Outline of the Chapter

Learning Objectives

- Explain what interests groups are, and how they differ from and are related to political parties and social movements.

- Explain the distinction between different economic interest groups and public interest/citizen groups. Why are certain kinds of economic interests more likely to be represented by interest groups than others? Explain this issue using the concepts of the “collective action problem,” public goods, and the “free rider incentive.”

- Explain why some periods of American history produce a larger number of idea-oriented social movements, movements that often turn into organized interest groups.

- Explain how the institutional structures of American government (in particular, the separation of powers, the electoral system, and the judicial system) provides opportunities for interest groups to influence public policy.

- Explain some of the different political strategies that are available to interest groups.

- Explain the differences between the pluralist and “power elite” theoretical perspectives on interest group power. Why does the power of interest groups depend upon the kind of policy at stake?

I. Introduction– The Financial Crisis of 2008 and the Puzzle of Interest Group Power↑

Who rules the United States? Does the American constitution enable the public to control public policy? Have the various institutional changes that have altered the constitutional system—changes in federalism, constitutional law and rights, as well as the development of the bureaucratic state—enhanced or undermined popular representation? This chapter will consider these questions by examining the role of interest groups in American politics. There are no simple answers to these questions. Our ability to know the precise effects of interest group power is limited, because it is extremely difficult to determine whether the American federal government, responds to the interests of “the public” or the power of interest groups. Nevertheless, even though it can be difficult to determine the precise impact of interest groups on American politics, we can determine the features of American government that enable interest group power, and the changes in American society and politics that have shaped the character of interest groups over time.

Theories of interest group power in American politics fall into two broad categories: pluralist theories and “power elite” theories (with many individual theories falling somewhere between these two extremes.) Pluralists argue that interest groups play a relatively benign or even productive role in politics, particularly in American politics. Pluralists do not believe that interest groups necessarily “dominate” government in a way that has an adverse effect upon society. Pluralists think that James Madison’s predictions about the character of American society in Federalist Paper #10 were correct. “Power” in American society is widely distributed amongst different groups, not least because political power (understood as the ability to exert influence over others) has many different sources: wealth, knowledge, education, numbers, organization, fame, etc. Given the wide variety of sources of power, and given the conflicts between different kinds of economic elites (the kinds of conflicts anticipated by Madison), interest groups in the United States do not form an oligarchic ruling class. There are many different kinds of interest groups, many different ways to exercise power within the American political system, and no permanent ruling class of interest that is always able to achieve its ends. Interest groups, therefore, do not distort American democracy; they are part of American democracy, and provide important links between government and the people. Without interest groups to provide information, mobilize the public, and lobby government officials, American society would arguably be less democratic.1

Critics of pluralism argue, in different ways, that the “chorus” of interest-groups in American society “sing with an upper class accent.”2 One modest version of this approach– sometimes referred to as “neo-pluralism”– is that interest group power is distributed unequally, because the sources of power are distributed unequally; the interest of the most wealthy in society are far better represented than the interests of the middle-class and the poor.3 “Power elite” theorists make a stronger claim: according to this view, the American political system is dominated by a relatively small class of individuals who hold major positions in government, the military, and big business; power, rather than being shared amongst a variety of contending and shifting interests, is instead monopolized by a ruling caste.4

Evaluating pluralist and power-elite theories of interest group power is no easy task. Consider, for instance, the American federal government’s response to the financial crisis of 2008. The crisis was one of the most disruptive political events of recent decades. A collapse in housing prices destroyed or undermined major financial firms, which caused a deep and prolonged recession, and, arguably, led the public to reject the incumbent Republican administration of George W. Bush. The financial crisis also led to some of the most extensive government economic intervention in recent memory. Both Republican and Democrat politicians were willing to use the immense resources of the national government to bail out financial institutions, as well as non-financial firms such as General Motors. The financial crisis and its aftermath appeared to confirm what many critics of American public policy had long suspected: legislators and regulators at the national level, rather than serving the public good, had succumbed to the power of private interests. According to this perspective, Republicans and many Democrats enabled the rampant speculation that had created the housing bubble5 by repealing laws such as the Glass-Steagall act6, and by failing to update the regulatory framework to prevent banks and mortgage lenders from taking excessive risks. Rather than allowing the guilty parties to pay for their bad bets, the government stepped in to rescue many of them from the adverse consequences of their decisions. The Troubled Asset Relief program (TARP), which was part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, directed almost $700 billion dollars in federal money to distressed financial institutions. The Federal Reserve loaned financial institutions nearly twice that amount of money in response to the crisis as well.7 In good times, governments had provided the financial industry with deregulation; when times turned bad, the American state was there to rescue capitalists from the consequences of capitalism.8

Yet some might claim, with good reason, that the federal government’s response to the financial crisis served the public interest. While it is difficult to know what would have happened in the absence of government intervention, it is possible that a complete breakdown of the American banking sector would a have occurred, a breakdown that would have threatened the livelihood and savings of millions of Americans. Cabinet officials, bureaucrats, and representatives did work closely with Wall Street during the crisis, but this was unavoidable—devising and implementing the necessary policies would have been impossible without the expertise and cooperation of major players in the financial industry. Furthermore, the Obama administration, working with its allies in Congress, passed the Dodd Frank Act, a set of comprehensive banking and financial regulations that place greater restraints on Wall Street in order prevent gigantic financial crises from occurring again. From one perspective, then, the financial crisis seemed to suggest that the power of even the most resourceful industries was not unlimited; government power was asserted to protect the public interest, and not simply to protect the profits of private industries. As Barney Frank, then Chairman of the House Financial Services committee put it, “when money comes up against the people, it never wins.”

If one investigates the details of Dodd Frank, one can quickly see that the story is more complicated than it first appears. It is true that the financial industry opposed many aspects of the law. In practice, the financial industry exerted considerable influence in the legislative process—through direct lobbying of individual members of Congress and congressional committees, and through connections with major White House officials and Congressional advisers. The legislative process that led to the passage of the Dodd-Frank financial reforms revealed that, while Congress often responds to widespread public concern and widespread public discontent, interest groups shape the details of policy-making because of their resources, connections, and access to information.9 It is a pattern that is reflected in many of the most important aspects of American policy. Like many aspects of American politics, the example of the financial crisis provides evidence for both pluralist and power elite theories of interest group power.

II. What are interest groups?↑

Pundits, politicians, and ordinary people often discuss the role of interest groups in American politics—or more likely, the nefarious and undemocratic influence of interest groupsYet what exactly are interest groups? While any definition will be imperfect, interest groups can be defined as organizations that seek policy influence without directly controlling government. Thus, interest groups are distinct from public officials, such as legislators and bureaucrats whose powers are defined by law. Interest groups are also distinct from political parties, which aim to achieve political power through winning elections. Interest groups are usually distinguished from broader social movements. One can be part of a social movement—one can be a feminist, a union member, an environmentalist, and evangelical Christian, or a member of the “alt-right”– without belonging to a organization dedicated to those goals. Yet the lines between social movements and interest groups can be porous. Organizations have defined membership, they almost always have a hierarchically organized structure, they have (or aim to acquire) resources, and they engage in long-term planning and political action. Interest group organizations include what we might normally call “lobbying groups” that pursue their goals through direct contact with policy-makers, as well as organizations that rely on mass mobilization and public protest (such as the Black Lives Matter Movement) In between business lobby groups on the one hand and the Black Lives Matter movement on the other are hundreds of thousands of organizations, all of which have different kinds of members, different resources, and different political tool-kits.10

Understanding the role played by interest groups is crucial for understanding American government and politics, as the power of interest groups raises serious questions about the effectiveness and even the legitimacy of the American constitutional order. We should be open to the possibility that interest groups are both potential problems in a democratic society and invaluable resources. As James Madison pointed out in Federalist Paper #10 (though using different language), a free society will inevitably produce interest groups who wish to influence public policy. Madison, and thinkers of his era, were well aware that many interests within society pursued goals that were not compatible with the common good. To eliminate the power of interest groups completely, however, you would have to eliminate the ability of people to engage in political and social life. In fact, rather than being a threat, the ability of people to form various types of private groups would help to maintain an economically vibrant and politically active nations. The ability to form interest groups, or any kind of private association, was protected by law; freedom of assembly was recognized explicitly in the federal Constitution, as well as in many state constitutions; freedom of association was a generally accepted norm. American citizens took advantage of this, forming a wide variety of private organizations that pursued collective (though not necessarily public) interests; fraternal clubs, business associations, religious societies, and labor unions flourished in early 19th century America, something that was noted by foreign observers.11 Rather than being a nation of atomistic individuals, Americans appeared to be a nation that had perfected the art of association. The vast amount of interest group activity in the contemporary United States is a reflection of that tradition of voluntary association.12

Interest Group Organizations and the Federal Tax Code: Section 501 and Section 527

In the United States, federal law (especially tax law) structures various kinds of interest group organizations, usually by providing specific types of tax-benefits depending upon the activities undertaken by the interest group organization. Here are the main categories of federal law that shape public interest or “policy oriented” organizations:

501(c) 4 Groups (Social Welfare Advocacy): This category deals with social welfare advocacy groups, which means groups who engage in some kind of activity that aims at the “common good” or “general welfare.” These groups can engage in political activity, but political advocacy cannot be their primary purpose. In practice, this means that 501c4 groups cannot spend more than 50% of their resources on political advocacy. They are tax -exempt, but contributions to these groups are not tax deductible. 501c 4 groups can engage in political activism, such as recommending various kinds of policy changes, but they cannot give direct donations to federal candidates.

Some of the most prominent interest group organizations in the United States are organized as 501(c) 4s. For instance, powerful interest groups such as The American Association of Retired People (AARP; 37 million members) and the National Rifle Association (5 million members) both fall within this category. Other prominent 501 c 4 organization include Americans For Prosperity (associated with the libertarian-leaning Koch Brothers), Crossroads GPS (a “social welfare organization” created by Republican political strategist Karl Rove), and Majority Forward (a left-leaning group whose purpose is to promote voter registration; though less well known than American for Prosperity, Majority Forward spent almost as much money in the 2016 electoral cycle.)13 One additional advantage of this form of organization is that 501 c 4 groups do not need to make their donor lists public. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as “dark money” organizations.

501 c 3 organizations aim to educate the public about different aspects of politics, but they differ from 501 c4 organizations in that they cannot engage in electioneering activity. However, these organizations can receive tax deductible donations from individuals and donations. Some of the most prominent “think tanks” in the USA are organized as 501 c3s, such as the Brookings Institution, the Cato Institute, and the American Enterprise Institute. In addition, foundations that make various kinds of grants to social movements and interest groups are organized as 501 c3; prominent examples include the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.

The final part of the tax code that is relevant to interest group organizations is section 527. Somewhat confusingly, section 527 deals with organizations that are highly regulated in terms of how they can raise and spend money (political action committees) and organizations that operate under relatively few constraints. Political action committees are organized by interest groups of various kinds; their primary purpose is to direct money to particular candidates. PACs must follow a variety of specific legal requirements regarding how they raise, donate, and spend money:

- PACs must raise money from a least 50 different people

- They must contribute to at least five candidates

- They contribute $5000 per campaign to a candidate (e.g. they can give a candidate $5000 for a primary campaign, and they can give another $5000 in the general election.)

Unlike 501 groups, section 527 organizations are organized primarily for direct political activity. Unlike political action committees, section 527 organizations cannot coordinate with parties or candidates, and they do not donate money to candidates. This organizational form was particularly prominent in the aftermath of the 2002 Bi-Partisan campaign finance reform bill, as the 527 groups could receive unlimited donations from individuals as long as they did not coordinate with party or candidate electoral campaigns. The most famous example of a 527 group is “Swift Vote Veterans for Truth,” which ran a variety of advertisements in the 2004 electoral cycle criticizing Democratic candidate John Kerry, based upon dubious claims about his record in Vietnam.

Section 527 are distinct from the “Super-PACs,” an organizational form which has become more prominent in recent years. Super-PACs are distinct from 527 organizations in that they can advocate for the defeat of specific candidates, though like the 527 organizations they cannot coordinate with political parties or candidates. Most importantly, Super-PACs can receive unlimited donations from individuals, as long as they do not coordinate with candidates. We will discuss the role of interest group related PACs and Super-PACs below.

Classifying Interest Groups

Unsurprisingly., political scientists disagree over how to classify interest groups. However, one common way to classify the kinds of interest groups is to separate groups that aim at achieving their own economic or material interests—we will call these economic interest groups—and groups that are more concerned with policy outcomes that do not affect their own wealth, but aim instead to shape public policy in ways that will serve the public interest. These groups are often referred to as public interest groups. In between economic interests and public interest groups are “mass membership groups” that seek to shape public policy to serve the interests of relatively large segments of the public. As we can see in the following table on interest group campaign expenditures, the interest groups which are most actively engaged in electoral politics are often those who focus on the economic interests of their members.14

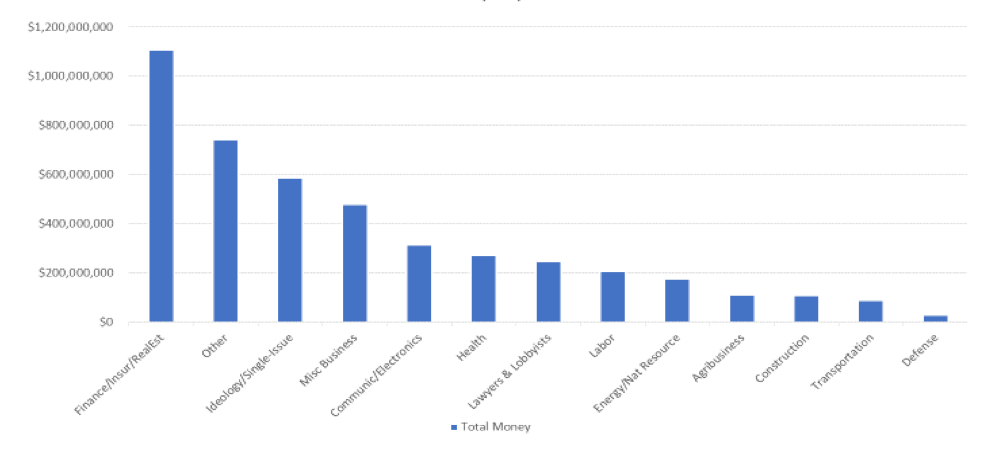

Figure 9.1: Interest Group Expenditures15

This graph is dominated by interest groups that are primarily concerned with pursuing their own economic interests—the financial industry, the legal profession, labour unions, and various industries whose fortunes depend upon government action. Note as well that the category of “other groups” is dominated by civil servants, educators, and retirees—and we can assume that these interest groups aim to protect the economic interests of their members, just as the construction industry and defense industry lobby out of economic self-interests.

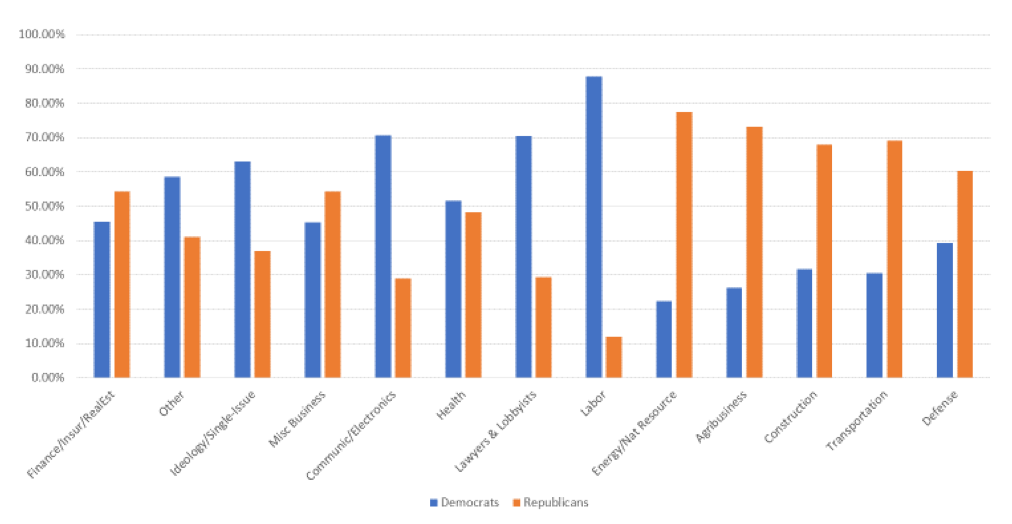

We should also note that the patterns of political donations of these interest groups reflect the differing orientations of the major political parties. Public sector groups, environmental groups, labor unions, and the legal profession favour the Democratic party. Industries involved in resource extraction, defense, and transportation favour the Republican party. It is also interesting to note that some of the most powerful types of interest groups are close to being “non-partisan,” in that they spread their economic resources equally between the two major parties.16

Figure 9.2: Interest Group Political Donations

Economic Interests

Many interest groups organize to increase the wealth of the industries, professions, and workers that they represent. For reasons having to do with the problems of forming interest group organizations, these groups have long dominated the “interest group environment,” not only in Washington D.C., but in many state capitals as well. Economic interests can be subdivided according the kinds of interest involved: business or manufacturing interests, professional interests, agricultural interests, and labor unions.

Business Interests

Public policy can shape the fortunes of all sectors of the private economy, and thus businesses of all kinds organize to influence public policy. Some businesses are large enough to finance their own interest group activity. For instance, the health care company Blue Cross/Blue Shield spent over $25 million on lobbying in 2016; other individual corporations such as Exxon and Amazon spent more than $10 million on lobbying. Other businesses work together in various kinds of trade associations which advocate for industry-specific issues; some of the major trade associations include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Realtors, and the American Hospital Association.

While one might assume that business interests would prefer the supposedly “pro-business” party—the Republicans—political donations from business interests are in many cases spread across the political spectrum. There are several reasons for this. On the one hand, some business interests may prefer the policy approach of Democrats. For instance, Silicon Valley technology firms may have shifted towards the Democratic Party between 2008 and 2016, as these firms (and perhaps their employees) benefit from relatively open immigration policies that increase the supply of workers, whether skilled or un-skilled. On the other hand, many business interests wish to maintain influence with both parties, regardless of the results of elections. Thus, the real estate sector provides support to both parties in relatively equal amounts.

Professional Associations

Professional associations represent individual practitioners in various fields which (usually) require specialized expertise or training of some kind. The American Medical Association and the American Trial Lawyer’s Association are two of the most prominent professional associations, and their patterns of support reflect some of the same dynamics as those of business associations. The American Medical Association has traditionally been associated with the Republican party, for the simple reason that most doctors in the United States are skeptical about government control of health care. However, the American Medical Association is not rigidly partisan; it attempts to support the Democratic Party as well. The American Trial Lawyer’s Association is an example of a much more partisan professional association. At both the federal and state level, Republicans support laws that would restrict class action lawsuits against manufacturers, businesses, state and local governments, doctors, and so on. On issues that affect the wealth, status, and power of trial lawyers, the parties are distinct, and thus American trial lawyers provide the vast bulk of their support to the Democrats.

Agricultural Interests

Agriculture is just another economic activity, yet in American political rhetoric and American political science, farmers have been placed in a separate category from other types of businesses and professions. This is probably because, at least since the time of Thomas Jefferson, farmers have been regarded as uniquely virtuous, and uniquely suited to the virtues of citizenship in a democratic republic. Some of the most significant social movements in the later 19th century were associated with “agrarian radicalism”— the belief, widespread in the mid-west, mountain west, and south, that national economic policies favoured the interests of the industrializing east, as well as the railroad industry and banking interests. The Populist movement, rooted in the discontent of the agricultural regions of the nation, led to the creation of one of the most significant “third party” movements in American political history; under the leadership of William Jennings Bryan, agrarian radicalism captured the Democratic party in the electoral campaign of 1896. Economic prosperity and rising agricultural prices in the early party of the 20th century limited the appeal of agrarian radicalism, yet the Great Depression led to new government activism on behalf of agricultural interests, and the development of highly organized, often sector specific agricultural interest groups. Today, these groups are particularly influential, despite the declining percentage of the American population that works in the agricultural sector.17

Labour Unions

Federal and state laws shape the ability of unions to organize their members and to influence labour-management relations. As a result, unions have a strong interest in maintaining interest group organizations to press their claims. Private sector labour unions have declined in numbers and power over the course of the past half century, but public sector labour unions remain a significant political force. In many cases, the most powerful labour union are public sector unions such as teachers’ unions. These groups may not wield irresistible force at the national level, but they are often able to exert considerable influence in state and local elections.

Intergovernmental Organizations

It might seem strange to suggest that governments can themselves be interest groups. Yet given the massive increase in federal spending that shapes many aspects of public policy, state and local governments, and even state bureaucracies, have an incentive to organize as interest groups in order to shape politics in Washington. Some of the most important inter-governmental groups include the National Governor’s Association, The National Conference of State Legislatures, and the National League of Cities; there are even interest group organizations that represent the interests of state-level bureaucrats, such as the National Association of Clean Water Agencies.

Table 9.1: Overview of Economic Interest Groups

| Type of Interest | Key Organizations | Key Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Business | US. Chamber of Commerce American Association of Manufacturers |

Limit taxes and regulations that affect business, while maintaining subsidies, trade barriers, and tax exemptions that benefit business |

| Agriculture | American Farm Bureau Federation Product-specific Organizations |

Maintain subsidies and trade barriers that support the agricultural sector |

| Professional | American Medical Association American Trial Lawyers Association | Maintain special legal privileges, policies, and forms of public spending that enhance the prestige and wealth of the profession |

| Labour | AFL-CIO National Education Association SEIU |

Maintain and advance laws that enable unionization in the private and public sector |

| Intergovernmental | National Governors Association National League of Cities |

Maintain federal spending in areas that affect state and local policy Limit federal authority to determine the content of policy |

Public Interest Groups, Citizen Groups, and Policy-Oriented Organizations

Public interest groups, rather than trying to achieve benefits for their members such as increased spending on public schools, increased legal protections for organized labour, or decreased regulatory burdens for the oil industry, instead try to alter law and policy for the public as a whole (or at least broad sectors of the public.) Public interest groups or citizen groups often aim to help individuals who are not actually members or even direct supporters of the groups themselves. Stated somewhat differently, public interest groups attempt to achieve “collective goods” (benefits that accrue to non-members) as opposed to “selective goods” or “private good” (benefits that only accrue to group members.)

Public interest groups are related to, but conceptually distinct from, the political phenomena known as “social movements.” Social movements refer to relatively large groups of like-minded individuals who are united in a shared belief about some aspect of public policy. The key difference between social movements and interest groups is that social movements are relatively informal—one can consider oneself a member of the gay rights movement without necessarily being directly involved with the groups that mobilize voters, lobby, and litigate on behalf of gay rights. Some of the most important social movements in the United States include the abolitionist movement of the mid-19th century, the prohibition movement of the early 20th century, the feminist movement of both the early and late 20th century, the civil rights and indigenous rights movement, the environmental and consumer rights movement, and the Christian evangelical movement. The list could be expanded further. In most of these cases, the movements spawned interest group organizations—organizations that continued to operate even as the enthusiasm for the movement declined. In many cases, social movements mobilize in response to in response to high profile events, events that generate intense public emotion and widespread political action. Interest groups can be understood as attempts to “institutionalize” the modes of political protest associated with social movements, though it is important to note that some interest groups organizations exist prior to the emergence of social movements. Thus the tactics of social movements often differ from those of interest groups. Many interest groups exercise influence through a combination of access to and influence over politicians. New social movements, which often form because they have been excluded from mainstream politics, often engage in various forms of contentious politics, such as the street protests associated with the anti-war movement of the 1960s or the Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter movements which emerged over the last decade.

Varieties of Public Interest and Citizen Groups

Civil Rights Organizations- Racial and Ethnic Minorities, GLBT, : Civil rights organizations attempt to defend the rights and interests of groups that have been excluded from full participation in the American political order. While all interest groups face problems with internal divisions, civil rights organizations have often featured particularly intense conflict amongst their members and leaders over the goals, strategies, and tactics of the organization. For instance, for many years the NAACP18 national leadership focused on providing expert assistance to local organizations concerned with police abuse, vigilante attacks on African Amerians, restrictions on voting and property rights, and racial discrimination in housing, employment, and labour unions. Many members of the civil rights movement objected to the NAACP’s focus on concrete short-term goals, advocating instead for alliances with other groups that had more radical objectives. The reasons for the deep tensions within some civil rights groups are not difficult to discern. Many interest groups represent established members of society that simply want to improve their own position within the community; civil rights groups represent individuals who have been excluded from full participation within society, which can generate both the desire for inclusion and an adversarial attitude towards the broader society.19 As in the case of labor unions (which, at one point, often featured large numbers of revolutionary communists), civil rights organizations representing groups such as African Americans, Latinos/latinas, and the GLBT community have become more moderate over time; rather than trying to transform society as a whole, interest groups representing these communities have become more like labor or professional organizations, seeking particular reforms or protecting reforms that have already been achieved.20

Environmental and Consumer Groups: Probably the best example of “public interest” groups are environmental and consumer groups- and this is true even if you do not share the programmatic goals and political assumptions of either movement. This is because these groups aim to achieve goods that they assume will benefit all of society, not merely members of the group or a sub-set of society. Environmental and consumer groups lobby legislatures on questions related to environmental policy, conduct litigation campaigns, attempt to educate the public about environmental issues, and mobilize the public to support pro-environmental candidates. Consumer groups engage in similar activities, though over time those groups have become less significant (in terms of size and resources) than groups within the environmental movement. In terms of lobbying expenditures, for example, environmental groups spent significantly more ($17 million in 2017) than gun rights organizations ($10 million.)21

Feminist Interest Groups: Women have organized various political organizations throughout American history. Some of the most prominent organizations include the League of Women Voters, which was organized originally to secure women the right to vote, and has continued as an advocacy group up until the present day. In contrast with environmental interest groups, feminist organizations (or, more broadly, women’s organizations) strive for a broader array of goals. Some women’s organizations are closer to professional associations than to activist civil rights groups (e.g. the Federation of Business and Professional Women, U.S. Women’s Chamber of Commerce.) Groups like the National Organization for Women (NOW) and the National Association for Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) pursue goals that are more closely associated with the feminist movement. One of the more prominent feminist-leaning political organizations in the United States is EMILY’s List, a political action committee that works to elect pro-choice female candidates.22 EMILY’s List gave close to 8 million dollars to candidates in the 2016 election cycle. Even more impressively, the PAC spent 33 million on “outside spending” (election-related communications and advertisements) which was more than the amount spent by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Policy Oriented Groups : A large number of groups exist to promote policies that are of concern to specific sub-set of the population. Of course, many of the supporters of these groups would argue that the policies they promote benefit everyone, as environmentalists assume to be the case for the issues that concern them. Nevertheless, groups such as the National Rifle Association and the American Association of Retired People are more concerned with the “intense preferences” of their members (to limit gun control laws; to prevent reform of Medicare and Social Security) than they are with the concerns of the broader public.

As we can see from this discussion, the concept of interest groups is rather fluid. Political scientist Matt Grossman suggests that we can think about interest groups by seeing them in three different dimensions:

- Groups Basis: Interest groups are rooted in different constituencies in society, though the scope and size of that constituency will often vary. The relevant constituencies can be defined by social characteristics, opinions, or economic interests.

- Organizational Basis: The actual organizations that represent the interest groups (e.g. the National Rifle Association for gun-owners, the American Association for Retired People for the elderly, etc.

- Political Affiliation: the parties and politicians who are most closely affiliated with the interest group constituency and organization.

Table 9.2: Overview of Public Interest and Citizen Groups

| Interest Type | Key Organizations | Policy Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Civil Rights | NAACP GLAAD |

Expand rights protections for minority groups; protect and expand policies that protect those groups |

| Environmental and Consumer Groups | Sierra Club | Defend existing environmental and consumer protections; advocate for more extensive regulations |

| Feminist/Women’s Organizations | NOW NARAL EMILY’s List |

Varies by group- in general, promote women’s rights and female political candidates |

| Other Policy-Oriented Groups | National Rifle Association American Association of Retired People |

Varies by Issue |

III. How do interest groups form?↑

While interest group spending is not always equivalent to interest group power or influence, patterns of interest group spending today support conclusions that political scientists have been making for close to a century—that the interest group “chorus” seems to sing with an “upper class accent.” The groups that are most active in politics—at least in terms of activity in the electoral arena— often appear to be groups that are motivated by the interests of specific professional groups and industries. Mass membership organizations that are not tied to specific economic interests seem more difficult to create and more difficult to maintain. But why is this the case? Is it actually the case? Is it true that some kinds of interests are more likely to form interest groups? Questions about interest group formation are not only theoretical. Our answers to these questions will shape our understanding of the relationship between interest groups and democracy.

Individuals who create political organizations of almost kind must be willing to expend time, effort, and economic resources, and in some cases risk their own personal safety. The chance of achieving success is uncertain at best, and in many cases the founders of even successful interest groups are unlikely to live to see their wishes come to fulfillment. In other words, it is impossible (or at best very difficult) to understand the creators or founders of interest group organizations as being motivated by rational economic self-interest alone. The motives of these political entrepreneurs must be understood differently.

Political entrepreneurs, much like economic entrepreneurs, seem to differ from ordinary citizens in several crucial ways. To begin with, entrepreneurs of all kinds are likely to have very long “time horizons”: they are willing to expend resources in the present, in the hopes of achieving long-term goals. This also requires individuals to defer gratification, accept hardships and setbacks, and to not be deterred by apparent failures. Entrepreneurs have to be exceptionally resilient. In some ways, entrepreneurs have to be irrational—they must have a very high, perhaps even unrealistic assessment of their own efficacy, in order to ignore or overcome the obstacles to success. A purely rational, self-interested individual, aware of the difficulties of political organization or the difficulties of starting a new business, would be more likely to restrict themselves to pedestrian forms of political activity—or to seek out employment in a large, stable, bureaucratic organization. Perhaps most importantly, political entrepreneurs are often motivated by the allure of ideas as opposed to the allure of wealth and status. Political entrepreneurs possess rare intellectual abilities and character traits; they could more easily achieve success by applying themselves to more ordinary pursuits. That they choose not to is simply a sign that ordinary forms of achievement are not always attractive to exceptional individuals.

If we examine the origins of most major interest groups, we can usually find examples of political entrepreneurs who are willing to sacrifice short term self-interest in favour of commitment to some vision of how the world should be.23 Consider the example of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP. The NAACP was formed in 1909; prior to this time, there was no national organization that was capable of lobbying or litigating to protect the rights of African Americans. African Americans certainly had a shared interest in organizing to advance their interests, yet the mere existence of shared interests amongst a group does not mean that the group will always develop interest group organizations to represent them, particularly if the group is large and relatively poor. The creation of the NAACP in 1909 was the result of the decision of a relatively small number of individuals to bear the burdens of political organization, in the hopes of achieving benefits over the very long term.

Is it possible to say anything systematic about interest group formation, given that the creation of interest groups seems to depend upon the decisions of a relatively small number of individuals, and is therefore subject to a variety of idiosyncratic factors? It is true that the timing of interest group formation is not likely to be a consequence of the conditions of the group. African American would have benefitted from the NAACP at any point during the half century between the Civil War and 1909, and there is little evidence to support the idea that conditions had become worse in 1909, as opposed to the 1870s, 1880s, or 1890s. The formation of any particular interest group is not something that can be explained with any degree of precision. However, it does seem to be the case that interest group formation seems to occur in waves, with some periods of American history witnessing the creation of large numbers of interest groups. In the past hundred years, political scientists have identified the first two decades of the twentieth century and the 1960s as eras of rapid interest group growth. The question is why interest group creation seems to occur in spurts or explosions, as opposed to following a steadier pattern of development.

There is no agreed upon answer to the question of why some eras or decades exhibit a greater degree of interest group creation. One theory is that interest group formation occur as a response to the excesses of already established interest groups.24 The late 19th century, often referred to as the “Gilded Age,” is well known for the close relationship between big business and government, at both the national and state level.25 While the scope of American government had changed immensely by the 1960s, big corporations had learned to accommodate themselves to big government. In both decades, social movements emerged to contest the policy status quo, which appeared to grant an advantage to established elites at the expense of the public. Finally, some scholars have noted that interest group formation depends upon the existence of “organizational cadres,” individuals who have the time, inclination, and capacity to engage in political organization. As higher education expanded, significantly in the first decades of the 20th century, and dramatically in the post-WW II era, the number of people with the capacity to develop interest group organizations expanded as well.

Building Interest Groups: Collective Action, Free Riders, Selective Incentives

While the creation of interest groups by cadres of political entrepreneurs cannot be understood as a consequence of rational economic self-interest alone, the development, maintenance, and institutionalization of interest groups can be illuminated if we start with the assumption that human beings act on the basis of rational self-interest. According to pluralist theories, interest groups form in an almost spontaneous manner, based upon the desire of individuals to advance their collective interests. The various groups in society will either generate their own organizations, and if they do not, elected officials and elites will still take into account the interests of the unorganized. In other words, pluralists tended to regard interest group organization as something that was relatively unproblematic—interest groups simply coalesced , and even if they did not, elites have incentives to take into account the inchoate desires of the various groups in society that lack organized representation.26 According to the “economic” or “transaction” theory of interest groups, the collection of organized interest groups will not be representative of society as a whole, due to the simple fact that individuals who have shared interests might not always have an incentive to act together in order to achieve those interests. For instance, in his book The Logic of Collective Action, the economist Mancur Olson attempted to explain why only certain types of “interests” tend to be represented by organized interest groups. Olson argued that groups of individuals who have some shared interest will not necessarily act together to advance or protect those interests. The failure of individuals to work together to achieve a mutually beneficial goal is known as a collective action problem. A collective action problem exists whenever a group of individuals would benefit from cooperating, but they fail to cooperate due to the incentive to defect or “free ride.” Consider the example of a group of messy university roommates. All of them would benefit from having a clean apartment, but collaboration proves to be difficult– they all secretly hope to “free ride” off of the person who has the least tolerance for dirt and disorder.

Another way to think of the collective action problem is to think of it in terms of public goods, the relationship between the individual and the state, and the compulsory nature of taxation A public good is a good that is non-excludable— if these goods are to be enjoyed by anyone, they will be enjoyed by everyone. National defense, clean air, and public roads are all examples of public goods: if a government provides these things at all, then it will (more or less) provide them to everyone. Given that public goods are non-excludable by definition, they typically will only exist at all if provided for by means of compulsory taxation. Imagine that our contribution to the defense budget was voluntary (or our contributions to the enforcement of environmental law.) While some people would still donate money to these causes, out of sense of duty or generosity, it is almost certainly the cases that the military or environmental policy would be underfunded if they had to rely upon voluntary donations. Under a voluntary tax payment system, individuals would have an incentive to not pay their share, and thus to “free ride” on the contributions of others, because their tax liability will not affect the provision of the good (their contribution is trivial) and because everyone will benefit from the provision of the good if it is provided, regardless of how much they paid to support it (the good is non-excludable.) Thus, the voluntary tax payer could obtain the benefit of the good without paying the costs (end thereby enjoy being a “free rider.”) This helps to explain why, wherever you go, taxation is compulsory; governments do not usually rely on the kindness of strangers to provide public goods.

What does this have to do with interest groups? Many interest groups try to provide non-excludable goods for their members. For instance, the environmental policies preferred by the Sierra Club will affect society as a whole, not simply the supporters of the Sierra Club. Yet interest groups (with some notable exceptions) cannot force individuals to contribute to their cause. The implication is that large numbers of “interests” in society will not be represented in the “interest group environment.” Why is it particularly difficult to get large groups of individuals to cooperate to achieve a shared political goal? Whereas small groups (such as roommates) have various tools that can be used to facilitate collective action (e.g. public shaming), mass “interests” are largely anonymous and decentralized. There is often no easy way to coerce those who prefer to free ride. Collective action problems can be overcome when the relevant individuals are aware that failure to collaborate will make it impossible to achieve the goal—that is, collective action problems can be overcome if the “trivial contribution problem” is overcome. However, in most circumstances, interest groups will depend upon support from thousands and thousands of individuals—and they are likely to be aware that their own contributions will not affect the overall success or failure of the interest group.

The perspective on interest group formation that we have just described is based upon individual economic rationality. It helps us to understand some of the reasons why “interests” that exist in society might not be represented by interest groups—if we assume that individuals tend to act on the basis on individual economic self-interest, then collective action in pursuit of non-excludable goods will be difficult to sustain. If this perspective is true—if it is best to understand the mobilization of interests in terms of problems of individual incentives—then we would expect that the “interest group environment” will not be representative of society; we would expect that “power elite” theories would be closer to the truth than theories of pluralism. Groups that are relatively small (where the contributions of individual “members” might not be non-trivial) have an advantage in terms of political organization: Firms within specific industries might be the best example here. Groups that are able to impose coercive measures in some way (for instance, labour unions and professional associations) will also have an advantage. In other words, if we assume that individual self-interest is the primary motivating force in politics, we will also predict that the “interest group environment” will be unrepresentative of the public.

There are many possible responses to the theory of collective action and “free riding,” as it does not seem to account for some of the most important examples of public political mobilization in American political history. In particular, the theory cannot account for the massive social movements that have periodically emerged in American political life. In the 19th century, movements for the abolition of slavery and prohibition of alcohol, to name only two of the most prominent examples, were sustained by the actions of hundreds of thousands of activists and volunteers. By the late 19th century, hundreds of thousands of farmers joined various radical agrarian movements, in the hopes of challenging the structure of the American economy as a whole. Similar social movements developed in the mid-to-late twentieth century—the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, as well as movements associated with the rights of sexual and racial minorities. The very existence of mass social movements suggests that there are limits to the theory of collective action—at the very least, people are often willing to sacrifice time, resources, and perhaps even their personal safety, even in situations where they have an incentive to be “free riders.” Yet even if the collective action problem framework cannot explain all aspects of interest group formation, it remains useful as a starting point for reflection on interest group activity. In some instances, the collective action problem is overcome. What are those circumstances? And have those circumstances become more common over time.

Overcoming the Collective Action Problem: The Role of Incentives

How do interest groups overcome the incentive to “free ride”– the incentive to let other people take up the burden of political organization? The short answer is this: interest groups, and political organizations of all kinds, require some means to force individuals to support them, or they must rely upon different kinds of incentives to encourage individuals to provide support voluntarily.

The incentives can take different forms. Interest groups often provide material incentives— tangible goods and services–in order to encourage potential members to support them. Oneclassic example of material incentives for political organizations is the use of patronage by political machines. Solidary incentives refer to the joys of belonging— the honors, offices, and respect that individuals can acquire by being participating members of organized interest groups. Solidary benefits can also involve the general pleasures of group experience: fun, comradeship, and mutual self-esteem. In the early history of labour unions, for instance, the social benefits of union participation was often as important as economic incentives. Purposive incentives refer to the ideological reasons for joining a group.27

Many interest groups rely on all of these incentives to promote group membership. Consider the example of an individual gun-owner: why shouldn’t they just sit at home with their anti-tank weapons, and benefit from the political activism of the NRA? The answer is that the NRA gives individuals many specific reasons to join the organization. In terms of material incentives, $40 gets you a magazine, a cap, travel and auto discounts, a Visa card, and access to information about gun related activities. In terms of solidary incentives, various awards and honours are given to individual members (e.g. awards for devotion to the organization, or awards for marksmanship); various competitions and meetings promote collective solidarity as well. In terms of purposive incentives, the NRA articulates its ideological goals in clear and precise terms, and connects gun-related issues with broader political-cultural memes. Individual economic rationality creates a kind of barrier to interest group formation—but those barriers can be overcome.28

The contemporary “Black Lives Matter” organization illustrates the role played by all three types of incentives. The underlying concerns of BLM movement—racism in American society in general, police brutality in particular— are hardly novel. A series of widely reported incidents in which young black men were killed by whites (or “white Hispanic”) citizens and police officers increased the salience of these issues, making it easier for political entrepreneurs to use “purposive incentives” to build their organization. Social media allowed individuals to spread their own perceptions and interpretations of the killings that occurred over the period between 2012 and 2015, raising the salience of the issues even further. Individuals who participate in the movement’s protest activities testify to the bonds of friendship and solidarity that they have forged through participation in the movement. The question of whether of whether material incentives play a role in the Black Lives Matter movement is more difficult to determine. The Black Lives Matter movement certainly does not offer special insurance benefits to its members, as in the case of the AARP or the NRA. It may be the case that material incentives of that kind are no longer as necessary to promote membership in this movement. New forms of communication have enabled individuals to raise money on line in order to fund their protest activities; many of the movement’s leaders and organizers are upper-middle class and university educated, and are thus more likely to act on the basis of purely purposive or solidaristic motives. Yet the Black Lives Matter movement has also been sustained by interest group organizations that have well-developed revenue streams, and the movement has been able to attract outside funding as well. The Black Lives Matter movement, upon closer inspection, is sustained by alliances amongst a wide variety of smaller, more organized interest group organizations that receive support from private foundations and donors. Thus, material incentives play a role in interest group formation and participation, just as the use of political patronage in the 19th century gave individuals and incentive to become active party members.

Interest groups attempt to mobilize supporters through material, solidary, and purposive incentives, and this suggests that the “collective action problem,” rooted in the notion that human beings are motivated by rational self-interest, is a real obstacle to interest group formation, albeit one that can be overcome. However, other thinkers have argued that sociological differences between various groups in society can help to explain the success or failure of interest group formation. This approach can be labelled the “socio-political capital” theory of interest group formation. Socio-political capital refers to the capacity of individuals to engage in cooperative endeavours—this might involve some combination of cultural traits, skills, and traditions that enable people to work together for common ends. Groups that share similar economic traits—such as income—might differ because of differences in social capital. Consider the differences between engineers and lawyers. Both groups are part of the socio-economic elite—they are highly educated, and relatively wealthy—yet lawyer’s organizations have been far more active, and arguably more successful, at all levels of American government. We will return to the question of why different kinds of groups experience different levels of effectiveness in interest representation below, in the discussion of interest group power.

Political Participation and the Emergence of Modern Interest Group Politics

Why have interest groups have become more significant as a way of channeling political participation? Given other ways of engaging in politics, what explains the expansion of interest group politics (e.g. the formation of lobbying groups, as well as electoral groups that do not attempt to control the institutions of government directly.) To understand the role of interest groups in American politics, we should think of interest group activity as an alternative to party politics. They are both differing modes of public participation, and while they admittedly overlap, they are distinct in important ways. There are surely other aspects of political participation that we could discuss, but I want to focus on the development of citizenship and its relationship to interest group politics. The story that most political scientists tell about citizenship is one of decline—the rise of interest group politics came at the expense of broader citizen participation, in the sense that parties have almost always been better at mobilizing citizens to engage in politics, at the very least through voting. However, recent developments in American politics suggest that citizenship, understood as active engagement in political life, is in many ways on the upswing in American politics– the best examples of this are first, the coalition of citizens who helped bring Barak Obama to office in 2008, the Tea Party movement which had a decisive impact on American politics in 2010, the Occupy Movement of 2011, the Black Lives Matter movement, and even the unexpected populist uprising that brought Donald Trump the Presidency. But first, let’s try to see if we can follow the narrative of decline; “the descent of American citizenship” and the rise of interest group politics.

The Partisan Era

The golden era of public participation in politics occurred in the 19th century, when political activity was closely associated with political parties.29 Partisanship was a major aspect of social life: e.g. “mass media” was partisan; political activity was a kind of entertainment; most importantly, political participation was close to ubiquitous for white male citizens. Obviously, this era of broad public participation coincided with a race-based caste system, -gender bias, and the exclusion of many ideological issues. Mass political participation also did little to prevent corruption. At the same time, the party system could be subject to serious challenge by broad based “social movements,” such as the abolitionist movement, the populist movement, or the temperance movement. This era of public participation came to an end, however, as progressive elites started to challenge the basis of party politics.

Various progressive era reforms reduced the power of political parties: primaries reduced the power of party elites; direct election of senators reduced the significance of state party organizations; state government adopted many elements of direct democracy, in order to strengthen direct link between governments and citizen: initiatives (a law proposed to the voters of a state through petition,) referenda (appeal to the public for approval of a piece of legislation,) and recall elections (a new election for an official prior to end of their term) were the most notable institutional innovations. The power of political parties was also affected by the rise of independent media—journalists who were not tied to particular parties, but who instead attempted to provide objective information about social and political life. Interest group organizations started to provide new types of information to voters and popularize new issues. 30Professionalized bureaucracies reduced the ability of parties to rely on patronage. The progressive era did not lead to the destruction of parties, but it started to change the institutional environment, making “parties” less attractive as a site for political participation.

The rise of interest group politics was preceded by an era of mass political participation, such as the Civil Rights Movement, and the closely connected anti-war movement. The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and the 1960s was in many ways the epitome of active and effective citizenship. Mass mobilization disrupted the political status quo, forcing changes through both litigation and political pressure. This lead to changed constitutional doctrines, new legislation to address various aspects of racial discrimination, as well as the bureaucratic machinery to implement those decisions. We should also note that while the successes of the “civil rights movement” were most apparent by the 1960s, the interest group organizations who initiated the movement had to toil in (relative) obscurity for a generation or more.

However, the civil rights era did not lead to an era of increased public participation; it certainly did not lead the public to become more engaged with political parties. The post-1960s era saw increased dissatisfaction with the established parties, or at least decreased partisanship. The public became less engaged politically in some ways (e.g. in regards to voting rates) In other ways the political system was more “participatory” than ever before, as new interest groups emerged, and older interest groups developed their capacities. These new interest groups included consumer groups, new civil rights organizations, environmentalist groups, children’s advocates, disability groups, feminist organizations, and so on. Why did this explosion in interest groups occur? What was changing? Why, in many instances, did new political issues lead to the creation of new organizations?

The Interest Group Explosion

During the mid-20th century, the interest group environment was relatively moribund, organized national interest groups included labor groups, business organizations, some professions (such as the American Medical Association), and little else. Yet as the political environment changed, it became easier for other types of interests to develop organizational representation as well. The following factors seem likely to have contributed to the “interest group explosion” of the second half of the twentieth century.

The Size of Government: The growth of the American national state precedes the expansion of interest groups, and there are reasons to think that the growth of the state encouraged the growth of interest group organizations. Consider the examples of recipient groups (groups that receive direct benefits from government): once a group becomes a beneficiary of government largesse, it will be easier to organize that group to protect their benefits. Today, one of the principal aims of the the AARP (American Association of Retired People) is to protect social security benefits, but it did not organized to create those benefits. It is simply easier to mobilize people to defend a benefit that is already received, as opposed to organizing people to pursue an uncertain goal.

Service Delivery Groups are a slight variation on recipient groups. “SDGs” are not objects of government action, but are instead the people and institutions who benefit from the expansion of government policies because they play a major role implementing those policies. Institutions (including cities and states) organize to insure federal money keeps flowing. Teachers, social workers, and other public sector workers have particularly active national organizations. These organizations emerged after the federal government started to use federal grants to fund education and various social services at the state and local level.

Some groups emerge because government creates them through direct grants of money. Perhaps ironically, this applies to the NRA. Congress funded many aspects of the NRA in the early 20th century. The national government offers numerous grants to interest groups, who often organize to oppose government. Government action can also increase the incentives for interest group mobilization in an unintentional fashion. Supreme Court decisions related to abortion school prayer) mobilized evangelical Christians. A less serious example is the “Bass Master” organization; this group emerged only after federally funded dams created large numbers of lakes, which increased opportunities for bass fishing throughout the nation.

Affluence and Education: Americans became increasingly affluent and educated in the post-WWII era, and this had an effect on interest group politics. Between1942 and 1972, controlling for inflation, median family income doubled.Some thought this would decrease the level of political conflict; instead, conflict has become ubiquitous; new and conflicting demands emerged alongside increases in wealth. Why, contrary to the expectations of economic determinists of all stripes, did increasing affluence not reduce the scope of political conflict? Firstly,affluence creates a new mentality of demand, and less tolerance for less than ideal conditions. Secondly, in an affluent society, it iseasier for people to support interest groups; people have the luxury of caring about previously ignored issues (consumer safety, spotted owls, endangered slugs, etc.) In addition, affluence creates new forms of private political patronage– such as the Rockefeller, MacArthur, Ford and Gates foundations. Finally, one could make the argument that affluence creates new kinds of public problems—in particular, environmental problems.

The expansion of higher education contributed to the explosion of interest group activity as well. University education expanded the ranks of the “political class”—individuals trained journalism, religion, law, journalism, social work, in addition to the massive expansion of university instructors. These elites became the leaders of the new interest group organizations; they were the individuals most concerned with politics, and education gave them a greatest sense of personal efficacy, a perhaps a greatest conception of what aspects of the social order were likely to be altered. Once society is no longer seen as a natural object, but rather as an artificial construct that can be changed, then the scope of politics will increase; even the “personal” becomes “political.”

Technological Change: Finally, we should not forget that technological change helped to facilitate interest group politics. New technology dramatizes broader range of issues, makes it easier for groups to organize, solicit members. Technology made it easier to identify and communicate with members and potential members.

IV. What do Interest Groups do? American Institutions and Interest Group Strategies↑

Institutional Sources of Interest Group Power

American interest groups are much more numerous than interest groups in other nations, and there are reasons to think that this has institutional as opposed to cultural sources. For instance, in the United States, there are at least three major farm organizations, the largest of which is a federation of state and county associations; there are several veterans’ associations, and a host of business associations. In the United Kingdom, there is a single farm organization (The National Farmers’ Union) a single veteran’s organization, a dominant business association, and professional interests are usually national in focus (such as the British Medical Association.) Whether the greater proliferation of groups makes interest groups more powerful is a more difficult question to answer, but it is the case that interest groups in the USA seem to have greater potential to influence policy. This is because of the institutional environment which limits the power of political parties and creates opportunities for discretionary decision making. If individuals in Congress, in bureaucracies, in state and local government, and the courts, have discretion to make one decision rather than another, then interest groups can exercise influence.

There are four major institutional sources of interest group power in American politics:

1) TheSeparation of Powers: The system of partially separated powers leads to weak parties and (relatively) independent legislators; interest groups thus have greater ability in the American system to exercise influence through the legislative branch.

2) The delegation of legislative powerto the executive branch. Though delegation of legislative power occurs in parliamentary systems as well, American bureaucrats have to answer to both congressional and executive branch officials; the inability of the President to exercise uncontested control over the bureaucracy creates opportunities for interest groups to lobby bureaucratic decision makers.

3) Multiple, staggered elections Separate elections for the House, the Senate, and Presidency; combined with the primary system, all create opportunities for interest groups to influence the electoral process. Not all interest groups will be equally adept at shaping elections—in general, interest groups who are able to mobilize members as voters probably have more influence than interest groups who have access to financial resources. Interest groups are often most effective when they mobilize members to participate in low profile elections. For instance, school board elections are often shaped by the actions of teachers’ unions—low turnout, low salience elections, that can easily be affected by interest group activism.31

4) Courts Almost all elements of judicial power in the USA help to create opportunities for interest group influence: judicial review, changing notions of rights, statutory rights, changing legal standards (standing, remedial decree litigation, “torts,” fee shifting, as well as changing legal standards in administrative law.)

Interest Group Power and Elections

Interest group activities in elections rival the role played by parties, whether regarding fund raising, issue advertising, or voter mobilization. To understand the role played by interest groups in the electoral process, it is necessary to briefly outline the law of campaign finance regulation in the United States, and the ways in which it has shaped (or failed to shape) interest group activities in the electoral arena.

For close to a century and half, American elections and campaign donations were largely unregulated. The most important sources of campaign funding during much of this period came from party assessments—money that political parties collected from party members who had received government patronage positions. Towards the end of the 19th century, this began to change. Civil service laws made it more difficult for parties to raise money through the patronage system, but this gave parties an incentive to raise money from private parties. In particular, both Democrats and Republicans became more adept at extracting donations from large corporations, particularly those whose profits could be affected by public policy decisions at either the state or national level.

Congress responded to corporate influence by adopting the Tillman Act in 1907. This act banned direct donations from corporations to political candidates, though the law was relatively easy to evade. For instance, while monetary donations to campaigns were prohibited, “in-kind” donations (of various kinds of services and resources) were not. Thus, the Tillman Act, even if it had been strictly enforced, was not able to eliminate the links between corporations and political parties.

By the middle part of the twentieth century, legislators were also becoming concerned with the issue of labor unions in electoral politics. Both the Smith Conally Act of 1943 and the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 placed restrictions on the political activity of labor unions. In response, unions created new organizations that were not formally part of the union, organizations that would solicit contributions to donate money to election campaigns. These union-affiliated organizations cam to be known as “political action committees.” The development of these organizations by unions (and, eventually, by businesses, trade associations, ideological groups, etc.) illustrated a common them in the history of campaign finance: the attempt to restrict some kinds of interest group activity related to campaign spending tends to create alternative forms of organization, or alternative types of spending, that undercuts the aim of the law.

The next round of federal campaign finance reform in the 1970s attempted to place new limits on “arms length” political action committees associated with labor unions and corporations. The 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act required that all PAC donations be made public; subsequent amendments to FECA prohibited unions and corporations from making direct political donations to election campaigns. FECA also placed limits on the amount of money that PACs could donate to candidates (currently, $10,000 per election cycle.) However, PACs developed other mechanisms for exercising influence besides direct donations to candidates. Federal election law placed no limit on how much PACs could donate to state and local parties for “party building activities,” which included informational ads and “get out the vote drives.” The use of so-called “soft money” freed up the resources of parties and candidates to use in more directly political activities (such as ads that directly attacked other candidates, or called for the election of specific candidates.)

The “soft money” used by PACs led to the next stage of campaign finance law reform: the 2002 Bi-Partisan Campaign Finance Reform Act, or BCRA. This law placed new restrictions on the activities of PACs, but it suffered numerous challenges in the Supreme Court, usually on the grounds that the law placed unjustified limits on political activity and political speech. For instance, the BCRA placed limits on political advertisements prior to general elections and primary elections. Many of these restrictions were struck down by federal courts, including the Supreme Court. For instance, in the case of the Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right Life (2007), the Supreme Court ruled that the BCRA could not prevent political action committees from running issue-oriented ads in the days and weeks prior to elections. The most significant legal challenge to the BCRA occurred in the case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission 2010. In this 5-4 decisions, the Supreme Court ruled that all independent spending by unions and corporations was protected by the first amendment. This allowed union and corporations to use their own resources on campaign-related spending, instead of having to raise donations in smaller increments. The Citizens United decision thus led to the creation of “Super-PACs,” organizations that can raise unlimited amounts of money from individuals for election-related purposes, as long as they do not coordinate with political parties or individual candidates.

Interest group thus have several options when seeking to influence the electoral landscape. Political action committees can raise and “bundle” money for political candidates. “Super-PACs,” as “independent expenditure only” organizations, can now raise unlimited amounts of money to engage in electioneering activity (though they cannot donate to political candidates, and they cannot coordinate spending with candidates.) Interest groups can thus influence elections not only by donating money to candidates, but through information and mobilization– providing their members and the public with information about the votes and ideologies of various candidates. This has obviously become much cheaper in the age of social media. The ability to mobilize members– especially during low voter turnout elections– is probably an even more effective weapon than the ability to raise money.

One of the great puzzles in the study of interest group politics is whether interest group activity in elections shape the preferences of the elected officials, or whether interest groups simply support politicians who already advocate policies that they find congenial. For instance, is the Republican Party opposed to many climate change initiatives because it is supported by the natural resource industry? Or does the natural resources industry support the GOP because the party tends to be skeptical about climate change? One could ask similar questions about other major interest groups as well. Labor union interest groups are a crucial part of the Democratic party’s coalition, and this is particularly true for public sector unions such as teachers’ unions. Do the teachers’ unions dictate the Democratic party’s positions on education policy, or do the teachers’ unions provide support to the Democratic party because of the party tends to support a pro-teacher’s union (and anti-educational reform) agenda?32

Political scientists tend to reject the claim that interest group activity in elections, particularly campaign donations, directly changes how politicians vote.33 The purpose of interest group activity in elections is not to bribe politicians into doing things that they would not otherwise do. Rather, the main goal of interest groups is to help reshape the partisan agenda of Congress by changing who gets elected. Consider the example of EMILY’s list, a political action committee that is dedicated to electing pro-choice Democrats to Congress. EMILY’s List pioneered the practice of bundling, which simply means assembling donations from a wide variety of individuals and then passing on those donations to candidates. Bundling allows interest groups to promote their agenda by coordinating the political donations of large numbers of individuals. A large number of organized interest groups like EMILY’s List use their resources to help elect like-minded politicians, instead of attempting to shape the perspectives of politicians that they disagree with. A large percent of PAC money is given to “subsidize” friendly legislators, as opposed to trying to purchase the votes of politicians.34