consider possible reforms to the Articles, delegates who were only assigned the task of developing modest proposals for reform– the Articles of Confederation were to be “mended” not “ended.” They did not follow their instructions. The delegates emerged with a proposal for an entirely new constitution, and in addition, they proposed a mode of ratification or adoption that violated the amending formula found in the Articles of Confederation. Thus, the adoption of the Constitution of 1787 was not only the second American constitution; it was the product of the second American revolution– a major institutional change or political development took place outside of the established legal-political framework, though this time without the need for violence.

Widespread attachment and veneration of the Constitution in later years would mask the political disagreements and conflicts that were part of “constitution making.” It reminds one of the famous cliche attributed to the 19th century “Iron Chancellor” of Germany, Otto von Bismarck, which I will paraphrase loosely: if you want to eat sausages, or respect the law, never look at how they are made. The politics of Constitution making was in many ways deliberately obscured by the defenders of the new Constitution– for obvious reasons. In order to get the Constitution ratified, proponents of the new constitution wanted to emphasize its positive benefits, not its potential limits. James Madison, one of the authors of the Federalist Papers, defended the new constitution despite the fact that it was far from his ideal. This only shows the greatness of men like Madison and Hamilton. Rather than whining about not getting their way, they acted to achieve the best possible outcome under the circumstances; they had the wisdom to recognize that, in political life, wisdom must be combined with consent.

“Classical Liberals” such as Alexander Hamilton and James Madison22— the two main authors of the Federalist papers– were unable to impose their favoured political theory upon the USA, due to the presence of competing sectional-regional interests, and due to competing ideological forces. The Constitution was based upon a compromise between the traditions of liberal individualism and republican egalitarianism; it was a compromise between the various sectional interests of the states (particularly in regards to the issue of slavery); it was a compromise between the interests of the smaller states and the larger. Yet most of all, the Constitution was a compromise between those who feared government power, and those who recognized that a greater degree of national authority was necessary if the American experiment with democracy was to survive.

Let us begin with the “liberal” agenda at the Constitutional convention—an agenda which combined elements of individualism and hierarchy. We sometimes associate classical, Lockean liberalism with libertarianism, which we sometimes associate with anarchism; we sometimes think that there is a close connection between classical liberalism and fear of government. This is not exactly correct. Liberals fear deficient government as much as they fear its excesses, and liberals– such as James Madison– were mostly focussed on the deficiencies of government power during the era of the Articles of Confederation. Liberals such as Madison were concerned with the limits of national government power under the Articles of Confederation, and the excesses of state governments. They hoped to limit the power of states to interfere with property rights; they hoped to limit the power of state governments to enact laws which created trade barriers between the states; they wanted, most of all, to limit the direct power of state governments to influence the national government. Some might well have wished to eliminate state governments entirely. As we will see, Madison’s theory of democratic government, outlined in Federalist Paper #10, gives an indirect explanation of why a single national government might in many ways be preferable to a federal form of government. One way to think about the liberal agenda is that, for Madison, limited government in the nation as a whole required a strong and authoritative national government, though not necessarily a “big government” in the sense of a modern welfare state. Madison did not want to use a strong national government to regulate liquor licenses or determine nap times for day care centers; he wanted a strong national government to prevent states from interfering with commerce, the currency, private rights, and international relations.

The logic of the Constitution shows that, in general, it aims to limit state power in order to limit state mischief; to achieve this, new powers had to be transferred to the national level, and the national government had to be able to govern the people directly—it had to be able to collect its own revenues and enforce its own laws and treaties without having to rely on the states. Trade warfare amongst the states was harmful to all, and the solution was rather simple: the national government should have expanded (or even exclusive) power to control commerce between or “amongst” the states. The national government should be able to levy its own taxes, and even more importantly, it must have the power to enforce its own laws. The selection of national representatives should, as much as possible, be disconnected from state governments.23 Going further, there should be strict limits on the legislative power of states, so that property rights will not be subject to the whim of transient majorities. James Madison even hoped that the national government would have the ability to veto state laws. In addition, liberals supported national power because they were alert to the problems of foreign intervention. The inability to enact and enforce treaties and the inability to mount a united foreign policy would leave the former colonies subject to the depredations of foreign powers. The general tendency, represented by liberal thinkers such as Madison, was to support new national power in order to promote liberal goals: prosperity and security through the protection of rights, the rule of law, and increased military strength. The liberals who supported these developments still believed in limited government; but they did not believe in weak government, and they did not necessarily think that the best government was the government most closely connected to the people.

Most of the American founders did not want to create a constitution that was only democratic in character. From their perspective, democracy meant the rule of the people; “the people” meant the “the poor”; and the unconstrained rule of the poor was no more desirable than the unconstrained rule of an aristocratic or oligarchic elite. According to Alexander Hamilton, “society naturally divides itself into two political divisions, the few and the many, who have distinct interests.” This observation, made during the constitutional convention, was of course not original; Aristotle observed that, in free societies, political conflict tends to take the form of “oligarchs vs democrats.” Like Aristotle, Hamilton (and others) thought that the best regime in practice would be neither democratic, nor oligarchic, but rather a “mixed regime” that could accommodate the interests of all. Thus the Constitution was not intended to be entirely democratic, even if it has democratic elements. But neither was it meant to serve the interests of the few. This explains the curious mixture of democratic and anti-democratic elements in the constitution.

James Madison stated even more directly the reasons why, from a liberal perspective, the scope of democracy should be curtailed: “The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, .(is an) insuperable obstacle to the uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government.” (Federalist Paper #10) What does he mean by this? The primary purpose of government is to protect the ability of people to use their own different capacities, not least for the acquisition of property. (This is not the only purpose of government, of course…). Given this perspective on the purposes of government, and given their assessment of state governments under the Articles of Confederation, it is not surprising that liberals such as Madison and Hamilton were interested in creating a form of government that would not be entirely democratic. Stated differently, they wanted to create a form of government that would combine respect for property with respect for the people, respect for wisdom with the requirement of consent.

Those with a more “republican” orientation– such as eventual opponents of the new constitution such as George Mason from Virginia, or crafty negotiators such as Roger Sherman of Connecticut — agreed that the existing scheme of government under the Articles of Confederation was defective. But they wished to maintain as much “republicanism” as possible in the new constitution, while still remedying the defects of the old constitution. The goals of republicans can be easily summarized: they wished to create a government that would be as decentralized as possible, they wanted the states to have a direct influence on the national government; and they wanted the powers or jurisdiction of the national government to be as limited as possible. Many features of the American government reflect the influence of republican thinking– that is, the general desire to keep government as close to the people as possible, combined with scepticism and fear of centralized government powers. We cannot account for the structure of the constitution if we do not take this ideological element into account.

The conflicts over the Constitution were not only based upon different beliefs or ideologies. State representatives had different interest depending upon the size of their state, and depending upon the position of their state in the American political economy. Small states were of course concerned with questions of “policy agency”: if representation in the national government was based entirely upon population, how could the smaller states be certain that the more populated regions of the new nation would not abuse their power to the disadvantage of small states? Thus, one of the central issues in the constitutional convention was whether representation would be based upon population alone, or whether “regions” or “states” could be represented as well.

Despite the differences between the small and larger states over questions of representation, all Americans shared similar economic interests in strengthening the power of the national government. If you lived in the more developed north eastern states, a stronger national government would help to promote inter-state and international trade; if you lived in one of the more agriculturally-oriented region of the south and west, a stronger national government would be able to offer greater protection from foreign enemies, it would enable expansion to the west, and it would promote a coherent national trade policy that would open up Europe and the British Empire to American trade.

The issue of slavery, however, raised a combination of economic and moral issues that divided the states– and while there were some who may have been sincerely opposed to slavery, it was evident that any serious attempt to eradicate slavery would make the new national government impossible. Thus, the Constitution created a compromise between the slave states and the more or less non-slave states: for purposes of representation, slaves were counted as “three fifths” of a person24; the power of Congress to limit the slave trade was curtailed (but not eliminated); the fugitive slave clause protected the institution of slavery by preventing any state from granting freedom to escaped slaves. That slavery was accommodated by the Constitution is beyond doubt; whether or not any other course of action would have helped bring slavery to an end more quickly is much more in doubt.

There were thus several different types of political conflict involved in the creation of the Constitution. Small-r republicans worried that the new national government would re-create the problems experienced under imperial rule; they feared a newly empowered but distant national government would undermine local autonomy and serve the interest of wealthy elites. Leaders and citizens from small states worried that their interests would be subordinated to the interests of the more populated states; slave states (that is, states where slavery played a large economic role) were worried that the national government would immediately attempt to interfere with slavery. To be adopted, the Constitution had to accommodate all of these various concerns.

The Virginia Plan was the first major proposal for constitutional reform at the constitutional convention in Philadelphia, and its proposals reflected the interests of the larger states. The salient features of the Virginia Plan were as follows. First, the plan proposed a legislative branch with two separate “houses” or chambers: a lower house elected by the people, with representation based upon population, and an upper house ( what Americans would come to call a “senate”) chosen by the lower house. In addition, the executive would be chosen by the legislature, as would the Supreme Court. The power of the legislative branch would be extensive; the plan proposed that the legislature should have a broad, almost indefinite grant of authority, and in addition, the plan proposed that the new national legislature should have the power to veto state laws.

There were many sources of disagreement in regards to this initial proposal. The most serious obstacle was the upper house of the legislative chamber– the Virginia plan envisioned representation by population in both the lower and upper houses. The smaller states were obviously concerned about a scheme that relied almost entirely on representation by population. One representative stated that he would rather submit to a monarch or a despot than submit to such a system. The smaller states had little to gain from joining a government that privileged national majorities; they had their own ideas about what form of “policy agency” would best suit the new nation.

The smaller states such as New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland united behind a proposal dubbed “The New Jersey Plan.” While the Virginia plan contemplated a wholesale revolution in government, the New Jersey Plan proposed mere alterations in the Articles of Confederation. The central change was to allow the national government more extensive powers to regulate trade and commerce. But the smaller states were also concerned with protecting the prerogatives of state governments– they did not want a national government with vague, undefined powers, controlled by the representatives of the larger states, as they thought that this government would be a kind of vortex, sucking all manner of power into itself. To prevent the consolidation of power, the New Jersey Plan proposed direct state representation in the legislature, and the direct influence of state governments in the selection of the executive.

The Constitution of 1787 was a compromise between these two plans– though we should note that the final outcome would reflect the goals of the Virginia Plan more than the New Jersey plan. The central component of the compromise was the agreement to accept equal representation of the states in the Upper Chamber, or the Senate. Representation in the House of Representatives– the lower house– would be based upon representation by population, with slaves counted as 3/5ths of a person for purposes of determining representation.

In terms of policy agency or selection, the Executive Branch was in many ways the most innovative aspect of the Constitution. Most important of all was the fact that the Chief Executive– the head of the national government– would not be selected by the legislature, nor would the Chief Executive require the confidence of a majority of the legislature in order to remain in office. The President would not be responsible to the legislature– though the delegates thought that the central duty of the President in domestic affairs was to enforce the laws made by Congress. Interestingly, it is not even true to say that the President was meant to be responsible to the people.

The President is not selected by popular vote, but rather selected on the basis of the electoral college. In this system, every state is given a number of electoral votes, based upon their number of representatives in the House and Senate. Large states have the most influence in this system, but this is partly counterbalanced by the addition of two electoral votes to every state, regardless of their population. Neither the Senate nor the House play any direct role in selecting the President25; technically speaking, neither do the voters. The members of the electoral college select the President. Today, this consists of a slate of individuals who have pledged to give their vote to a particular candidate. But this is not how the system was meant to function; to be blunt, the electoral college was meant to operate in a much less democratic way.

The original conception of the electoral college was as follows: the states would elect a set of local notables, who would then have the opportunity to debate amongst themselves, and select a candidate for the President based upon their own assessment of who would best perform the role. What does this tell us, if anything, about how the founders viewed the Presidency? The People? This is something that we will return to– as the transformation of the Presidency is one of the central features of American political development.

The most significant feature of the national government in terms of policy authority is article one, section 8, which establishes or seems to establish that the national government will have power over a limited number of policy fields. Most importantly, Congress is given the power to regulate commerce amongst the states and with foreign nations. In addition, Congress has the power to tax, borrow, and coin money, to create and regulate a national military, to create a national judiciary, as well as a small number of other powers. Yet the revolution in government power represented by the Constitution was still influenced by the “republican concerns” that had shaped the Articles. Many proponents of constitutional change had argued for an extreme nationalization of power, including a general legislative power for Congress, and even some form of national veto over state laws. This was not achieved — the new government would be a real government, but it would not be nearly as powerful as some had hoped and others had feared.

The policy authority of the national government was not only limited by the enumeration of powers in Article One, Section 8; it was also limited by the explicit restrictions on national power found in Article One, Section 9. The national government was prohibited, for a period of two decades, from interfering in the international slave trade. The subsequent sections of Article One—a prohibition against the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus26, bills of attainder, and ex post facto laws—aim to insure that national power will be exercised in accordance with the rule of law, while the provisions that limit and structure the taxation power of the national government help insure that tax policy will not be used to favour one region or state over others.

The extreme nationalists failed to get what they wanted, but in some ways what they did get was good enough, if you assume that their central goal was to prevent the states from acting in an asinine fashion. But how can the national government restrict the states, when the national government appears to have such limited powers? The answer is that the courts played a crucial role in the new scheme. The Framers must have assumed that the courts would apply the Constitution in such a way that state governments could be limited without direct congressional action. The problem is that the role of courts was not particularly emphasized by the Framers of the constitution, even though the significance of national courts for the system they created would become evident at a very early stage.

The Constitution was produced out of a series of conflicts rooted in sectional and ideological differences. The final product reflected the general consensus that the national government required additional power. But it also reflected, in various ways, concerns with the threat of national government power. Small states secured equal representation in the Senate; slave states secured explicit protections for their most important economic interests (slavery). The most significant changes– the changes that would be hardest to defend– were the vastly expanded legislative and taxation powers of the national government, and the power of the executive. From the perspective of those who opposed the Constitution, this new arrangement would return Americans to the pre-Revolutionary condition, in which they would be dominated by a distant, powerful national government, indifferent to their interests and immune to their will. How could this new monstrosity be defended?

V. Defending the New Constitution: The Federalist Papers↑

The classic defence of the Constitution is found in a series of newspapers editorials published in New York during the ratification debates– these are known as the “The Federalist Papers.” The Federalist Papers were written by James Madison of Virginia, Alexander Hamilton of New York, and John Jay, also of New York. Hamilton and Madison had participated in the constitutional convention, though arguably Madison had much greater influence. Some scholars point out that we should take the Federalist Papers with a large tumbler full of salt– the argument is that they were written as part of a propaganda campaign, and therefore cannot be fully trusted as interpretations of the Constitution. I think this is mostly nonsense. It is true that the Federalist Papers do not reveal the true preferences of Hamilton and Madison, as both men would have preferred to have a much stronger national government– they probably would have liked to eliminate the constitutional status of state governments, and treat them merely as administrative units. However, they were both aware that they were not philosopher kings– they had to defend the actual result of the convention, not what they would have preferred in the abstract. As an explanation and defence of the Constitution, it has no parallel; whatever their reservations about its features, there is no reason to think that they distorted the results of the convention.

Of course, there are some important rhetorical elements in these papers. The theme of many of the earliest papers is the various threats that Americans will face if they fail to adopt the new national government. The initial essays engage in sort of thought experiment: what will happen if we remain governed by the Articles of Confederation? Though speculative, the conclusions of Publius (the collective nom de plume of the three authors) were very plausible: in the absence of a stronger national government, the American states will continue to experience economic disarray; they are likely to experience foreign intervention, or foreign meddling; they are even likely to experience intramural discord and conflict, once the bonds of revolutionary brotherhood have become a distant memory.

To summarize Hamilton’s position: the only thing we have to fear is poverty, war, and death. The Federalist Papers do not rely on fear alone, however. Publius attempts to explain why a new, more powerful national government will avoid the problems that Americans experienced under British rule, and the problems Americans experienced under the rule of their own state governments and the Articles of Confederation. The entire set of essays aims to make this point, but the most important statement of the general argument can be found in Federalist Paper #10, written by James Madison.

Many political leaders (e.g. the individualist-egalitarian republicans who would come o to be known as the Anti- Federalists) thought that a powerful and effective national government would be a threat to liberty. Federalist Paper #10 (written by James Madison) attempts to explain why this is not so, by establishing why large-scale, democratic societies can effectively address the problem of “faction.” What is a faction, and why are factions a problem, according to Madison? The idea of “faction” is easily confused with the value-neutral term “interest group,” but it is important to recognize the difference. Here is how Madison defines the term: ” By a faction I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority, who are united… by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” It is important to see that a “faction” can consist of the majority of citizens; we can speak of a “majority faction.” Majority faction is the key problem for Madison, because the democratic principle can– in most instances– prevent or limit the power of factions comprised by a small number of citizens. Majority rule can limit exploitation of the many by the few; but how can majority rule prevent exploitation by the majority? That, in essence, is the problem of democracy.

Madison rejects the idea that the problem of faction can be solved by traditional republican remedies– that is, he rejects the idea that factionalism can be solved by eliminating sources of political dispute, or sources of conflicting interests. According to the republican tradition, you eliminate faction by creating unity, whether understood in terms of common economic interests, common religious beliefs, common political attachments, etc. Yet this rarely seems to have worked very well– small scale democracies, such as the city-states of Ancient Greece, were constantly bedeviled by internal strife and civil war. Even if this was effective, it would not be worth the cost– liberty of thought, action and belief would have to be eliminated to cure the problem of faction.

Monarchies are able to eliminate or control faction while maintaining a considerable scope for individual freedom– every freedom except the freedom to participate in government. Without that freedom, recent history suggested that other freedoms would be undermined as well. Madison’s argument– a new one– is that a remedy to faction can be found that is fully compatible with representative government.

The answer is relatively simple: the problem of faction can be solved by extending the sphere of government, that is, by expanding the number of citizens and the number of interests that are the basis of the new form of government. The very size and scale of the territorial jurisdiction of the new national government will make that government less likely to abuse its power– less likely to act on “factional” impulses. A simple thought experiment can clarify Madison’s meaning. Imagine a political society that is the size of a small town or city. Imagine– as is often the case– that this small town is dominated by a single industry, or perhaps by a single religious sect. It is easy to see how those who own (or who benefit from) the most important industry would be able to influence the laws of the town; it is also easy to see how the same might be true for a dominant religious group. The key point– the absolutely key point to see– is that in small scale society there is likely to be a permanent majority, a permanent elite that is always in a position of power, on issue after issue, on vote after vote.

Madison’s argument for an extended sphere– a government that encompasses a multiplicity of differing interests– is really an argument for a society in which it is difficult to form a permanent majority. There will always be majorities on any given issue, but in a large-scale society, that “majority” will shift over time– it will be based upon differing alliances that change from issue to issue, and not only from election to election. We have a tendency to think about politics in ways that are more abstract than Madison, particularly in relation to economic interests– the kinds of interests that Madison thinks of as being an unavoidable source of political conflict. We have a tendency to think of many political issues in terms of the varying interests of “the wealthy” and the “the poor.” Madison would say that, though the wealthy will always be with us, they will not always have a unified interest. In a large scale society, wealth will come from a variety of sources– agriculture, commerce, trade, industry, the professions, and so on and so forth. Differing sources of wealth will create differing interests, depending on the nature of the political issue. In order to achieve any of their goals, differing economic groups will have to compromise– the result, not always, but in general, will be that the laws will reflect the interests of as many people and groups as possible, hopefully approximating the common or general interest of all citizens. Stated somewhat differently: in a large scale society, it will be difficult for one unified group to dominate, and therefore laws– if they are to be adopted– will tend to aim for the general good.

Now, this argument is based upon some assumptions that are contestable. In many ways the subsequent development of political science in the USA is an attempt to answer the following question: does the Constitution actually prevent the problem of faction, whether majority or otherwise? Are there permanent majorities in American politics, who direct national power as if they were the oligarchic overlords of a Greek city state?

The promise that Madison makes regarding the cure for faction is of course only addressed to citizens– if you lack citizenship, if you are slave, then you are under the thumb of a permanent majority faction.

Madison did not think that the multiplicity of interests would be the only advantage of a large scale, commercial republic. He also thought that the quality of legislators would be better at the national level. I suppose this seems somewhat naive now. The idea is that all legislative assemblies must be approximately the same size; big enough to avoid dominance by a small cabal, small enough to avoid utter chaos. As the national assembly will draw on a bigger talent pool, it is likely that legislators at the national level will have a higher degree of ability (including the ability to prefer the common good to narrow interests.) In addition, Madison thought that better people would be attracted to national service, because serving the national government will be much more awe-inspiring than serving in some backwater state government. Finally, while shenanigans will occur, it will be almost impossible to use widespread fraud in such a way as to distort the outcomes of national elections– it would take too much organization.

The structure of American government also reflects Madison’s concerns regarding the problem of faction, in particular, majority faction. “Policy agency”– the selection of leaders and representatives– and the policy process are arranged so as to make it difficult for majorities to control the national government. Federalist #10 explains the socio-geographic elements that can help limit majority factions. The arrangement of elections, and the structure of government power in the Constitution is meant to create further impediments to majority rule.The new Constitution would make it difficult to form majorities in the legislative branch through its mode of electing representatives and senators. By shaping the constituents– the people who do the electing– and by shaping the timing of elections, the Constitution will make it difficult for majority will to dominate law making.

For instance, for any proposal– any “bill”– to become a law, it must be passed in identical form by the House and the Senate. However, the mode of elections will tend to make the House and Senate very different legislative bodies; different in both their orientation and outlook. To begin with, the House is based upon representation by population; the Senate is based upon equal representation by state. What effect will this have? At the most general level, we might speculate that the Senate will tend to favour the interests of the less populated regions of the country; it is possible, though not necessarily likely, that a majority of Senators in a given vote will represent much less than a majority of the population. This was intentional. The institutions of American government were never intended to confer equal voting power on individuals; it was meant, in part, to represent regions as well. In addition, Hamilton thought that the Senate would tend to represent the propertied interest– and thus serve as a necessary counter-balance to the House of Representatives.

Next, consider the timing of elections. Every member of the House of Representatives goes up for election every 2 years. The senate is elected based upon staggered 6 year terms, with one third of the Senate (approximately) going up for election every 2 years. How will this arrangement make the legislature less responsive to majority will? Change will come slowly in the Senate; Senators will also have a longer time horizon, and thus might be more willing to challenge unwise proposals (given that their trial before the public occurs less frequently.)

We finally turn the issue of “constituency,” as it was initially arranged in the Constitution. The House of Representatives differs from the Senate not merely because it would be based on representation by population, but because the members would be selected by the populace. The Senate, on the other hand, was originally selected by state legislatures. This was abolished by many states themselves over the course of the 19th century, and was permanently abolished with the adoption of the 17th amendment in 1917. By allowing state governments to select Senators, the Constitution added yet another protection for those republicans concerned with the threat of a distant and authoritarian government; Senators would be unlikely to trample upon the power and prerogatives of the legislators who had put them in office.

The Constitution was the result of the conflict between the liberal aims of many of the founders, the competing traditions of republicanism and ascriptive hierarchy, and the contrasting sectional interests of the nation (e.g. large states vs. small, slave vs. free.) The result was a government that was powerful in many ways, but a government that would be inefficient at creating laws. In particular, this government had only a limited responsiveness to the “will of the majority.” The various “inefficiencies” built into the legislative process– found in its prescriptions regarding policy agency, authority, and process– had one general aim: limit the formation of “majority faction.” The greatest question in American politics is this: has that in fact occurred? Did the constitution create a system of government that is able to balance or “mix” the interests of various classes, particularly the interests of the few and the many? If not , what has been the cause? What might be the remedy?

One thing we know for certain: the Constitution could not protect the rights and interests of those who were excluded from the political system entirely. The topics that we will explore in upcoming chapters– political development, federalism, civil rights, and civil liberties– will frequently address the status of African Americans within the American political system. But we will also explore how many thinkers, social movements, and political leaders became dissatisfied with the Constitution of 1787. Many changes occurred on account of these various sources of dissatisfaction. But the basic structure of the Constitution remained, and it continues to shape the patterns of contemporary American politics.