Outline of the Chapter

- The Constitution and American Elections: The Separation of Powers

- American Political Parties and Party Systems: Ideas, Organization, Context

- The First Party System? Federalists versus Jeffersonian Democrats, from the Founding to the Era of Good Feelings (1790-1824)

- The Second Party System: Whigs vs. Democrats (1828-1854)

- Interlude: The Spatial Theory of Party Competition, Duverger’s Law, and the Role of Third Parties in American Political Development

- The Civil War and Reconstruction, The Gilded Age, and The Third Party System (1860-1894)

- The Fourth Party System: The Progressive/”Industrial Republican” Era (1896-1932)

- The Fifth Party System and The New Deal Coalition; From the Great Depression to the Great Society: 1932-1968

- The Sixth Party System? Political Parties, Elections, and the Era of Polarization 1968-2016

Learning Objectives

- Party Ideology and Party Coalitions:Explain the main differences between the major American political parties, in terms of their main political ideologies, the coalitions (groups of voters and interest groups) that have supported the parties, and the internal divisions within the parties. Most importantly, explain how the parties have changed over time.

- Party Organization:How do parties select candidates and mobilize supporters? How has this changed over time?

- The Concepts of Critical Elections/Re-Alignments and Electoral Alignments—Explain the relationship between critical elections, electoral re-alignment, and electoral alignment; what are some of the major objections to this way of thinking about party competition in American political history.

- The Spatial Theory of Party Competition:Explain the theory, and explain the extent to which it can account for party conflict in American elections.

- Explain how the Great Depression led to a “New Deal Coalition” in the Democratic Party; what were the main components of the coalition, and what were the major dividing lines within the coalition?

- Explain how party organizations started to change during the mid-20th century. Why was this significant?

- Explain why party polarization was in some ways an unexpected phenomena in American politics. What are some of the major explanations of why party polarization started to occur in the 1960s? Explain how the concept of “de-alignment” relates to the rise of party polarization.

I. The Constitution, American Elections, and The Separation of Powers↑

Political parties are a type of organization. Organizations are groups of individuals united by shared goals or tasks; while some organizations have relatively straightforward goals, the various goals of political parties are often in tension with one another. The central goal of most political parties in democratic societies is to achieve political power by winning elections. If your organization has no interest in running in elections at all, it might be an interest group, a club, or a revolutionary cult; but it is not a political party. In addition to the desire for political power, parties are motivated by ideas about the common good, and the various policies that will advance the common good. Party activists and leaders usually think these policy goals will serve the public interest, though it would not be excessively cynical to note that human beings have a tendency to conflate “the common good” with their own self-interest. Any given political party will contain a complex, ever-shifting balance between the desire for power and the desire to implement or defend certain policies. For instance, both the Canadian federal Conservative Party and the federal Liberal Party regard power as the ultimate desideratum, and thus the political ideologies and policy priorities of these parties tend to shift over time; the Green Party, in contrast, hopes to shift the public conversation about environmental policy—the Greens would like to win seats in Parliament, but they are not focussed on winning a parliamentary majority, or even on maximizing their own seats, but are instead motivated by the ideology of environmentalism. Thus, while all parties differ in how they balance the two competing considerations, they all face a tension between the connected but competing goals of power and policy. Stated differently, all parties are motivated by a mixture of interests and ideas.

The tension between the goals of “achieving power” and “implementing policy” has always been part of American political life, but it is particularly prominent in the contemporary political era. This is for a simple reason: party elites, defined broadly to include not only office holders, but also the most politically active elements of the public, are in some ways more divided by ideology than at any other period in American history. Yet in order to win elections, parties must still find ways to appeal to voters who may not share the same ideological priorities.

If we think about the increasing ideological divergence between party elites in the United States and elsewhere, we might be more sympathetic to those Framers who hoped that the power of parties could be limited by the structure of the Constitution. Obviously, whatever the hopes of the founding generation, the Constitution did not prevent political parties from becoming a crucial element of American politics. Yet even though the Constitution did not prevent parties from emerging, the Constitutional structure would shape how parties operate.

The Constitution influences how American political parties function in numerous ways, but no influence is more significant than the separate election of the President and the Congress. In the Canadian parliamentary system of government, citizens vote for members of the House of Commons— the Prime Minister is not elected by the votes of Canadian citizens in general, but is instead “chosen” by whichever party (or group of parties) is able to command a majority after a general election. Under most circumstances, the Prime Minister and his or her government can only maintain power if they are able to command the support of a majority of the House of Commons. This institutional feature of the Parliamentary system makes party discipline particularly significant in Canadian politics, as in all other parliamentary regimes.1 It is important to keep this simple fact in mind, in order to understand how institutions shape the character of political parties. While the power of the Prime Minister is based upon their ability to command majorities in the legislature, the American President’s tenure of office does not depend upon the support of the legislature2. Instead, the President is selected, for a defined term of office, through the votes of the “electoral college.” Under this system, every state in the Union is given a number of votes in the electoral college equal to its total number of Representatives and Senators in Congress. Whoever wins the largest number of votes3 in the electoral college becomes the President—and that person remains President until the next election, as long as they avoid being removed by Congress through the impeachment process, and as long as they avoid illness, death, and assassination.

This system of Presidential selection would have an enormous impact of on the organization of political parties. The American constitutional system, because it makes the chief executive independent of the legislative branch, makes party discipline far less significant in the American political order than in parliamentary systems. In particular, the institutional structure that separates the executive branch from the legislative branch makes American political parties, as organizations, more susceptible to public influence. Political parties in Canada are like private clubs and American political parties are more like public utilities, because in comparison with the Canadian public, the American public plays a far greater role in choosing candidates for political office. This has an important additional consequence: because the party system in the United States is relatively “open,” insurgent social forces have an incentive to channel ideological discontent into the existing party structures, as opposed to creating new political parties. As a result, American political parties have had a tendency, over time, to be more faction-ridden (or, if you prefer, they harbor more ideological diversity), whereas Canadian parties, relatively immune to direct popular control, have caused the discontented to form their own, alternative political organizations. Thus, while the “first past the post” electoral system that both countries share has the effect of reducing the number of viable parties, the Canadian system has had a three party (and even a “multi-party”) system for most of its existence. In contrast, the USA has had a mostly stable two party system for most of its political history. While some might claim that these differences are caused by sociological factors, the differences between Canadian and American institutions seems a far more likely explanation.

Let us consider the electoral college in more detail. Under the original Constitutional system of Presidential selection, the states were free to determine their “electors” in whatever manner they saw fit. Today most states assign electoral college votes based upon a “winner take all” popular election in the state as a whole; Maine and Nebraska assign electoral college votes based upon a district system. We should note that the electors in the electoral college were intended to be independent of the state governments, and even independent of state voters. Under the original system, states chose how the electors are selected, yet neither the states nor the people can legally constrain how the electors vote.4 From the Framers’ perspective, the general public lacked the kind of knowledge necessary to choose a suitable chief executive.5 But just as importantly, the Framers hoped that the President, by virtue of being selected by an independent group of (hopefully) respected and intelligent individuals, would be able to transcend the economic, regional, and cultural conflicts that would, of necessity, characterize Congressional politics. In other words, the President was to be both separate from and independent of “normal” politics; the Framers hoped the President would embody the common political interests of the nation as a whole, and that the President would regard his duty to the country and the Constitution to be more important that any attachment to a party or faction.

How do we know that the Framers of the Constitution expected the President to transcend ordinary political conflicts? Consider the original mode of selection for the Vice President: Article II, Section I, Paragraph 3: “The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed… after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice-President.” In other words, they did not think the contest for the Presidency would be partisan! The “loser” should be number 2 in line to the Presidency; had this practice been maintained, we would now have President Trump and Vice President Clinton.

The founders may have hoped that Presidents would rise above the disputes of politics in order to implement the law, unify the nation, and defend the Constitutional order, in a manner that would make the President more like a monarch or Chief Justice of the Supreme Court than a typical political operative. This proved to be impossible —the powers given to the President, particularly in the legislative process, made it very difficult for the President to transcend partisan political conflict. Furthermore, ideological differences emerged that could not be easily ameliorated through calm discussion and calculated bargaining. The hatred and heated passion that we associate with contemporary partisan politics was present from the beginning of the American Constitutional order, though we should also note that the strength of partisanship, or the “degree of political polarization” amongst elites and the public does wax and wane. The contentious period of the 1790s was followed by close to three decades of one-party dominance in American national politics. Though the nature of partisanship would change, the Presidency always remained politicized, contrary to the expectations of the Framers.

The notion that the Presidency and the Executive branch could transcend partisan squabbles was evident in the administration of President George Washington. Washington was spared the indignity of actually having to campaign for office due to the nearly universal reverence he received from Americans of all stations. In addition, Washington did not attempt to ally himself within any particular political faction, as can be seen in his selection of cabinet officials— the arch-Federalist Alexander Hamilton served as his Secretary of the Treasury, while Thomas Jefferson would serve as Washington’s secretary of state. Yet as ideological differences coalesced into clearer partisan factions over the course of the 1790s, the Presidency would not be able to transcend the political divisions of the nation.

II. American Political Parties and Party Systems: Ideas, Organization, Context↑

To understand political parties, we must consider the substantive goals they pursue, the means they use to pursue those goals, and the broader environment in which they operate. Stated differently, we need to consider ideas, organization, and “context” in order to understand parties. The relationship between parties and political ideology is of course complex; sometimes parties stand for a relatively coherent and even comprehensive set of principles, sometimes parties are composed of eclectic and even hostile factions, united by only a very narrow range of commitments; sometimes the major parties represent clear political alternatives, and sometimes the parties seem ideologically indistinct. Party organization has two key elements: the means of selecting candidates (an issue of crucial importance), and the means of recruiting and supporting the party elites who oversee the party organization and engage in the work of campaigning. Context is an imprecise concept, obviously; but for parties, context refers to the demographic features of their electoral supporters (where do their supporters come from? what voters are open to their appeals?), the means of communication that allow them to reach the voters (or acquire the resources necessary to mobilize and influence voters), and the other groups and organizations that attempt to shape public consciousness and the electoral process.

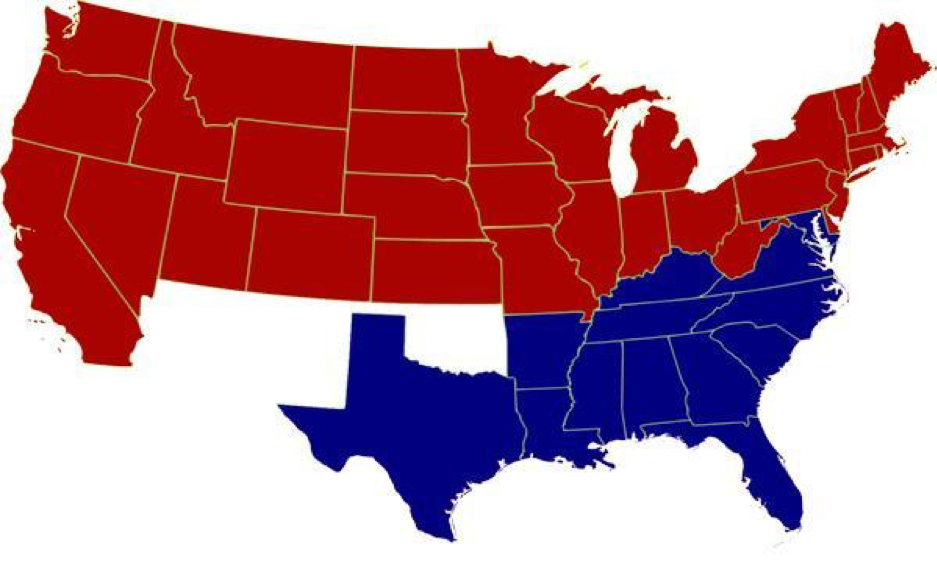

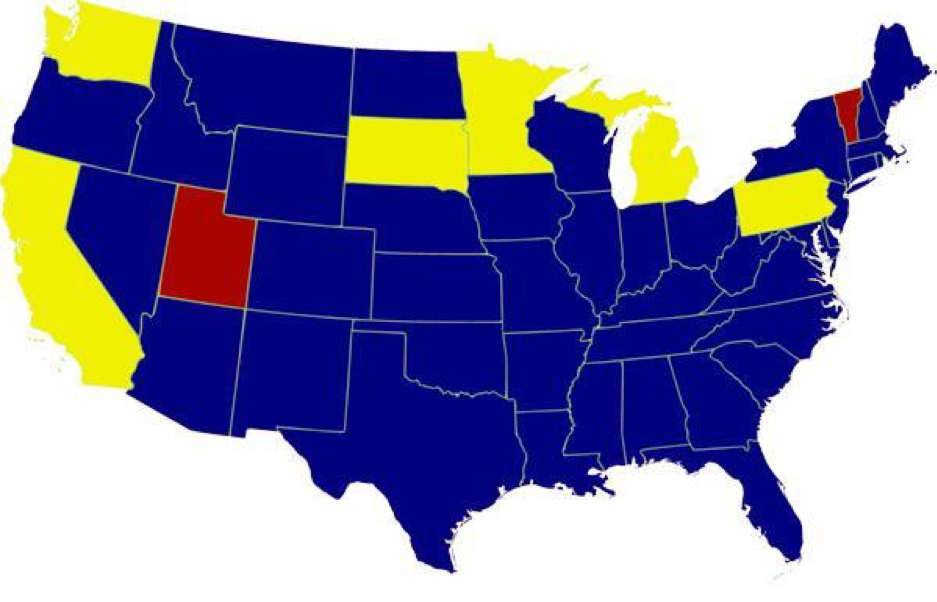

Over the course of American political history, the patterns of party ideology, organization, and “context” (e.g. the demographic-geographic patterns of party support, the main technologies of communication related to election campaigns, the role played by non-party groups and organizations in the electoral process) form a series of distinct periods or “alignments”—at least, this is one of the main ways of viewing the development of the American party system. The distinctions between periods are not always exact, and changes along some dimensions from one alignment to the next are not always stark—for instance, party coalitions change without corresponding changes in party ideology and party organization. By considering the differences between political alignments in American history, we can consider how the relatively unchanging institutional structure relates to the ever-changing character of American society.

Let us consider our three different perspectives on parties in a little more detail.

Party Systems (the Context of Political Conflict): Coalitions-Demographics-Regions-Strength

Parties can be considered from the perspective of their supporters—what kind of people typically support one party or another, whether in terms of race, ethnicity, sex? How does party support vary by region? Given the patterns of party support, what kinds of challenges do the parties face in managing and expanding their own electoral coalitions? Given the demographic-geographic components of party support, how much influence do short term factors— such as the state of the economy, the choices of political leaders, international events, and so on—have on electoral outcomes?

Party Organization: Candidate Selection, Communication Technology, Mode of Campaigning

The struggle to “democratize” the nomination process has been a central theme in the development of the American party system; in general, the power of parties (particularly party elites) to determine electoral candidates has declined, but each step in the reform process (from elite selection in the caucus system, to selection through the convention system, to the mixed system that characterized much of the 20th century, to the primary system that was only fully institutionalized at the national level by the 1970s) has created new sources of discontent. National party organization in the USA has evolved in four basic stages:

- The Patrician Era (First Party System): an early, elite-dominated process in which national officials played a major role in Presidential selection (from when the Constitution was adopted until approximately 1828) Political communication is relatively constricted, though an emerging partisan press is starting to reach a wider audience.

- The Jacksonian Model (Second and Third Party System): between the 1820s and approximately the 1880s, in which party organization was a “bottom-up” affair dominated by local and state party insiders. Political communication is dominated by a partisan press; political campaigning is raucous and “labour intensive,” characterized by mass public demonstrations and parades. Parties help maintain the support of “party regulars” through a system of government patronage.

- Late 19th and Early 20th Century (Fourth Party System): nationalizing trends enabled by new forms of communication technology are combined with individualizing trends (in particular, the direct primary election) which undercuts the influence of state and local party organizations. An independent press, characterized by official non-partisanship and professional journalistic standards, starts to play a more prominent role in campaigning. New forms of communication and technology (e.g. telegraphs and railroads) enable national candidates to conduct more ambitious political campaigns.

- Mid-Twentieth Century- Present (Fifth and Sixth Party Systems): Selection through party primaries is extended through all national offices, including the Presidency, by 1972. Party organization is to a large extent eclipsed by the role of individual campaign organizations and interest groups. New modes of communication create a post-modern mass media environment.

Table 4.1: Party Systems in the USA

| Era/ Major Parties | Party Ideology | Party Organization | Party Geography/Context | Transforming Crisis? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Party System Jeffersonian Era 1800-1824 | Republican-Democratic Party: “Individualist Egalitarianism” Federalists “Hierarchical Individualism” | Patrician Era—rudimentary organization, limited mobilization | Federalists are influential in NE/Mid-Atlantic; post-1800= “one party rule” | Rise of western frontier states, public mobilization, reaction against eastern elites (1824 election) |

| Second Party System: Jacksonian Era 1824-1852 | 6Democrats: Individualist Egalitarianism “Jeffersonian” Whigs: Hierarchical Individualism | Mass Politics State and Local orgs. predominate Campaigning | Both parties are competitive in most regions | Slavery ; third-party challenge |

| Third Party System: The Gilded Age 1860-1896 | Republicans: Hierarchical Individualist “Nationalism”Democrats: Jeffersonian | Continuity with Jacksonian Era Era of the “party machines” National party power emerges slowly | Electoral strength of the parties more or less even REGIONAL differences emerge: GOP rooted inNorth East and Mid-West, Democrats in South and West | Populist and Progressive challenge to established economic beliefs; thirdparty challenge fails, but decisively influences both parties |

| Fourth Party System: Industrial Republican/Progressive Era 1896-1932 | Republicans: Nationalist-Progressive Democrats: Populist-Progressive- Ascriptive Hierarchy | Transformative Era: direct primaries, independent press, campaign finance, mass media | (Complicated: regional patterns of support are quite volatile, outside of the Democrat-leaning “Solid South”) | The Great Depression |

| Fifth Party System: New Deal Coalition 1932-1968 ( | Democrats: Populist-Progressive Republicans: Neo-Liberal Moderates to New Right | Decline in party organizational strength Patronage channelled through the State Incumbency Advantage in Congress | The Democratic Party begins to move North. The GOP: complicated transformation as party shifts from moderate, north eastern base to “New Right” in the South, Mid-West, Plains, Mountain West | Civil Rights, Social Change, Vietnam and Foreign Policy |

| Sixth Party System: Divided Government/ New Republican Era 1968-2016? | Democrats: Progressive “Universalist” Republicans: Neo-conservative “New Right” | Candidate centered campaigning New Media Campaign Finance and “Capital Intensive” politics | Coast vs. Interior/South Cultural and Ethnic Divisions Religion Marriage Gap | Foreign Policy? Economic Policy? Courts and Cultural Issues? |

Party Ideology

Understanding party ideology in American politics is difficult, due to the simple fact that parties are often internally divided over ideological questions. Therefore, it is necessary to identify both the “mainstream” of party ideology within any given period, as well as the ideological divisions that exist within the parties. This is a messy business, because as we will see, ideology can often be in conflict with interests. For instance, many Democrats opposed President Obama’s climate change initiative for reasons that had nothing to do with ideology, and a great deal to do with the fact that they came from energy producing states. To understand the role of party ideology—beliefs about what kinds of policies and laws should guide political life—we have to understand that American political parties tend to be ideologically divided.

III. The First Party System: Federalists, Jeffersonian Republicans, and the Struggle to Define the USA↑

The differences between the Federalist Party and the “Jeffersonian Republicans” (sometimes referred to as the Democratic-Republicans)—the first parties in the United States—originated in conflicting beliefs about the meaning and goals of the Constitution, differing regional economic interests, and the differing political cultures of the states. The Federalists—usually associated with the figure of Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of state—believed that the Constitution allowed the American national government to pursue a vigorous policy of national economic development in order to increase the fiscal capacity of the state, improve the economic infrastructure of the nation, and promote American manufacturing through protectionist trade policy. The policy agenda of the Federalists depended upon a broad understanding of the powers of the national government. Not surprisingly, the Federalists received most of their support from states along the North Eastern seaboard, the states where manufacturing played a significant role in the economy.

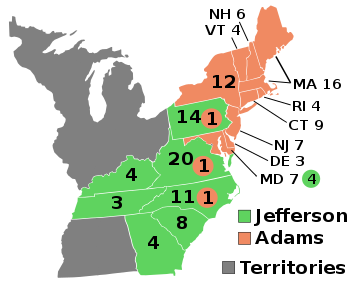

Figure 4.1: Electoral College Vote 1796

The Democratic-Republican Party—sometimes referred to as the “Jeffersonian Republicans,” the Democratic-Republicans, the Jeffersonian Democrats, or simply the “Jeffersonians”—coalesced around a different set of ideas and a different set of interests. Whereas the most able Federalist leaders and thinkers envisioned a future for the country based upon technological development and industrialization, those who formed the Democratic Republican party hoped to shape the economic and political future of the nation by promoting westward expansion and agricultural development. In addition, the Democratic-Republicans were suspicious of the power of the national government, and were particularly aghast at the financial policies promulgated by the Federalists. Their suspicions went much further: the devotees of Jefferson and Madison thought that the Federalists harbored crypto-monarchists who wished to subvert the democratic elements of the American constitution, consolidate power in the national government, and establish an aristocratic order in the new world.7 Thus, the Democratic Republicans did not see the Federalists as legitimate political opponents—they saw them as subversives who had to be completely defeated, so as to maintain the integrity of the Republic8.

This was not a peculiar trait of the Jeffersonians. During the 1790s, the American public and its leaders did not regard parties and partisanship as necessary elements of democratic politics. The Federalists did not merely think that the Democratic Republicans were unwise– they thought the Constitutional visions adopted by their opponents were completely erroneous, if not “un-American.” Federalist opposition to the Democratic Republicans contained a strong element of cultural disdain, as the Federalist bastions in the north east of the nation were not only the economic powerhouses of the nation, but also the most religious and “culturally conservative” regions in the country. Jefferson himself was renowned as a free thinker with unorthodox religious ideas, and his political compatriots had expressed sympathy if not support for the markedly anti-Christian French Revolution. Thus, while the Democratic Republicans thought their opponents anti-democratic monarchists who wished to establish an aristocratic social order, the Federalists thought their opponents were economically backward, violence prone levellers who wished to bring the degeneracy and immorality of the French revolution to the new world.

In order to wage political warfare against their opponents, however, both the Federalists and Democratic Republicans had to develop the rudiments of party organization, organizations without which it was impossible to put their political ideas into practice. The development of party organizations during this period illustrates an interesting paradox, however: parties emerged in order to make the constitutional order workable, yet as they developed, they would render some parts of the original system largely inoperative.

Party organizations developed in order to overcome the very practical problems imposed by geography, in an age when communicating and travelling over long distances was difficult. The basic task of any politician in a democratic society is to achieve support amongst the electorate. In the case of state and local elections during the late 18th century, this was a relatively straightforward task, as the number of voting citizens was relatively small. In the typical case, a group of “local notables” would meet in private to discuss their preferred candidates; nominations for office would occur at town meetings; disgruntled office-seekers could still seek out office on their own, if they felt that they had been unjustly excluded by the local power structure. Politics in such a setting, while certainly rambunctious, violent, and even routinely corrupt, was largely “non-partisan” Individuals contest with each other as individuals, and what we would call ideological differences are mostly absent. Political parties developed at the state level out of the need to select candidates for state-wide office, in particular, the offices created by the Constitution—such as Senators and members of the House of Representatives. Whereas selecting candidates for local elections could occur in local meetings, it was practically impossible to assemble large groups of citizens for “nominating conventions” given the difficulties of travelling during this time.9 Yet a solution presented itself—the state legislators, already assembled in the capitol, would select a list of candidates for the general election; each faction or party, having created its own list, would rely on committees of supporters throughout the state to support its favoured candidates. Thus emerged political parties in embryonic form.10

The role played by state level parties in selecting candidates for federal election was not at odds with the Constitutional order—the problem would emerge when Congressional party caucuses began playing a role in the selection of Presidential candidates. The first Presidential election was not controversial or even contested, as all political factions (and practically every citizen in the nation) supported George Washington as the obvious choice for President. Things changed once Washington was no longer available as a symbol of national unity. Despite the warnings of the outgoing President about the dangers of parties and partisanship, the elections of 1796 and 1800 exhibited fierce and even violent political conflict, conflict that would leave its mark upon the system of Presidential selection. Partisanship eliminated the independent role of the electoral college, before the system of Presidential selection even had an opportunity to be tested in practice.

In the original constitutional order, states played the primary role in determining how to select electors in the electoral college. State legislatures could choose the electors, or they could allow the electors to be chosen by voters; electors could be assigned to differing candidates on the basis of proportional representation (or on a district by district basis), or on the basis of a “general ticket,” in which the winning candidate would receive all of the electoral college votes from the state.11 If we keep in mind that the Framers did not assume that there would be organized party competition—and if we keep in mind the limits of “national media coverage” during this time, not to mention the difficulties of political campaigning in an era without cars, trains, or railroads—we can see why the electoral college needed a second stage: these series of state wide contests were unlikely to give a majority of votes to any single candidate12. In the event of a tie, or if no candidate achieves a majority, the Constitution gives the House of Representatives the responsibility for choosing the winner (in the latter case, the House must choose from the top five candidates.) However, the members of the House do not vote as individuals; each state casts one vote as a delegation, based upon the choice of the majority of its representatives, an arrangement which gives a decisive advantage to the smaller states at this stage of the selection process.

The early political parties, organized around national leaders, “hacked” the Constitution’s system for Presidential selection by adopting the practices used by state legislators—members of Congress promulgated lists of dedicated electors, who were then endorsed and supported by fellow partisans at the state level. Thus, rather than serving as an independent body that would choose amongst Presidential candidates based upon their own deliberations and determinations, the electors were instead committed to the specific candidates selected by the congressional caucuses of the Federalists and the Republicans. Without the unifying figure of General Washington, the Presidency became ensnared in American partisanship.13

Yet just as quickly as partisanship had emerged, it seemed to disappear, as the Jeffersonian Republicans routed the Federalists. For close to a quarter century, the USA became (almost) a one party state.

To what extent is the triumph of one political party a consequence of underlying socio-economic-demographic- geographical-technological factors, and to what extent is it dependent upon human action and choice—to adopt one policy rather than another, to succeed in one venture while failing in another? As we will see, there is no way to give a definitive answer to this question—the rise and fall of parties in American politics is determined by the decisions, successes, and failures of political leaders, as well as by social and economic changes that seem beyond the reach of control or even prediction.

We can see this by considering the fate of the Federalist Party, which was weakened after the election of 1800, and very soon faded into almost complete irrelevance as an organized political party.14 Was the Federalist Party doomed by demographics? One could easily make this case. The Federalists had most of their support in the North East, which was economically more developed but less populated than the South. Yet it is impossible to explain why the Federalists failed politically, without taking into account their political beliefs, their political strategies, and the contingent events that made their political objectives difficult to achieve.

All political parties are motivated by a mixture of ideas and interests, and the Federalists were no different— Hamilton and his allies thought Federalists policies would achieve both the public good, establish the validity of their understanding of the Constitution and their vision of political economy, and insure continuing control of the national government for Federalists. Their general political strategy was to build a coalition rooted in government patronage, financial reform, and economic development. Patronage was not used to create mass support for the Federalists amongst large groups of citizens willing to sell their votes for jobs, income, or subsidies. Rather, patronage was used to create a network of elites who would be bound to the national government and the Federalists, and who would use their local power and reputation to mobilize support for the Federalists. Distributing resources in order to create and support political allies would, of course, be a recurring theme of American politics. Even political leaders who have a genuine attachment to the common good must take into account the means necessary to mobilize public support for their policies—and patronage, in all of its various manifestations, is always an attractive method for mobilizing supporters.15

Just as importantly, the Federalists hoped to insure their political success by insuring the economic success of the nation, and this they pursued through a series of interconnected financial and economic reforms. The central plank of the Federalist economic platform was the assumption of state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War, a policy which was expected to have a number of positive benefits. By insuring that the state debts were not repudiated, the Federalists assured financial elites of the economic trustworthiness of the new nation; by paying interest on the debts (instead of simply retiring the debt) the Federalists would give financial elites additional reason to support the national government; by freeing states from their financial obligations, the Federalists would allow those states to reduce the tax burden on their own citizens, thereby insuring more investment, consumption, and economic growth. To finance the debt, federal taxes would be laid on foreign imports—an indirect tax that would be less observable, and thus less keenly felt, by most citizens. Further Federalist policies in public finance—in particular, the creation of a national bank—were also expected to promote economic growth and prosperity.

Federalist ideology extended to the realm of foreign and military affairs as well. During the 1790s, the world was shaken by the French Revolution, and all of the violent reform and violent conflict it precipitated. Most Americans, even most Federalists, were initially enthusiastic about the French revolution, yet this began to change as more Americans became aware of the radical character of the Jacobins and their allies. In particular, the clergy of the United States were revolted by the anti-Christian and atheistic tendencies of the French revolutionaries, and this helped the Federalists gain another political foothold. The followers of Jefferson remained committed to the revolutionary cause, and thought that the fall of the old regimes of Europe would initiate an era of peace and commercial prosperity. The Federalists looked at the outbreak of war in Europe not as a movement towards perpetual peace, but rather as a sign of the ever present danger of war and conflict; they did not directly support any side in the conflict, but they did think it provided additional reasons to support an American military establishment—an establishment necessary for defence against external and domestic enemies.

The main Federalist policies—strategic use of patronage to establish a network of like-minded elites, financial and economic reform, and a “realistic” foreign policy that did not elevate sympathy for foreign revolutionaries above the national interest—were successful enough to help the Federalists maintain control of the Presidency, and of the national government as a whole. Yet the limits of the Federalist strategy were also apparent, as their policies began to drive many citizens towards the Jeffersonians, particularly in the West and the South. Settlers in the western territories felt that the national government had not done enough to “pacify” Native American nations, particularly in what was then the southwest of the nation. Western settlers also felt that federal land policies had privileged large investors over ordinary citizens; the settlers also believed that federal trade policy had focussed on the interests of the North East, while neglecting the interest of the farmers who needed access to the Mississippi and the port of New Orleans. In addition, Federalist taxation policies were often deeply resented by rural farmers and western settlers—and this resentment often boiled over into resistance and outright rebellion.16 Thus, even while Federalist policies seemed to be successful in promoting economic development, citizens on the periphery of the nation were beginning to show signs of discontent.

One should note that the differences between Federalists and Republicans cannot be understood in “class” terms, if by class we mean “differences in income and wealth.” Different kinds of economic interests—not simply the differences in between the wealthy and the poor—led to different patterns of support. The typical wealthy Jeffersonian Republican was a southern land-owner—and usually a slave-owner as well. Such an individual might have little in common with a poor settler in rural western Pennsylvania, but both were suspicious of the Federalist platform, particularly the financial policies that benefited wealthy speculators and eastern bankers.

It would be a mistake to think that patterns of party support can be explained solely by economic interests, even if that explanation takes into account the complex nature of regional economic interests. Culture played an important role as well, though it is impossible to disentangle the “causal role” played by cultural and economic interests, as the fault lines of culture and economics so often coincided. The Federalists, in addition to representing the economic interests of the north east, particularly those engaged in commercial trade and finance, also found support amongst the cultural establishment: the mainstream churches, the large universities, and the established families. While the Federalists rejected the claim that they were aristocrats who were entitled to rule by birth, education, and virtue, they were nevertheless the more in-egalitarian of the parties, and Federalist elites never doubted that they were superior to the frontier farmers and small entrepreneurs within the Jeffersonian ranks who lacked education, manners, and wealth. Historians have noted that the contempt shown by Federalists for “the middling elements” of society contributed to the ferocity of anti-Federalist sentiment. Economic interests combined with the sense that their enemies were part of a different (and outmoded) social order to give the Republican Party an ever growing sense of unity.17

The Federalist response to relations with revolutionary France played an important role in sealing their electoral fate. As noted above, many Americans were initially sympathetic the Revolutionary cause, but this had changed by the mid-1790s. Federalist elites had long been averse to the radicalism and violence of the revolutionaries, but ordinary Americans were also disgusted the French Directorate’s attempts to interfere in American politics and interfere with American trade. Within the course of a few short years, people who had once applauded pro-revolutionary plays and newspapers and criticized the pro-British foreign policy of the Washington administration began to repudiate the French. The Federalists did not change the mind of men like Thomas Jefferson, but they appeared to have the public on their side, well into John Adams’ Presidency. All of this changed very quickly.

The failure of the Federalists to capitalize on anti-French sentiment provides an excellent lesson in how short-term political decisions can shape the outcomes of elections and the fate of political parties. Fearful that recent immigrants—particularly Irish immigrants– might have sympathy for revolutionary France, the Federalists passed a series of acts which made naturalization of immigrants much more onerous, and gave the executive branch a much freer hand in detaining and deporting resident aliens. Even more ominously, the Federalists attempted to restrain individuals from publicly expressing supposedly seditious, pro-French sentiment. This was bound to raise political passions, because the “press,” though not yet circulating widely amongst the mass of citizens, was nevertheless crucial to the diffusion of information and opinion amongst elites—and the press, more so than even today, was explicitly partisan. Writers, editors, and publishers made no effort to hide their support for either the Federalists or the Republicans—though the Jeffersonian press was more extensive, and with some notable exceptions, more inflammatory than Federalist journals. The Sedition Act, passed in the face of Republican opposition, was used by the Federalists against Republican critics. In addition to suppressing dissent, the Federalists initiated plans to develop and expand the military, not only to confront any threat from Revolutionary France, but also to suppress dissent and insurrection in the United States.

The Federalist Party did not entirely disappear after the election of 1800; it lingered on for decades in a much weakened form. The crushing defeat and the long, slow death that followed provides an excellent example how ideas shape political action, even when acting on those ideas comes with a heavy political cost. Rather than adjust to the democratic-libertarian ethos that was clearly coming to dominate the nation, the Federalists maintained their commitment to state-directed economic development, an aggressive anti-French foreign policy, and authoritarian security policies. Given the patterns of immigration, settlement, and population growth, the Federalist program appeared fated to fail. Yet had the party of Hamilton not overplayed its hand in response to the French Revolution and the threat of foreign radicals, the triumph of the Jeffersonians would probably not have been so complete or so long lasting.

After losing the 1800 Presidential election, the Federalist Party faded into relative insignificance in the national electoral arena.18 The period between 1800 and 1824 was dominated by the Jeffersonian Republicans—it even appeared as if the United States would not be characterized by party competition, as opposed to competition between differing regions and differing individuals. Such a system—a system without organized, permanent, and disciplined organization—appears to be most commensurable with the political order envisioned by Madison in Federalist Paper #10. Despite the absence of parties, however, politics did not disappear. Conflicts between regions, and conflicts between party elites and political outsiders, would eventually lead to the re-emergence of new political parties.

Initially, the Jeffersonian Republicans repudiated the “statism” of the Federalists: they eliminated many internal taxes, they eliminated the national government’s debts, they allowed the charter of the Bank of the United States to expire, and, in general, reduced the presence of the national government in the life of the nation. Yet overtime, the followers of Jefferson (and even Jefferson himself) synthesized Republicanism and Federalism. Jefferson’s decision to pursue the “Louisiana Purchase”—an essential part of the expansionary program necessary to advance the interests of the western farmers—depended upon a “loose construction” of the powers of the President in foreign affairs; the disasters of the War of 1812 led Jefferson’s followers to pursue national development, internal improvements, and even economic protectionism— though the Jeffersonian Republicans always claimed that they pursued these Federalist priorities within the boundaries established by the Constitution. Thus, the Jeffersonian Republicans not only defeated the Federalists; they ended up incorporating many Federalist ideas and policies as well.

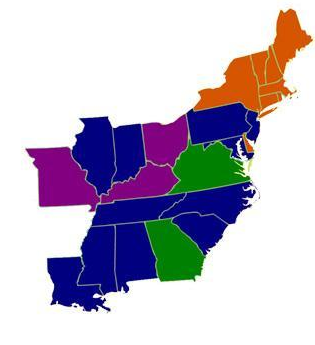

By 1824, the dominance of the Jeffersonian Republicans started to unravel, as the system of Presidential selection that had developed since 1800 began to be at odds with the emerging democratic ethos of American citizens. The problem was that, in the absence of a party system that could narrow the scope of electoral choice, the electoral college produced split decisions that, according to the Constitution, had to be resolved by the House of Representatives. In the 1824 election, the candidates were not distinguished by party affiliation or even by ideology, but rather by region and personality—Crawford from New York, Henry Clay from the West, John Calhoun from South Carolina, former Federalist from Massachusetts John Q. Adams, and the political outsider and war-hero, Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. Though Jackson received the most votes in the electoral college, he did not receive a majority of the total number of electoral votes. The House of Representatives—following the procedures outlined in the Constitution—chose to select John Quincy Adams from amongst the top five candidates. Andrew Jackson would return to win the next Presidential election in 1828—and in doing so, he would usher in a new party system.

Figure 4.2: 1824 Electoral College Vote

| Andrew Jackson | 99 | |

| Henry Clay | 37 | |

| John Quincy Adams | 84 | |

| William H. Crawford | 41 |

IV. The Second Party System: Whigs vs. Democrats↑

The period between 1828 and 1854 witnessed the birth of the American party system, and the birth of two of the most enduring political parties in the world—the Democratic Party (at the beginning) and the Republican Party (towards the end.) Over the course of little more than a decade, the United States went from being a nation where party competition was dying, to a nation where parties and party competition were key elements of the political order and even the culture. How did this occur?

Any explanation has to begin with President Andrew Jackson, and the concept of “Jacksonian Democracy.” Whatever the ideology of the Jeffersonian Republicans, in practice, the period between 1800 and 1824 was characterized by elite domination of political life and a relatively restricted role for public participation. Andrew Jackson’s political career demolished some elements of aristocratic entitlement19 and popular deference in American politics— his path to the Presidency was enabled by the expanding number of white, male citizens who were beginning to make their power felt in the electoral arena.

Figure 4.3: 1828 Electoral College Vote

| Andrew Jackson (Democrat) | 178 | |

| John Quincy Adams (National Republican) | 83 |

As in the case of the “critical election” of 180020, the Presidential election of 1828 revealed clear regional divisions in the country—and in fact, the regional bases of party support and the policy questions that differentiated the parties were largely unchanged, even though the party names had altered. Jackson received overwhelming support in the South and the West, though he was also able to eke out more narrow victories in Pennsylvania and New York. John Quincy Adams won his electoral victories in former strongholds of the Federalist Party (such as New England and Delaware), and his policies were more Hamiltonian than Jeffersonian; the son of the Federalist John Adams ran on a platform of internal improvements and support for the national bank. Jackson inherited the Jeffersonian ideas of strict constitutional construction, opposition to the national bank, and support for westward expansion. The election results suggested that John Quincy Adams’ attempt to resurrect Federalist ideas was doomed; unlike the aftermath of 1800, however, the 1828 election did not give rise to a period of one-party dominance, but instead gave rise to an era in which party competition became an accepted part of the American order.

One of Andrew Jackson’s supporters provided the initial intellectual support for the party system. Martin Van Buren, a major figure in New York state politics who had a keen sense for the direction of popular sentiment, threw his support behind Andrew Jackson after the general’s near victory in 1824, and helped to re-articulate the “Jeffersonian” political principles that would eventually shape Jackson’s Presidency. Under Van Buren’s tutelage, Jackson repudiated the “federalist tendencies” that he had shown as Senator, and helped to develop the core commitments that would define the Democratic Party for close to a century. In contrast with Jefferson, however, Van Buren would also explain why partisanship and party competition were essential to representative government, and not just a temporary aberration. In New York state, Van Buren had been an early master of party organization, and according to some commentators, he embodied the kind of political operator who was motivated by the lure of office and power as opposed to the appeal of ideas. Whether or not this is true—and I think it somewhat unfair to Van Buren—it is the case that Van Buren explained why party competition and partisanship were compatible with American constitutionalism. The conflict between the Federalists and the Jeffersonians had been a conflict between truly “great” parties—great in the sense that these groups embodied fundamentally distinct and incompatible understandings of the Constitution. Federalists such as Hamilton had to be defeated, defeated completely, because they adhered to anti-democratic ideas that were fundamentally incompatible with Constitutional system. In essence, Van Buren accused Hamilton and his adherents of being closeted monarchists who hoped to create an aristocratic social order, a moneyed financial elite, and an imperialistic state along the lines of European autocrats. Such people had to be defeated. Yet not all party differences rose to the level of principle. Having established the proper understanding of the Constitutional order, party politics could be reconceived as a useful form of elite competition, in which differing groups of candidates could appeal to the public on the basis of policy differences—and even personal differences rooted in character and competence—that did not rise to the level of fundamental political principles. Having mastered the basic techniques of mass mobilization in New York, Van Buren was able to foresee that political conflict could emerge even without deep differences in political philosophy, and that this kind of political conflict could benefit the public as a whole. Van Buren did not directly create the party system, but he was able to foresee that party conflict—kept within the boundaries established by the Constitution and, perhaps, American political culture as a whole—would become a normal part of the American political experience.21

There is some disagreement over whether the main parties that developed during the mid-19th century—the Democrats and the Whigs—even had distinctive approaches to public policy, let alone political philosophy.22 Some scholars have argued that the Jacksonian Democrats were motivated by nothing more than the desire for power and the spoils of office, at least initially. Over time, however, some relatively clear distinctions between the parties emerged. The Democratic Party, the party of Jackson, were more likely to oppose loose construction of Constitutional powers, particularly if that involved the national government in complicated and expensive projects; they tended to adopt the Jeffersonian conception of political economy, a vision in which small farmers would play more of a role than financiers and industrialists. The Whigs were more “Hamiltonian” in orientation—they tended to support a policy of internal improvements and economic protectionism, though they would always reject the claim that they were re-born Federalists. On issues like internal improvement and economic protectionism, the Jacksonian Democrats were often willing to adopt “Hamiltonian” positions, something that was necessary for them to maintain support in New York, Pennsylvania, and new states such as Kentucky and Ohio (states that benefited from spending on internal improvements such as roads and canals.)

On the issue of the national bank, however, the differences between the parties were quite stark. Like the Federalists, the Whigs were often accused of being the servants of financial interests; and the followers of Jackson in the Democratic Party distinguished themselves by opposing government’s role in creating and maintaining banking institutions. The issue had taken on greater salience given the deep economic recession of 1819, a crisis that had imprinted itself upon the public mind and shaped political consciousness in the Jacksonian Era. Over time, an even broader array of issues would come to separate the Whig and Democratic party, as the Democrats adopted a more aggressive attitude towards national expansion, the removal of Native Americans, and war with Mexico. Thus, the differences between the Whigs and Democrats were significant, though certainly not as extensive as the differences that characterize party ideology in the 21st century.

To fight for their principles, and to fight for the spoils of power, the Whigs and the Democrats would develop new forms of party organization that would allow them to attract cadres of political activists, select candidates, and mobilize voters. Prior to the Jacksonian era, “party organization” in American national politics was rooted in the Congressional Caucus—or “King Caucus,” as its detractors referred to it. This system, in which elected members of Congress attempted to narrow the electoral playing field by endorsing a particular Presidential candidate, had been shown to be inadequate by 1824. Rather than lining up behind the candidate endorsed by the Congressional Caucus in Washington, state legislators and state conventions endorsed a variety of candidates, all of them claiming to represent the “Democratic Republican” party of Jefferson. Out of the chaos of the 1824 election, new types of party organization developed along with new institutions for performing the fundamental tasks of electoral politics—choosing candidates and mobilizing supporters.

Whereas the “Jeffersonian Republicans” and “Federalists” were to a considerable extent just names for groups of like-minded elites, the Democratic Party and Whig Party were actual mass organizations, made up of cadres of political activists who were distinct from both elected elites and the general public. In an era with limited mass communication, political campaigning was labour intensive—it depended upon the work of thousands of “volunteers,” who would do the work of mobilizing voters. Party supporters volunteered their labour in the hopes of receiving some kind of material benefit—access to government jobs and access to government contracts being the most sought after prizes. Thus, the “spoils system” became an integral part of American party politics.23

Party organization became much more complex in this period, but it also became much more decentralized—rather than being dominated by coteries of national elites, national elites became the creatures of state and local party organizations, and most importantly, nominations for elections occurred through state and local nominating conventions. In the convention system, party organizations conducted meetings or conventions which produced official slates of candidates for all elected offices–in contrast with the previous systems of candidate selection which was simultaneously more “top down” (due to the role of the Congressional Caucus) and more individualistic (in regards to lower level offices, in particular; as the election of 1824 illustrates, disgruntled aspirants to higher office could chose to simply ignore the dictates of the Congressional caucus and run on their own.) State party conventions would select candidates for state-wide office; district conventions would select candidates for the House of Representatives; delegates to these conventions were chosen by local party associations. A fully national convention system developed by the end of Andrew Jackson’s second term. This was a pyramid-like selection process which began with local meetings, moved through the state level, and culminated in a national party meeting which selected the candidates for President and Vice-President. Combined with the development of party regulars motivated by the spoils of office, the convention provided a link between political offices from the lowest state official to the Presidency. The development of the party convention was sporadic—eastern states, particularly New York and Pennsylvania, were the first adopters of this mode of candidate selection–but it gradually spread from east to west, and from the Democratic Party to the Whig Party. By the election of 1840, the convention system joined the spoils system as a key element in party organization.

In contrast with the system of “elite selection” that had characterized candidate selection in the first few decades of the 19th century, the convention system for candidate selection appeared to be more open to popular influence. In practice, however, party conventions were dominated by party regulars and office holders; the general public played no direct role in the selection of candidates, though of course the parties did their best to discern which candidates were likely to generate popular enthusiasm. Having selected candidates, party organizations would attempt to mobilize the voters through the art of public spectacle—mass parades and mass public meetings enraptured the voters, with chanting, singing, and celebrating playing more of a role than calm deliberation. European visitors who expected American democracy to resemble the Roman Senate were severely disappointed— American mass democracy was disorderly and carnivalesque, at least on the surface. Beneath the apparent disorder, party organizations had developed ways to mobilize supporters, select candidates, develop platforms, and engage the public.

During the second party system, in contrast to party conflict during our own time, both of the major parties were competitive in most regions of the nation. We can see this by considering the regional representation of parties in the House of Representatives in 1836 and 1848.

Table 4.2: Geographic Divisions of The 1836 and 1848 Elections, House of Representatives, by Region

The South

| Democrats | Whigs | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 3/5 | 2/2 | |

| Arkansas | 1/1 | 0 | |

| Florida | /0 | /1 | |

| Georgia | 8/4 | 1/4 | |

| Louisiana | 1/3 | 2/1 | |

| Mississippi | 2/4 | 0/0 | |

| North Carolina | 5/3 | 8/6 | |

| Tennessee | 3/7 | 10/4 | |

| South Carolina | 2/7 | 1/0 | 6 (Nullifier)/0 |

| Virginia | 15/13 | 6/2 | |

| % Total Seats | 40 | 30 |

Mid-Atlantic States

| Democrats | Whigs | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 6/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 (Free Soil) |

| Delaware | 0/0 | 1/1 | |

| Maryland | 4/3 | 4/3 | |

| New Jersey | 0/1 | 6/4 | |

| New York | 30/1 | 10/32 | 0/1 (Free Soil) |

| Pennsylvania | 18/9 | 3/13 | 7/1 (Free Soil) |

| TOTAL | 58/ | 24/ | 7/ |

New England

| Democrats | Whigs | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maine | 6/5 | 2/2 | |

| Massachusetts | 2/0 | 10/8 | /1 (Free Soil) |

| New Hampshire | 5/2 | 0/1 | /1 |

| Rhode Island | 0/0 | 2/2 | |

| Vermont | 1/1 | 4/3 | |

| TOTAL | 14 | 18 |

Middle West

| Democrats | Whigs | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illinois | 3/6 | 0/1 | |

| Indiana | 1/8 | 6/1 | 0/1 (Free Soil) |

| Iowa | /2 | /0 | |

| Kentucky | 1/4 | 11/6 | |

| Michigan | 1/2 | 0/1 | |

| Missouri | 2/0 | 0/5 | |

| Ohio | 8/11 | 11/8 | 0/2 (Free Soil) |

| Wisconsin | /1 | /1 | /1 (Free Soil) |

| TOTAL | 16 | 28 |

Table 4.3 Parties in the House of Representatives, 1828-1850

| Democrats | Whigs | Anti-Masonic | Nullifier | Free Soil | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1828 | 136 | 72 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1830 | 126 | 66 | 17 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1832 | 143 | 63 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 1834 | 143 | 75 | 16 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1836 | 128 | 100 | 16 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1838 | 125 | 109 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1840 | 99 | 142 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1842 | 148 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 1844 | 142 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 1846 | 112 | 116 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1848 | 113 | 108 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| 1850 | 130 | 86 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 |

Voting in the electoral college between 1836 and 1848 also reveals a similar pattern—both parties were competitive in most regions and most states, though there were some states that were consistently in the Whig or Democratic camp. This is compatible with the claim that, during this period, the parties had relatively minimal policy disagreements, competing instead on the basis of idiosyncratic personal appeals.24 But we should note that the absence of major ideological differences between the main parties does not mean that there were not serious political divisions within the country as a whole. The question of slavery, particularly the power of the national government to limit the growth of slavery in the south west, divided the country into two ideological camps. Yet these were divisions that split both parties in two as well.

The problem of slavery in the 19th century was rooted in the Constitution’s compromises with the “peculiar institution.” The Constitution’s relationship to slavery reflects the peculiar situation of the Founders—while some Founders clearly recognized the injustice of slavery, they knew that it would be impossible (or at least difficult) to challenge slavery without threatening the project of constitutional reform. Furthermore, the southern states—the states where slave labour played a large role in the economy—demanded protection for slavery and the slave trade, at least in the short term. By 1807, as soon as the Constitution allowed it, Congress passed an act prohibiting the importation of slavery. Yet any hope that this might put slavery on the course of extinction proved to be illusory.

Slavery proved to be an enduring part of the Southern political economy and southern political culture, contrary to the expectation of the Founding generation. Southern political leaders, whether Whig or Democrat, tended to think that the future of their region depended upon extending the slave economy to the West25, and preventing federal intervention into the institution of slavery wherever it existed. The economic and political interests of the North were not nearly as uniform. The number of people voicing moral objections to slavery grew over the course of the 19th century; many more argued that slave labour necessarily undermined the value of free labour. Yet the Northern states also benefitted from their economic relations with the slave states, and both parties were aware that any attempt to adopt an anti-slavery platform would lose them far more votes in the South than they would gain in the North. From the perspective of pure political calculation, neither party had anything to gain from adopting either a strict anti-slavery or pro-slavery position, and thus both parties ended up with pro and anti-slavery wings. The most serious political disagreements existed within each party.

The ability of the parties to keep slavery off the “electoral agenda” depended upon several compromises over the status of slavery in the Western territories and the maintenance of slavery in the South. Most important was the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which emerged out of controversies over the admission of Missouri to the Union. James Tallmadge of New York added an amendment to the bill admitting Missouri to the Union which made (partial) slave emancipation a condition for admission. The Southern states, by this point, were united in support of slavery, and regarded this proposal as a threat serious enough to spark violent conflict. The South was outvoted in the House of Representatives, but the regional balance of power was quite different in the Senate, where the vote on the Missouri Bill and the Tallmadge Amendment was deadlocked. Missouri’s admission as a slave state was eventually achieved by simultaneously admitting Maine as a free state, carved out of Massachusetts. By doing this, the balance of power in the Senate between slave and free states was maintained. But there was an additional compromise as well—all future states carved out of the Louisiana Territory that were north of 36 30 were to be admitted as free states. Political leaders in both parties and all regions hoped that the Missouri Compromise would maintain the balance between North and South for the indefinite future. The second party system was built upon the Missouri Compromise— had it failed, the Jeffersonian Republican Party would have split into two sectional parties. Instead of sectional parties, the second party system was characterized by national parties who were internally divided along sectional lines over the question of slavery. As the compromise came undone, so too did the party system.

Four major political events illustrate how the compromise over slavery broke down, leading to the end of the second party system and the demise of the Whig Party. The first major event was the Presidential election of 1844, an election which foreshadowed the ideological splintering of the nation. The Democratic Party ran on an expansionist or annexationist platform—in contrast with the Whigs, the Democrats promised to assert American control over territory that belonged to Mexico, territory in what is now the American South West. The Whigs selected Henry Clay as their candidate, the most articulate proponent of the Whig perspective on economic nationalism, internal improvements, banking, and many of the other issues that had divided the parties in the past. Despite his prominent political career and national reputation, the public rejected the “American System” of Clay and the Whigs, in favour of the Democratic Party’s vision of westward expansion and an economy rooted in agriculture and trade.

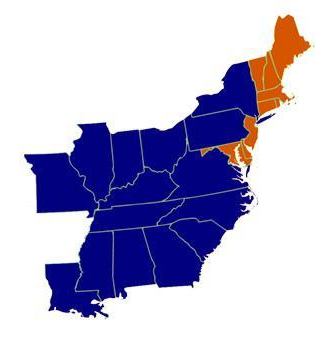

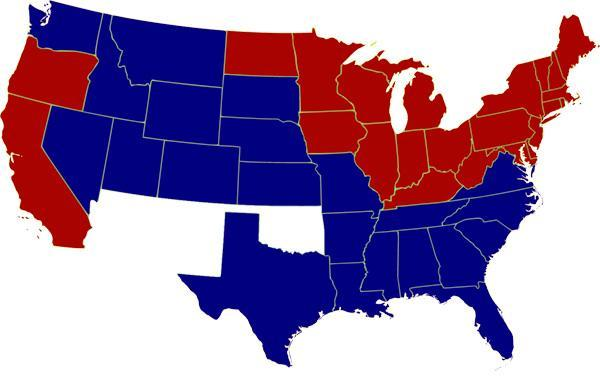

The election of 1844 illustrates several crucial dimensions of party competition in the United States. First, the national pattern of party competition was rooted in the complexity of regional economic interests. Consider the electoral college results from 1844 election:

Figure 4.4: 1844 Presidential Election

| Electoral College | Popular Vote | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| James Polk (Democrat) | 170 | 49.5 | |

| Henry Clay (Whig) | 105 | 48.1 | |

| James Birney (Liberty Party) | 0 | 2.3% |

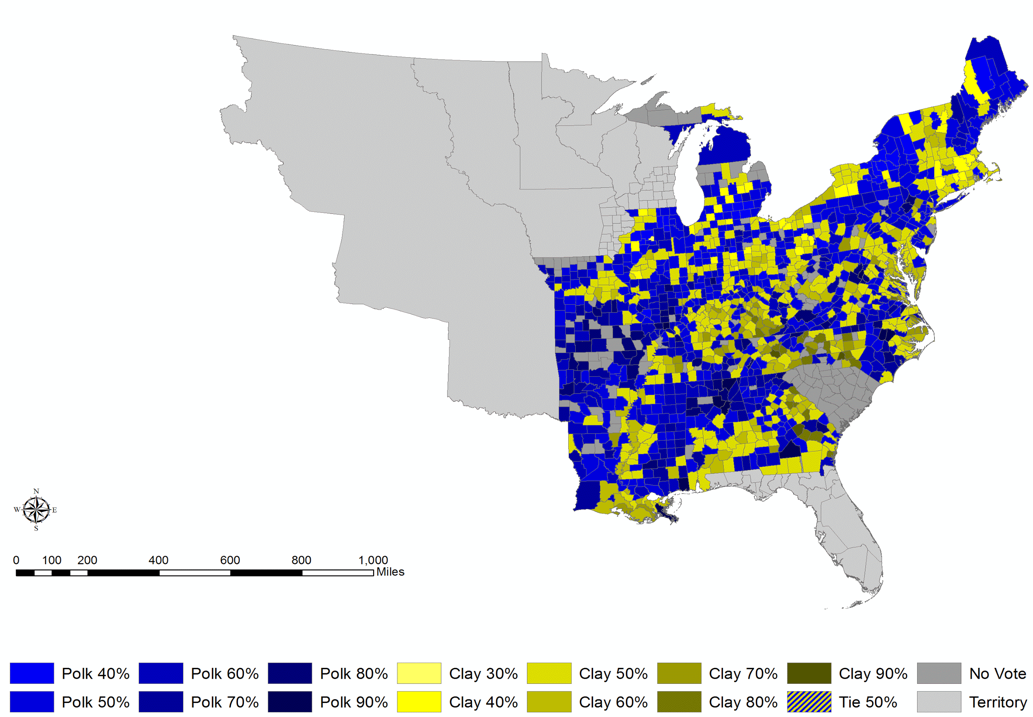

A quick look at this map might lead one to conclude that the pro-annexationist Democratic Party had a clear advantage in those states whose economic interest were most closely tied to westward expansion. Yet economic interests within the states were not uniform, as illustrated by this map of Presidential election results by county:

Figure 4.5: 1844 Presidential Election Results by County

The Whigs were able to compete with the Democrats in many counties in the South, not because of ideological differences over slavery, but because wealthy slave owners often concluded that western expansion would reduce the value of their property (due to increased competition.) In addition, during the course of the actual political campaign, Presidential candidates and party organizations often had to present slightly different messages to different regions of the country in order to maximize their competitiveness—in the South, for instance, Henry Clay often hedged his position of western annexation; in the North, Democrats hoping to appeal to anti-slavery voters continued to repeat Jefferson’s claim that territorial expansion would “diffuse” slavery through the west, making emancipation more likely to occur in the future.

In northern states like Pennsylvania, one might think that the Whig’s “American System” would have insured their success. Yet Democrats were able to appeal to the interests of new immigrants—Irish and German Catholics, for the most part— while the Whigs attempted to woo American Protestant workers who faced competition from immigrant laborers. Thus, the parties were able to compete in most regions of the country, not only because of the complexity of economic interests and the emergence of cultural and religious divisions amongst white voters, but also because the technology of communication, being relatively undeveloped, allowed the parties to tailor their message to specific regional audiences, without fearing that their inconsistencies would be revealed in national newspapers, or on the nightly news, Twitter, or You Tube.

Interlude: The Spatial Theory of Party Competition, Duverger’s Law, and the Role of Third Parties in American Political Development↑

The Presidential election of 1844 helps to illustrate “the spatial model of party competition” developed by the economist Anthony Downs. The key claim of the spatial model is that, in a two party system with a first past the post, winner take all electoral system, the two parties will tend to adopt relatively similar policy platforms. In other words, both parties, in making appeals to the public, will converge around the ideological center. We know that this is wrong as applied to the American political system today, but it is useful to think about why this model of partisan conflict is wrong.

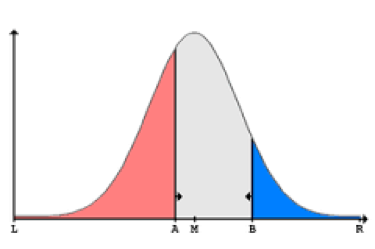

Figure 4.6: The Spatial Theory of Voting

| L= Left wing (e.g. egalitarian) position |

| R= right wing (e.g. individualist) position |

| M= Median voter |

| A= Ideological preferences of Party A |

| B= Ideological Preferences of Party B |

Assume first that ideology can be measured along a single “left versus right” dimension; this is a simplification, but it is a useful one. This one-dimensional view of ideology focuses solely on the role of the government in the economy– at the far left, you have complete state control of private property, at the far right, you have a libertarian night-watchman state. Next, let us assume that the distribution of ideology in the general public can be modelled as a bell curve; most people will cluster around the moderate middle, with relatively few anarchists and communists at the extremes.

Given this distribution of ideology in the public, how will parties respond in a “first past the post, winner take all” electoral system? If we assume that political parties are interested in winning elections, then we would predict that the parties will converge to the ideological centre, trying to capture as many votes amongst the moderate middle as possible; they will remain distinct, however, because if they become truly indistinguishable, then they will start to lose too many of the extremists’ votes. Now, we should note that this model does not even depend upon a ‘normal’ or “bell curve” shaped distribution of policy preferences in the general public– if parties want to win elections, they will converge on the centre even if public opinion is not normally distributed, at least in a first past the post system where third parties are not usually much of a threat. The main claim of the theory is this—if we assume that political elites are motivated primarily by their interest in achieving power, then we would expect that political parties (in a two party system, based upon first past the post elections) would converge on the ideological center; power seeking parties in a two party system will thus come to resemble one another, as moving to ideological extremes will decrease their chances of electoral victory.

The theory that power-obsessed parties will “converge on the center” can account for some aspects of American political development. As long ago as the early 19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that, in the American system, “great parties” do not exist; that is, parties that have fundamentally different principles about the proper arrangement of society. While Tocqueville observed that there were some differences between the parties on economic questions (as we have seen, the Whig party was more disposed towards the interests of finance and internal commercial and industrial development; the Democrats of the 19th century were more oriented towards agriculture and westward expansion) party competition was more like a sporting event than an ideological battle.

The spatial theory of party competition helps to explain why the United States developed a two party system in the nineteenth century. While some have suggested that there could be sociological reasons for the two party system, most scholars would argue that the two party system in the United States is best explained by American electoral institutions. According to the political scientist Maurice Duverger, electoral systems based upon a “first past the post, winner take all” electoral system will tend to generate two-party political competition, as opposed to a multi-party system.26 The reason for this is relatively simple. Imagine that you are a socialist in the United States today—would it be better for you to support a socialist party, or support the existing “left-leaning” Democratic Party? If we assume that approximately 10% of American voters are socialist, and if we also assume that they are more or less evenly distributed throughout the nation (though clustered in college towns), it would be difficult for the Socialist Party to win any seats in the House or the Senate, and impossible for the party to win the Presidency. Yet if the Socialist Party received 10% of the vote, it would in all likelihood be an electoral disaster for the Democratic Party– it makes one wonder why Republicans haven’t provided more seed money for socialist party formation. If we assume that most voters wish to avoid the “worst case” political scenario, however—electoral victory by the party that you most oppose— then we can see why most voters in a “winner take all, first past the post” systems will support one of two established parties. This tendency is known as “Duverger’s Law.”

Unlike laws in the physical sciences, however, Duverger’s Law has some very notable exceptions. “Duverger’s Law” and the spatial model both assume that electoral victory is always the most important goal of political actors, and that avoiding “the worst case scenario” is always the primary consideration of voters. The 1844 Presidential election illustrates why these assumptions are incorrect. Why does it matter that some voters are motivated by the desire to vote for a preferred party and a preferred ideology, as opposed to being motivated by the “rational” desire to avoid the worst case scenario? It matters because even a small number of “non-strategic” voters can shift the results in an election. While the Whigs and Democrats both operated, more or less, as if they were motivated by electoral victory, the Liberty Party—an anti-slavery party—ran a candidate in the Presidential, despite having no hope of victory. Yet by receiving over 2% of the vote, in an era of tight electoral competition, the Liberty Party almost certainly determined the outcome of the election by allowing the Democrats to win close electoral contests in Pennsylvania and New York. The Democrats would face a similar problem in 1848, when a third party candidate, former President Martin Van Buren, ran as the candidate for the “Free Soil” Party, winning close to 10% of the vote, many of whom were anti-slavery Democrats. So while both political parties behaved according to the spatial theory of party competition and Duverger’s Law/Tendency, they were vulnerable to third party candidates running on anti-slavery platforms. Both theories are based upon the premise that ideas never trump interests. Even if most politicians and most voters are motivated by interests, a small number of individuals motivated by political ideas can shift the political balance of power.

What allowed for one of these third parties—the Republican Party—to replace the Whigs? Two things had to occur—slavery had to become even more significant as an issue, and political changes had to make it more difficult for anti-slavery voters to stay within the Democratic Party. To explain why slavery became more significant as an issue, one would have to consider the cultural factors which shaped political consciousness in the free states of the USA. To explain why the Democratic Party was no longer able to appeal to anti-slavery voters, one would have to consider the consequences of the Mexican War, the Wilmot Proviso, the Kanas Nebraska Act, and the Dred Scott decision.